A nuclear programme cannot be implemented in a fiscally responsible way in the current economic growth environment, an analyst warns.

“Any single way you look at it, nuclear does not work in the current growth environment. It blows our metrics out further away from the emerging market investment grade average of a 50% [debt-to-GDP ratio],” Nishan Maharaj, head of fixed interest at Coronation, says.

If the nuclear programme is implemented, fiscal consolidation will not become a reality, he adds.

“In the current environment of 1%-1,5% growth, this is not going to materialise. If you are going to implement it [nuclear], or lean towards implementing it, it is going to result in us moving further and further away from investment-grade status.”

This is one of the key reasons why rating agencies reacted as aggressively as they did after the cabinet reshuffle, he says.

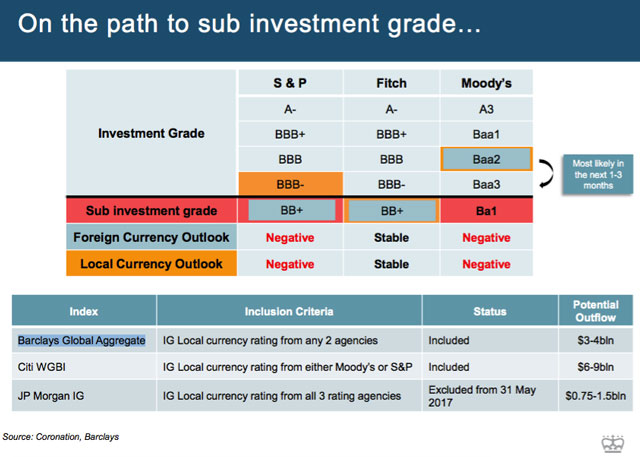

S&P Global Ratings lowered South Africa’s sovereign credit rating to junk in April, but kept the local currency rating one notch above sub-investment grade. Fitch downgraded the country’s local and foreign currency rating to sub-investment grade (see table below).

This came after President Jacob Zuma removed respected finance minister Pravin Gordhan in a midnight cabinet reshuffle. The decision raised fears that South Africa would digress from its path of fiscal consolidation and forge ahead with an expensive nuclear build programme, decisions that could see the country plunge into a downgrade spiral.

On 26 April, the high court ruled that government’s nuclear plans were invalid.

Maharaj says although the economy seems to be in a sweet spot with inflation moderating and growth accelerating, the deterioration of South Africa’s debt and fiscal metrics still posed considerable risk in the long term.

Although expectations are that GDP growth will accelerate to around 0,9% this year from 0,3% in 2016, the low-growth scenario and the fact that many state-owned enterprises — notably Eskom and South African Airways — still require additional support, will result in a further deterioration of the country’s debt-to-GDP numbers, he says.

The table below sets out the rating agencies’ views on South Africa’s investment grade rating, the criteria for inclusion in various global bond indices and the current status.

Maharaj says a number of bond indices in which South Africa is included require an investment grade rating on the local currency rating. Following Fitch’s decision to downgrade South Africa’s local currency rating to sub-investment grade, the country will be excluded from the JP Morgan Investment Grade Index, triggering around US$1bn of outflows.

If either S&P or Moody’s moves South Africa’s local currency rating to sub-investment grade, it will trigger an exit from the Barclays Global Aggregate Index and outflows of around $3-4bn.

Although this will be harder to digest, it will not be the end of the world, he says.

However, if both S&P and Moody’s adjust the local currency rating to sub-investment grade it will trigger an exclusion from the Citi World Government Bond Index and outflows of between $6bn and $9bn.

A “worst-case scenario” will result in outflows of between $10bn and $13bn from the local bond market.

Although such a scenario would have serious implications for the economy, their base case is not that both S&P and Moody’s would downgrade the local currency rating in the near future. However, the expectation is that S&P would downgrade the local currency rating over the next 12 months, Maharaj says.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission