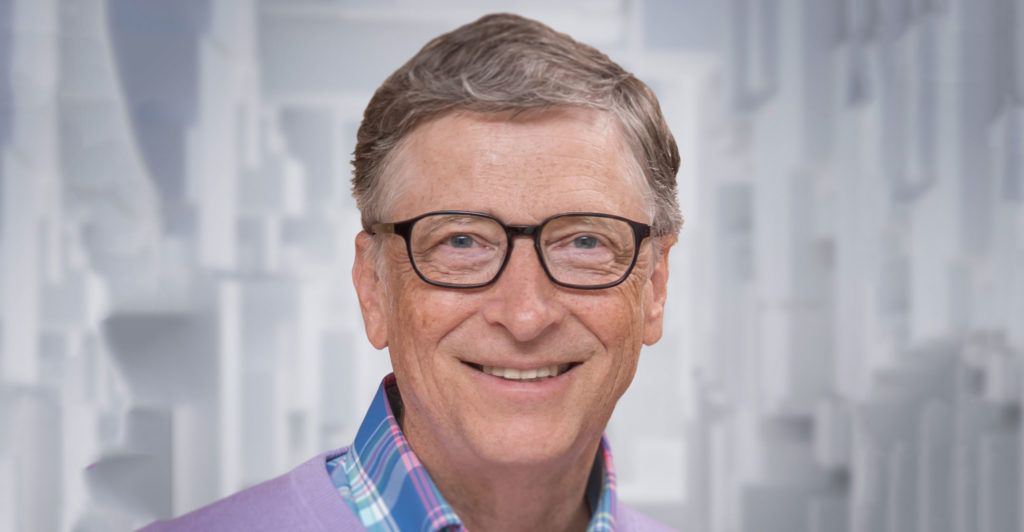

Bill Gates raised more than US$1-billion in corporate funding for Breakthrough Energy Catalyst, drawing on BlackRock’s Larry Fink and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella to rally support for some of the world’s most demanding clean-energy projects.

BlackRock is making a five-year, $100-million grant from its charitable foundation. Microsoft and the other backers — General Motors, Bank of America, American Airlines Group, Boston Consulting Group and ArcelorMittal — are providing a mix of equity capital and so-called offtakes, or purchase agreements tied to the projects.

“We’re not doing this to make money,” Fink, BlackRock’s CEO, said in an interview together with Gates on Bloomberg Television. “We’re doing this to seed these ideas, to rapidly accelerate ideas.”

Gates established Breakthrough Energy Catalyst to accelerate the commercial viability of four key solutions to the climate crisis: green hydrogen, sustainable aviation fuel, long-duration battery storage and carbon capture from the air. In practice, Catalyst will supply the cash needed to get capital-intensive projects off the ground, before debt financing and government funds can be raised to cover the remaining 90% of the cost.

Today, none of those four solutions is cheap enough to spur widespread adoption. For example, jet fuel derived from more sustainable sources such as industrial waste or alcohol is about five times as expensive as kerosene.

‘Green premium’

Ideally, the Catalyst projects will, by operating at scale, prove that the underlying technology can be cost-competitive and eliminate the “green premium” over conventional standards.

“The model here is what happened with wind and solar and lithium-ion,” Gates said. “Those products had very high prices compared to conventional techniques, and fortunately Germany and Japan and other buyers funded the scale-up, and now those products fit the normal sort of client-investing metrics.”

The difference now is speed. Governments that signed the Paris Agreement on climate in 2015 are racing to meet a mid-century goal of reaching net zero, which requires not only emissions cuts but also removing carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere.

The pathway for solar and wind, that was a 30-year pathway to make it competitive with hydrocarbons. We don’t have 30 years. We don’t have 10 years.

Nine of the world’s largest economies and many companies, including BlackRock, have pledged to reach that target.

“The pathway for solar and wind, that was a 30-year pathway to make it competitive with hydrocarbons,” Fink said. “We don’t have 30 years. We don’t have 10 years.”

Gates, who has estimated the cost of reaching net-zero emissions at $50-trillion, is hoping his programme becomes a model for public-private cooperation to address the threat of climate change.

‘Very serious conversations’

In August, Catalyst agreed to raise $1.5-billion in return for billions more in support, some of it contingent on legislation from the US department of energy. Separately, Catalyst committed $500-million in June in return for matching funds from the European Commission and European Investment Bank for a similar effort across the Atlantic.

Gates first pitched Nadella and then Fink, who said he in turn had some “very serious conversations” persuading fellow CEOs to back Catalyst. ArcelorMittal is making a $100-million equity investment over five years, and American Airlines also is contributing $100-million. The other partners didn’t detail their involvement.

Upfront expense and scalability are two major differences between most tech products and clean-energy solutions. While little to no capital may be required to develop a smartphone app, even a pilot project in carbon capture can cost tens of millions of dollars.

Also, large investors have mostly steered clear of ambitious green undertakings because of uncertain returns. Gates himself has noted publicly that he “lost a lot of money” on battery development.

Fink, who oversees almost $10-trillion in assets at BlackRock, said there’s an “enormous” amount of capital waiting to invest in technology proven to reduce the green premium.

“I’m not frightened about where the money’s coming from,” he said. “I just want to make sure that we have the science and technology and the viability. Once we know that, the capital will be there.”

Coinciding with the infusion of new cash and commitments, Catalyst is inviting would-be projects to fill out a request for information. That’ll be followed by a more precise and technical request for proposal, or RFP, possibly by the end of the year.

Gates, in the interview, laid out a timeline and some parameters:

- Catalyst will start funding projects in 2022, probably several in each area.

- Funding will cover early-stage costs such as design and add up to “maybe 10%” of the total cost.

- The plan is to recruit a total of about 20 companies as anchor partners and increase the pool of private capital to $3-billion.

- Green hydrogen and sustainable jet fuel are advanced enough that they could “get to a low price” in three to four years.

“I’d be very disappointed if we don’t see a dramatic reduction in the green premium, even in less than five years,” Gates said. “Because that should let us do two rounds of projects, the first projects and then take the learning from those first two-and-a-half years and do a second round that will bring the costs down even further.”

Catalyst is the latest in a series of initiatives that Gates has founded under the Breakthrough Energy banner. A venture capital arm, Breathrough Energy Ventures, raised some of its money from billionaires Jeff Bezos and Michael Bloomberg. Catalyst is run separately and funded independently. — Reported by Erik Schatzker and Akshat Rathi, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP