Netflix has been in the headlines a lot recently, and not in a good way.

There’s news about competitor Amazon launching a monthly video service, subscription fees going up, its library of content shrinking and lower global subscriber gains than the company had anticipated.

But since its launch in 1997, Netflix has always been in the headlines.

Its forays into new territory are often met with suspicion and negative forecasts because of the way it diverges from traditional business models, doing things others have deemed impossible.

As a professor of media studies who researches and writes about TV’s changing business and technological landscape, I’ve been watching Netflix’s growth and evolution with great curiosity. The company, which arguably invented the US subscription streaming business, continues to change how we view television.

Now, as Netflix braces itself to disrupt the model of global television distribution, the company appears poised to remain influential — though, again, in unexpected ways.

It started with a red envelope

For a brief refresher: Netflix began as a video rental by mail service. It then pioneered broadband video distribution, forcing the television and film industries to evolve or be left behind. Next it proved a broadband-distributed service could produce its own films and series.

The latest round of headlines comes as the company pivots toward its next endeavour: becoming a global television and film network.

Like many companies seeking to enter established industries, Netflix built itself on a barely sustainable business model. Companies that require changes in consumer behaviour — like Amazon, with its vast online marketplace — will endure low profit margins for a period of time to encourage people to try their service, whether it’s renting DVDs by mail or buying toothpaste from what you thought was a bookseller.

In Netflix’s case, in order to prove itself as a source of top-rate programming, the company has spent lavishly on licensing content from studios and on developing its own series and movies. All the while, it maintained a low monthly fee of US$8 — about half that of HBO Now.

But now that many millions of US subscribers have come to appreciate the experience of ad-free television and films on demand, long-term sustainability requires increasing profitability.

A 2015 report by industry analyst Matthew Ball noted that Netflix earned only a monthly profit of $0,28 per subscriber (compared with $3,65 for HBO) as a result of its high programming costs, low subscription price and global expansion. Though profitable — which is more than many new media economy businesses can claim — such margins aren’t feasible in the long term.

Now, the company is simply adjusting prices to increase profits.

Notably, even with the planned rate increase, few entertainment sources offer comparable value. A January 2016 analysis by BTIG Research found the average Netflix subscriber streams two hours a day. That average subscriber will pay just $0,17/hour of content after the increase to $10/month.

Going global by cutting out the middleman

For US subscribers, it is important to note the company’s next aspirations are more about the global market and becoming a global television network than growing its US audience. Netflix’s ability to create original programmes and simultaneously self-distribute them internationally marks a new stage of competition in media distribution.

This has enormous implications for the business of television. Admittedly, they’re the parts of the business that most viewers know nothing about, but they’re parts that are nonetheless critical to sustaining media companies.

Netflix’s next strategy bets on vertical integration — that is, on owning its content and using its distribution system to deliver that content to its subscribers. Owning rights and distributing direct to viewers allows Netflix to keep all revenues, rather than sharing with distributors. For example, a distributor such as iTunes keeps roughly 30% of the revenue from the albums, tracks or films it sells.

Reliance on vertical integration is becoming more common throughout television. Ten years ago, AMC contracted with Lionsgate Television to produce Mad Men. As was the norm, Lionsgate later sold the series to various channels around the world to earn back the costs of production and even secured a lucrative licensing deal with Netflix. Now AMC has its own AMC Studios to produce The Walking Dead and has purchased channels around the globe so that it can self-distribute its hits to a wider audience.

While this new stage of Netflix may be best thought of as a global “network”, the fact that it offers a library of content for a fee, rather than a schedule that limits viewers to watching programmes at certain times, makes it part of a wholly new phenomenon.

And new things are often tricky to evaluate.

Music streaming services Pandora and Spotify have tried a similar model, but continue to struggle with converting users from advertiser-supported versions into more lucrative subscription versions. Oddly, the closest precursor for Netflix’s business model may be the circulating libraries of the 1700s.

These libraries existed before public libraries, when books were too expensive for most to afford. Like Netflix, subscribers paid a periodic fee for unlimited access to a library of content. For Netflix, the big difference from these libraries — and from music streaming services — is that they are owning more and more of the content that they’re distributing.

It’s not TV, it’s Netflix

The measures long used to evaluate television — ratings, demographics, time slot — don’t matter to Netflix.

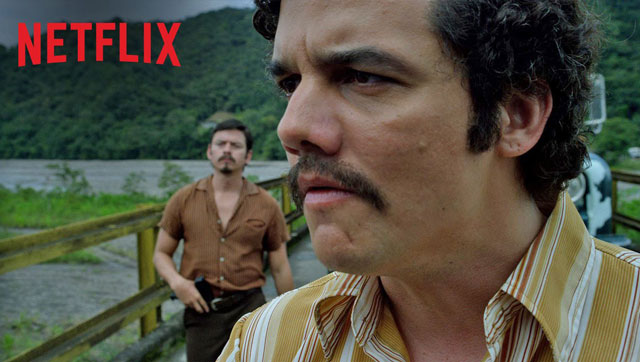

Instead, the value of an original series like Narcos comes when the company owns the series in perpetuity and can distribute it on a global scale. When a distributor owns a show, its value cannot be measured by how many watch it in the first week, month or even year. Netflix is building a library, not a schedule.

Interestingly, HBO is its closest competitor. Like Netflix, HBO produces a portion of its content, has a business model based on subscriber fees and is working toward a global broadband-distributed service.

Both will try to find the right balance of subscriber fees and spending on exclusive, original content to maintain subscribers. As broadband-distributed services, they also are able to gather data about what subscribers watch to learn much more about viewing patterns and the value of each piece of content. And they’ve kept that knowledge to themselves, creating an unprecedented advantage.

In some ways, broadband-distributed portals such as Netflix and HBO Now are merely the next stage of television.

Just as Netflix revolutionised the experience of watching television for US audiences, it’s now on the verge of rewriting the model of global television distribution.![]()

- Amanda Lotz is professor of communication studies and screen arts & cultures, University of Michigan

- This article was originally published on The Conversation