When the competition authorities last year finally approved Vodacom’s acquisition of a 30% stake in Maziv – the parent of Vumatel and Dark Fibre Africa – they quietly reshaped the rules of engagement for South Africa’s digital infrastructure market.

For years, open access has been treated as a policy ideal: shared networks, used on fair and non-discriminatory terms, driving affordability and inclusion. In practice, the market that emerged was fragmented, capital-constrained and uneven. The Maziv decision signalled a pragmatic shift. It recognised that, under the right conditions, scale can enable rather than undermine open access, and that consolidation can serve inclusion rather than simply concentrate power.

“Open Access 2.0” will not be defined by how many networks exist but by how they behave: who can use them, at what price, with which service levels and under what enforcement regime. The question now is whether regulators, investors and operators can turn this model into one that expands coverage, improves quality and sustains competition – or whether consolidation erodes contestability under the banner of openness.

South Africa’s digital policy has long placed open access at its core, from SA Connect’s wholesale vision to the attempted Woan (wireless open-access network). The logic was straightforward: shared infrastructure would reduce duplication, lower costs and extend broadband more widely than parallel buildouts ever could.

In practice, the fixed-line market evolved bottom-up through entrepreneurial fibre network operators such as Vumatel and DFA, which have passed and connected millions of homes and businesses and made fibre broadband a mainstream urban and suburban service. This success came with a structural trade-off. High-income suburbs often host multiple overlapping fibre networks, while many townships, secondary towns and rural areas remain underserved or entirely unserved as capital gravitates towards faster payback.

Concentrated

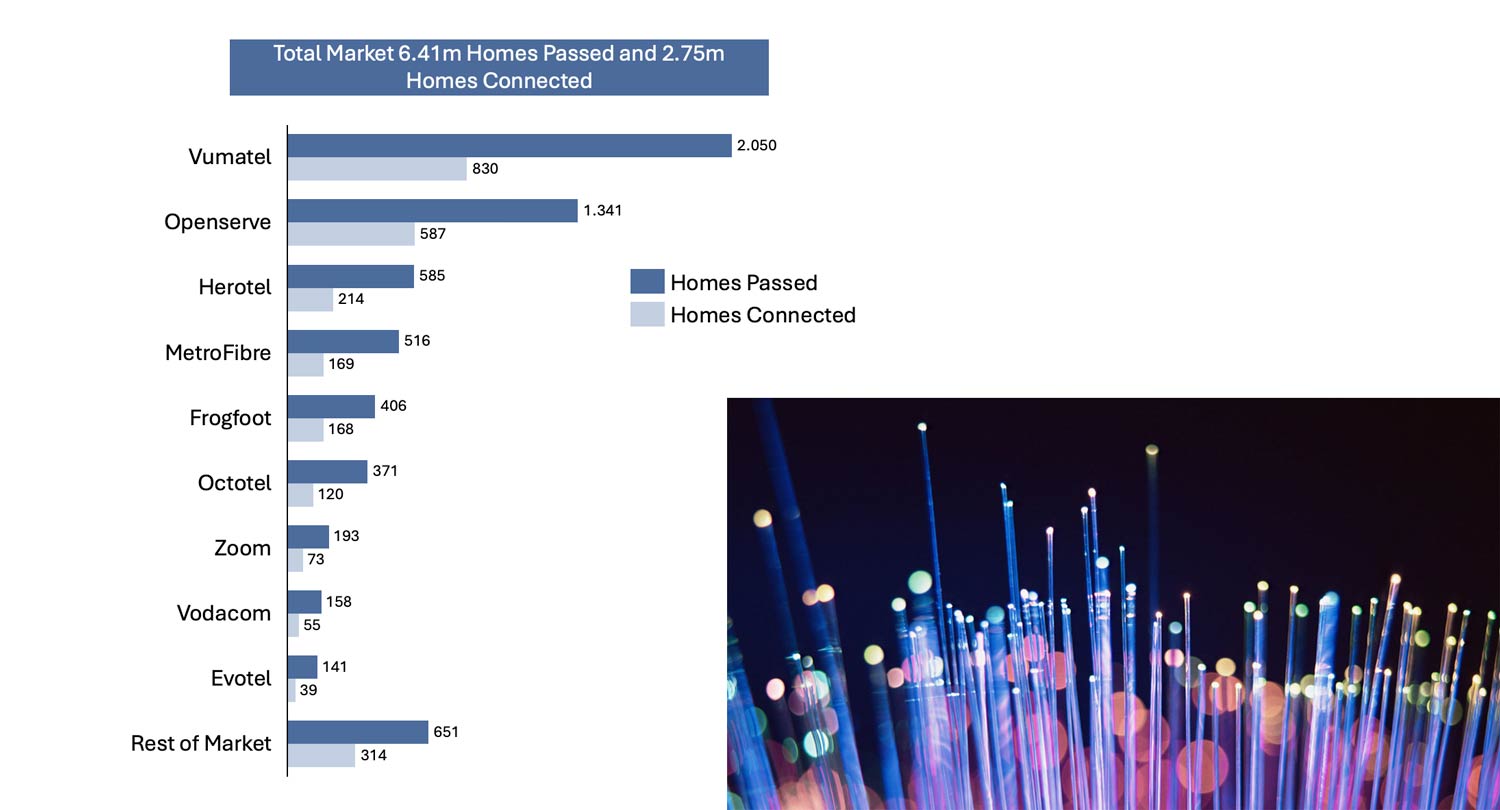

At the wholesale backbone and metro layer, the market is more concentrated. Maziv (via DFA) and Openserve anchor national fibre deployments to mobile towers, enterprises and residential areas, with regional and specialist players filling narrower niches. By late 2024, South Africa had around 6.4 million FTTH homes passed and 2.6 million connected, but only about 5.4 million of those passes were unique, underlining the degree of overbuild in attractive areas and the persistent gaps elsewhere¹.

Globally, this trajectory is not unusual. In the EU39 region, FTTH/B coverage reached close to 70% of households by 2023², while penetration remained nearer 35%, illustrating that once supply exists, adoption and affordability become the binding constraints. South Africa faces a similar dual challenge: driving higher take-up in fibre-ready suburbs while finding viable models for low-income and low-density areas where the economics are far more fragile.

TCS | Maziv CEO Dietlof Mare on Vumatel’s big roll-out plans

Against this backdrop, the approval of Vodacom’s co-controlling stake in Maziv is more than a single transaction. It is a structural signal that scale is no longer viewed as inherently incompatible with competition. Regulators have accepted that large, well-regulated platforms may be better placed to sustain investment, extend coverage and support fibre-hungry use cases such as 5G backhaul and edge data centres.

Crucially, the conditions attached to the deal go to the heart of open access. Non-discriminatory wholesale access, pricing oversight and mandated coverage in lower-income communities turn consolidation into a conditional privilege. Fewer, stronger networks are acceptable only if they remain genuinely open and use their balance sheets to push deeper into underserved areas. This reframes competition away from the number of networks towards enforceable wholesale behaviour.

The deal also accelerates convergence. Vodacom now sits across national backhaul, metro rings, last-mile fibre and mobile access, creating opportunities for integrated fibre-wireless planning. At the same time, it raises the stakes for regulatory oversight as 5G and future technologies depend ever more heavily on robust, multi-tenant fibre infrastructure. The combined platform will set the benchmark against which future infrastructure deals – including any potential MTN/Telkom transaction – are judged.

Future consolidation

The Maziv transaction opens the door to a broader consolidation wave. Mid-tier fibre players may reassess their options in a market where scale has been legitimised, provided openness is preserved. National backbone operators are likely to play an anchoring role, while regional networks may seek mergers or partnerships simply to remain relevant.

On the mobile side, consolidation has long been framed as strategically necessary. A future in which Vodacom/Maziv forms one axis and an MTN/Telkom combination emerges on the other is no longer unthinkable, with wholesale fibre platforms acting as critical swing players in how contestable the market remains.

For policymakers and regulators, the debate shifts from whether consolidation should occur to how it is shaped. Mergers can reduce duplication, unlock synergies and enable more coherent national planning of fibre and 5G, but only if approvals are tied to time-bound obligations on coverage, wholesale pricing trajectories and service quality. Done well, inorganic growth becomes a tool to close investment gaps; done poorly, it entrenches market power and weakens open access in practice.

The emerging model reframes open access as a behavioural and contractual regime rather than a simple structural shorthand. True openness depends less on the number of networks and more on the consistency and enforceability of wholesale terms as capital intensity rises and only a few platforms can sustain national-scale investment.

Regulators are increasingly favouring fewer, stronger networks operating under clear wholesale obligations over many small networks offering inconsistent or opaque access. Transparent reference offers, cost-based pricing tests and rigorous SLA monitoring are the mechanisms that prevent scale from turning into exclusion. In this context, large platforms can, in practice, deliver more meaningful openness than a fragmented field of localised monopolies.

Coherent playbook

A coherent playbook is required. Merger approvals, spectrum assignments and major infrastructure projects should be linked to measurable outcomes: additional homes passed in underserved municipalities, connected schools and clinics, and wholesale price ceilings for entry-level products. At the same time, policy must support mid-tier and regional operators through predictable access to national backbones, streamlined wayleaves and encouragement of wholesale-only models that can interoperate with larger platforms.

The model carries real risks. Weakly designed or poorly enforced conditions could allow consolidation to harden into harmful concentration, with open-access commitments eroded through opaque pricing, unmonitored SLAs or subtle discrimination that smaller ISPs struggle to challenge.

Read: Four years later, Vodacom and Maziv have sealed their deal

Scale also has limits. Even efficient national fibre operators face difficulty justifying standalone investment in deep rural and sparsely populated areas. Without complementary instruments such as targeted subsidies, demand aggregation for public services and stronger incentives for infrastructure sharing, the rural economics problem will persist.

Finally, convergence brings execution risk. Integrating networks, systems and operating models can absorb management attention that should instead focus on improving wholesale offers and service quality. If openness becomes a compliance afterthought, the promise of Open Access 2.0 will remain unrealised.

The Maziv/Vodacom transaction marks a strategic inflection point for South Africa’s digital infrastructure. Open access is evolving from a fragmented, policy-driven aspiration into a scaled, market-enabled framework in which consolidation and competition can reinforce each other – but only if scale is carefully earned and tightly governed.

Whether this becomes South Africa’s true Open Access 2.0 moment will depend on three factors: disciplined enforcement of wholesale obligations, alignment of investment incentives with universal service goals and the willingness to deploy additional instruments where commercial logic falls short. Handled well, scale, openness and innovation can become mutually reinforcing. Handled poorly, consolidation risks entrenching a more concentrated market that falls short of the country’s ambitions for universal, affordable connectivity.

- The authors are Björn Menden, a partner at Altman Solon, based in Dubai, with a focus on telecoms and digital infrastructure across Africa and the Middle East, and Thomas Switala, managing partner at Switala Ventures, a boutique advisory focused on digital infrastructure and TMT M&A

¹ Remgro Capital Market Day, CIVH-Maziv, April 2025

² Omdia Fibre Index

Get breaking news from TechCentral on WhatsApp. Sign up here.