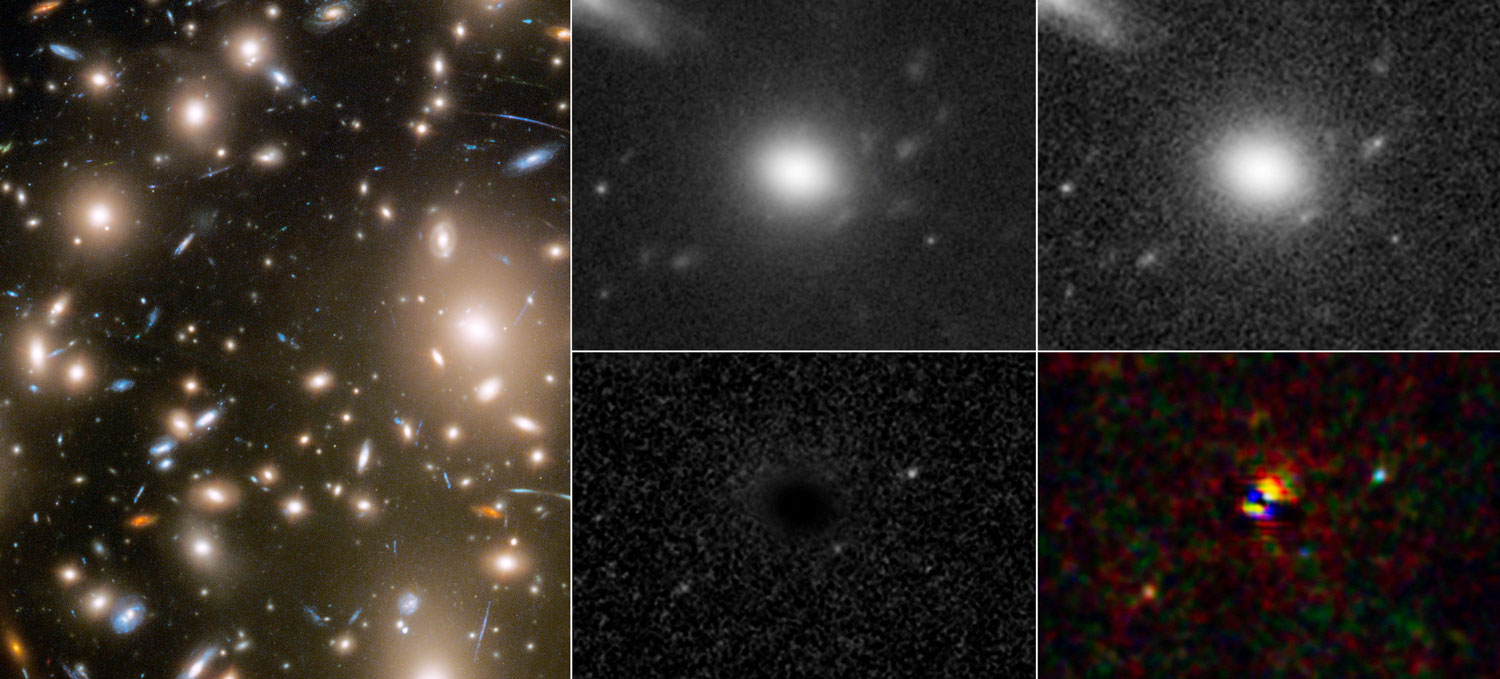

Since 1977, the US has spent at least US$16-billion to design, build and operate the Hubble Space Telescope. What a bargain. Not only has Hubble redefined how humans understand the universe, but it’s played a critical role in training a generation of scientists and engineers.

Unfortunately, Hubble is steadily losing altitude — essentially falling back to Earth — and soon Nasa will have to make a decision. It must either boost the telescope to a higher orbit, or let it continue falling until it crashes back to Earth, hopefully in the ocean.

The good news is that technology is emerging to save the Hubble, and Nasa is willing to work with companies to make a mission happen. The bad news is that Nasa will not pay for the effort. That’s the wrong call. If Nasa is serious about prolonging a national asset’s life, it should pay for it. Doing so will attract more and potentially better bidders and play a role in accelerating the development of the emerging satellite repair industry.

For at least a century, scientists speculated on what might be seen by a telescope situated beyond the distorting effects of Earth’s atmosphere. That dream became a funded reality in the 1970s, when Nasa authorised the development of the Hubble. From the start, it was designed to be repaired and serviced in space. Reparability came in handy, quickly: when Hubble launched in 1990, years late and wildly over-budget, it had a flaw in its mirror that rendered its images blurry.

Fortunately, what could have been a multibillion-dollar fiasco turned into a triumph. In 1993, Nasa launched the Space Shuttle on a mission to correct the Hubble’s optics. It worked, and over the next three decades the public has been gifted with Hubble’s photos and discoveries, while scientists have published more than 19 000 papers using Hubble data, cementing the US as the preeminent hub for astronomy and astrophysics. These discoveries have inspired new generations of students to enter science and engineering fields, furthering US scientific leadership.

Servicing

Maintaining those benefits has required maintaining the telescope. Four more servicing missions have been launched since that first fix, with the most recent in 2009. That was to be the last one because of the Space Shuttle retirement. But at least a few folks held out hope for another rescue.

Since at least the 1990s, public and private researchers have been working on technology to service and boost in-orbit satellites. For example, last month the US military selected Impulse Space, a start-up, to build an outer space refuelling depot for an in-orbit demonstration in 2025. Nasa has a refuelling project scheduled for launch no earlier than 2026.

The numbers of private companies seeking to accomplish other kinds of satellite servicing, from boosting orbits to mechanical repairs, are expanding rapidly. As of early 2022, there were at least 30 companies, globally. The advances are coming quick: in April, Lockheed Martin used two in-flight satellites to demonstrate its AI servicing algorithms and associated technologies.

Meanwhile, Hubble remains scientifically relevant, providing valuable observations of nearby stars, galaxies and black holes. It also complements the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, which can observe older, more distant objects that might be obscured by time and physical obstructions like dust.

Without intervention, Hubble should be able to keep doing its job into the latter part of this decade. After that, the prospects become hazy, in part due to its gradual but inevitable descent to Earth. In 2009, the Space Shuttle lifted Hubble to a safe 560km above the Earth; since then, it’s fallen to about 530km; Nasa told me it believes a boost would be possible as low as roughly 500km, an altitude it will reach around 2025 (science can continue into the 2030s). After that, Nasa’s options will be limited, and the telescope will likely burn up in the atmosphere, with the remaining fragments crashing into Earth.

Help could be on the way. In September, Nasa agreed to study whether it would be possible to boost — and possibly repair — the telescope using a spacecraft from Elon Musk’s SpaceX. A few months later, Nasa formally requested that other companies interested in “demonstrating commercial capabilities to re-boost the orbit of a satellite” send over proposals applicable to the Hubble. There’s just one catch: Nasa expects the mission to be performed on a “no-exchange-of-funds basis”. In other words: please fix our telescope for free.

Nasa didn’t respond when asked why it isn’t willing to pay to extend this asset. Perhaps, at a time of tight federal budgeting in the US, Nasa doesn’t want to tempt the budget cutters. But there’s another, more optimistic scenario: Nasa is betting that a Hubble repair mission is a priceless marketing opportunity for companies in the emerging satellite servicing sector. Why wouldn’t they do it for free?

The better path for Nasa, and the Hubble Space Telescope, is to offer to pay for a servicing mission

As of mid-May, Nasa had received eight responses to its request to re-boost Hubble for free. Of these, only one has been publicised. Astroscale US, a space junk removal and satellite servicing company, and Momentus, a provider of space services, propose to launch a robotic vehicle that will attach to Hubble, boost it 50km higher, and then clear any space junk out of the way of the new orbital path. If successful, it would mark the starting line for the next stage in the space economy. If it failed, questions might be asked as to why Nasa entrusted a national asset to the rescue efforts of volunteers.

The better path for Nasa, and the Hubble Space Telescope, is to offer to pay for a servicing mission. Doing so would likely incentivise more and potentially better proposals, and spur further innovation in the emerging satellite repair industry. How much to pay for such a mission is up to the US congress. But the fact that an instrument essential to American competitiveness is at stake requires that it be more than a token.

The Hubble was once the future of American science and engineering. Paying to save it ensures that it will continue to be so for decades to come. — Adam Minter, (c) 2023 Bloomberg LP