Microsoft has unveiled software tools designed to make it easier and less expensive for people to access virtual reality and augmented reality content, and for more creators to build these digital and holographic worlds.

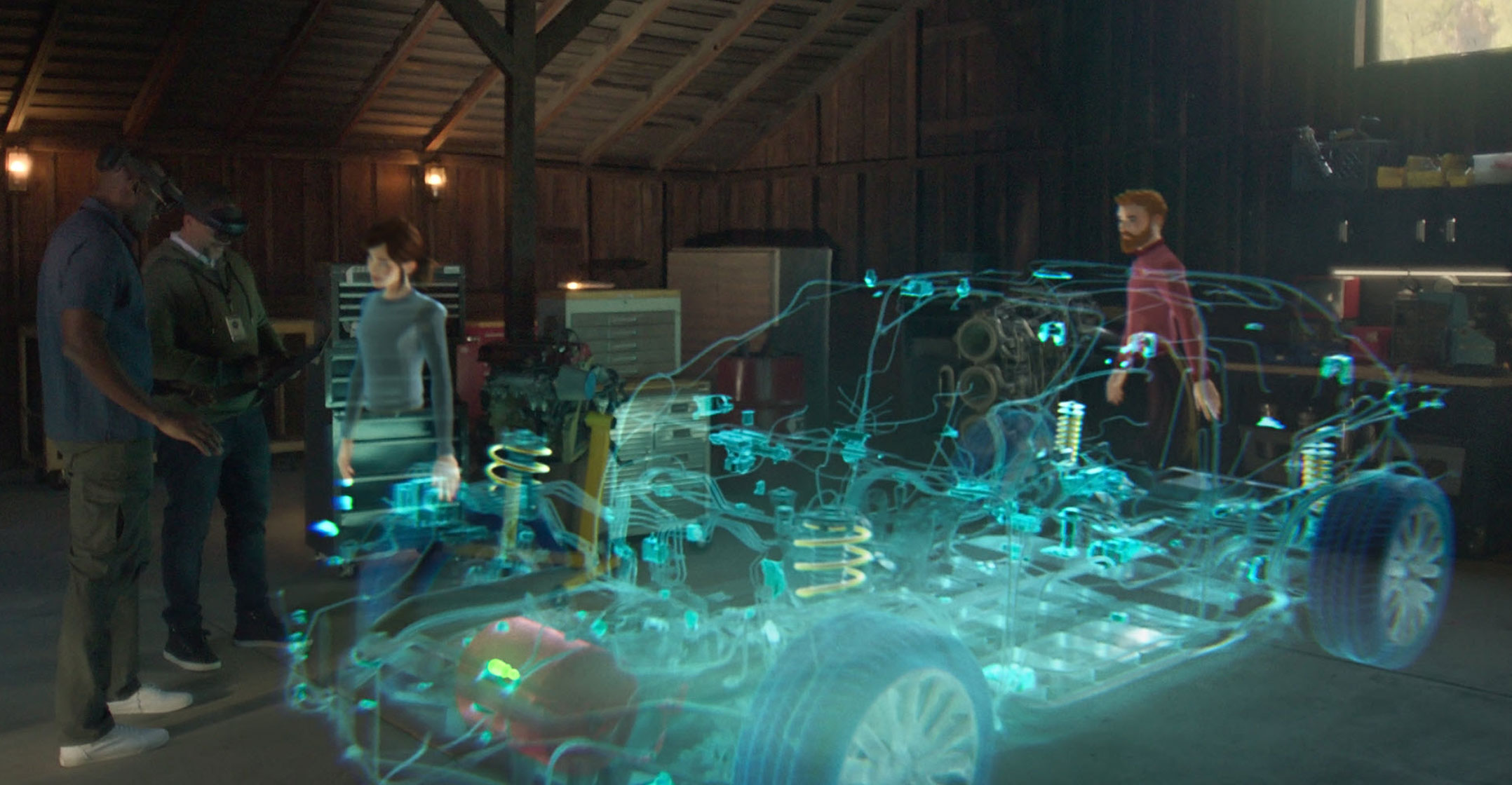

The company’s Mesh software will enable users to work and play together virtually by interacting with the same set of holograms on devices at various price points and from different manufacturers, ranging from Microsoft’s US$3 500 HoloLens augmented reality goggles and Facebook’s Oculus and other specialised VR headsets to cellphones and computers where users can get a 2D view. Mesh also lets multiple people see the same holograms from different locations, allowing for events such as concerts or company meetings where one user attends in person and the other “holoports in” from home.

“You can be anywhere as a hologram or an avatar, and it’s not just you,” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said in an interview. “You now have not just yourself but all of your co-workers or your friends with you and you can do things together, not just with real objects, but with holograms.”

In a demonstration, Microsoft technical fellow Alex Kipman described the product and answered questions through his holographic avatar — a torso, bearded head and pair of disembodied hands — using both a HoloLens and an HP Reverb headset in turn. A school of jellyfish, a shark and two planets floated around the space, all holograms that could be passed back and forth, resized and examined.

The software giant first announced a product in this space in 2015 with HoloLens, a pricey product that has largely focused on corporate uses, like medical imaging and complex equipment repair. Though companies have been touting AR and VR as breakthrough technologies for years, they have yet to gain traction with a wide audience. Facebook, HP and Snap have released various forms of goggles and glasses that use the technology, but augmented and virtual reality still haven’t reached mass appeal save for some lower-end mobile applications, like Niantic’s Pokemon Go AR game. Microsoft is betting that a set of cloud-based tools to make it easier to develop compelling AR and VR applications for almost any type of device will have broader appeal. Nadella said the key is bringing these technologies to the gadgets and platforms that engineers design for and consumers use most, rather than requiring them to jump through additional hoops to access them.

A way in

“There’s always the cost, but there’s also — what’s that ubiquitous device that I have with me always that I can use to interact? It’s not like I have a HoloLens on me — it’s not like I am wearing it right now,” Nadella said. “Whereas, I have a computer right now or I’m using my phone. That’s why Mesh is not just about HoloLens.” Seeing 3D holograms will still require some sort of headgear, Nadella said, but as more AR and VR experiences become available for larger groups, phones and PCs allow a way in without expensive devices.

Based on Microsoft’s Azure cloud, data and artificial intelligence tools, Mesh is available now in preview. Customers can also request access to a Mesh-enabled version of the AltspaceVR meeting app to let companies hold corporate meetings with secure sign-ins and privacy features. Microsoft will roll out additional features in the coming year and is planning to add them to its Teams teleconferencing app.

The Redmond, Washington-based software maker will demonstrate prototypes of how the technology can be used on Tuesday at the company’s Ignite conference in a keynote speech, which Microsoft is also streaming in virtual reality using Mesh.

In one demonstration, Niantic CEO John Hanke will don a HoloLens and hunt for Pokemon near California’s Lake Merritt, joined initially by Kipman’s avatar and later another friend also clad in a HoloLens. Around them, Pokemon frolic in groups, reacting to each other. While the features demonstrated are not yet part of a finished product, Niantic is working on games and services that make use of similar concepts and hopes to use Mesh for things like programming the presence of two or more holograms.

“The thing that’s exciting to me is this notion of mixing the real and the virtual in terms of social interaction,” Hanke said. “In the future you could join from Texas and play with your mom and dad and the kids, or you could join your college roommate in New York City and walk around Central Park playing together virtually, comingled with people in the physical world.”

To Microsoft, the idea of Mesh is similar to that of Xbox Live, the online gaming service the company introduced in 2002 that provided the networking infrastructure so game developers could create online multiplayer games between friends and strangers without having to build that technology themselves, Kipman said.

“Apply that same analogy here with Microsoft Mesh,” he said. “It’s possible today to create experiences with multiple people sharing the same holographic landscape in the room, but it’s significantly hard, and you don’t see a lot of that, because most developers don’t have the time or know-how to be able to do it appropriately.”

Mesh also uses spatial sound to change the audio based on where holograms and people participating are located, giving the user a sense of space in the virtual world. A friend sitting beside another friend’s hologram in a work meeting or at a concert can whisper to their neighbour, for example.

Entertainment events

Hānai World, a new company from Cirque du Soleil co-founder Guy Laliberté, plans to use Mesh to create entertainment events that mix live and virtual aspects. The events will take place in physical venues and through mixed reality headsets, with previews starting at the end of the year. Ray Dalio’s marine science nonprofit OceanX will use the technology to create a holographic table on ships that scientists can gather around, in person or remotely, to view three-dimensional holograms of exploration areas, and Accenture has created a virtual headquarters to bring in new employees and help with connections during the pandemic.

While Mesh makes creating these programs easier, there’s still more work to be done in complex scenarios. For example, to broadcast a DJ set or a concert, developers would have to place sensors around the performers’ space to capture the 3D experience. That’s why sports programming is still a way off, Kipman said — it would require sensor tracking on too many players and too large a space.

Nadella plans to keep investing in VR and AR, likening it to Microsoft’s decision 10 years ago to go “all in” on cloud computing, which took a while to pay off.

“That’s what it takes,” he said. “I don’t think about this as, ‘oh, it’s about HoloLens’, I think of this as Microsoft should — and the industry should — continue to push on how can people communicate, collaborate and build community, whether it’s for work or for play.” — (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP