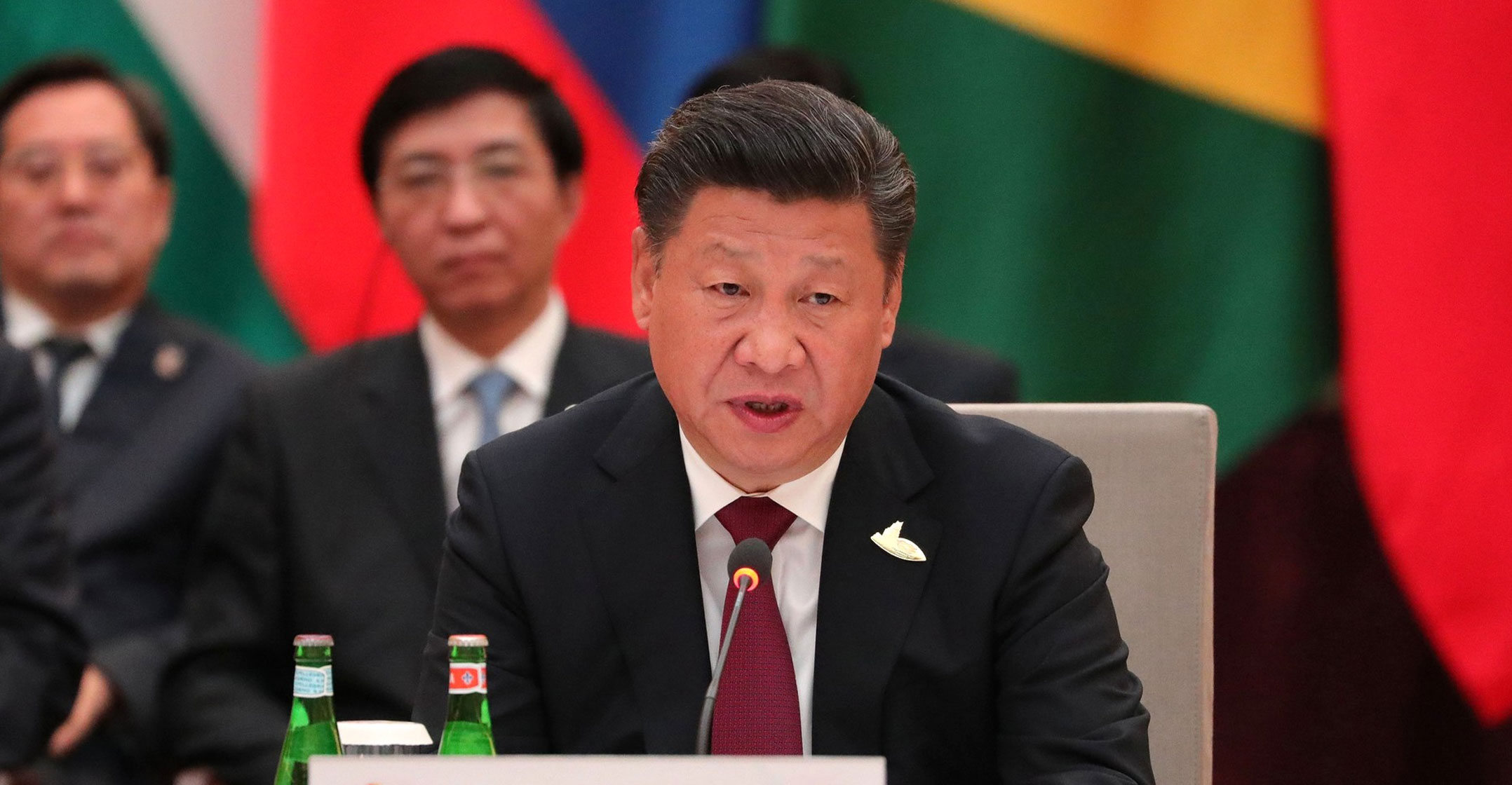

For US politicians, China’s potential to dominate sensitive, cutting-edge technologies poses one of the biggest geopolitical threats of the next few decades. President Xi Jinping is similarly worried the US will block China’s rise, and this week will unveil plans for greater self-sufficiency.

At an annual session of China’s legislature, top Communist Party leaders will approve a five-year policy blueprint to cut dependence on the West for crucial components like computer chips while also making big bets on emerging technologies from hydrogen vehicles to biotech. The push to mobilise trillions of dollars could help China surpass the US as the world’s biggest economy this decade and cement Xi’s goal of turning the nation into a superpower.

“The most important thing is the magnitude of the ambition — this is bigger than anything Japan, South Korea or the US ever did,” said Barry Naughton, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, and one of the world’s top researchers on China’s economy. “The ambition is to push the economy through the gateway of a technological revolution.”

The race to develop the most advanced technology is stoking US-China tensions following decades of integration that raised living standards around the globe. Now both countries are aiming for self-sufficiency in strategic areas, each fuelled by fear the other wants to upend their political system: One that sees free speech and democracy as essential to prosperity, and another that puts one-party rule above individual liberty to deliver economic growth.

At stake for Xi is more than just improving the lives of China’s 1.4 billion people, which is key to the Communist Party’s justification for effectively banning political opposition. He also wants to show the party can play a successful role in guiding the economy, particularly after US President Donald Trump’s administration sought to undermine its legitimacy to rule and destroy national champions such as Huawei Technologies and Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp, China’s largest microchip manufacturer.

Confidence

Beijing’s confidence in its political system has grown after it quickly contained Covid-19 following delays by local officials in sharing information that allowed it to spread around the globe. Economists predict China’s economy will expand 8.3% this year, compared to 4.1% in the US. “The pandemic once again proves the superiority of the socialist system with Chinese characteristics,” Xi said last year.

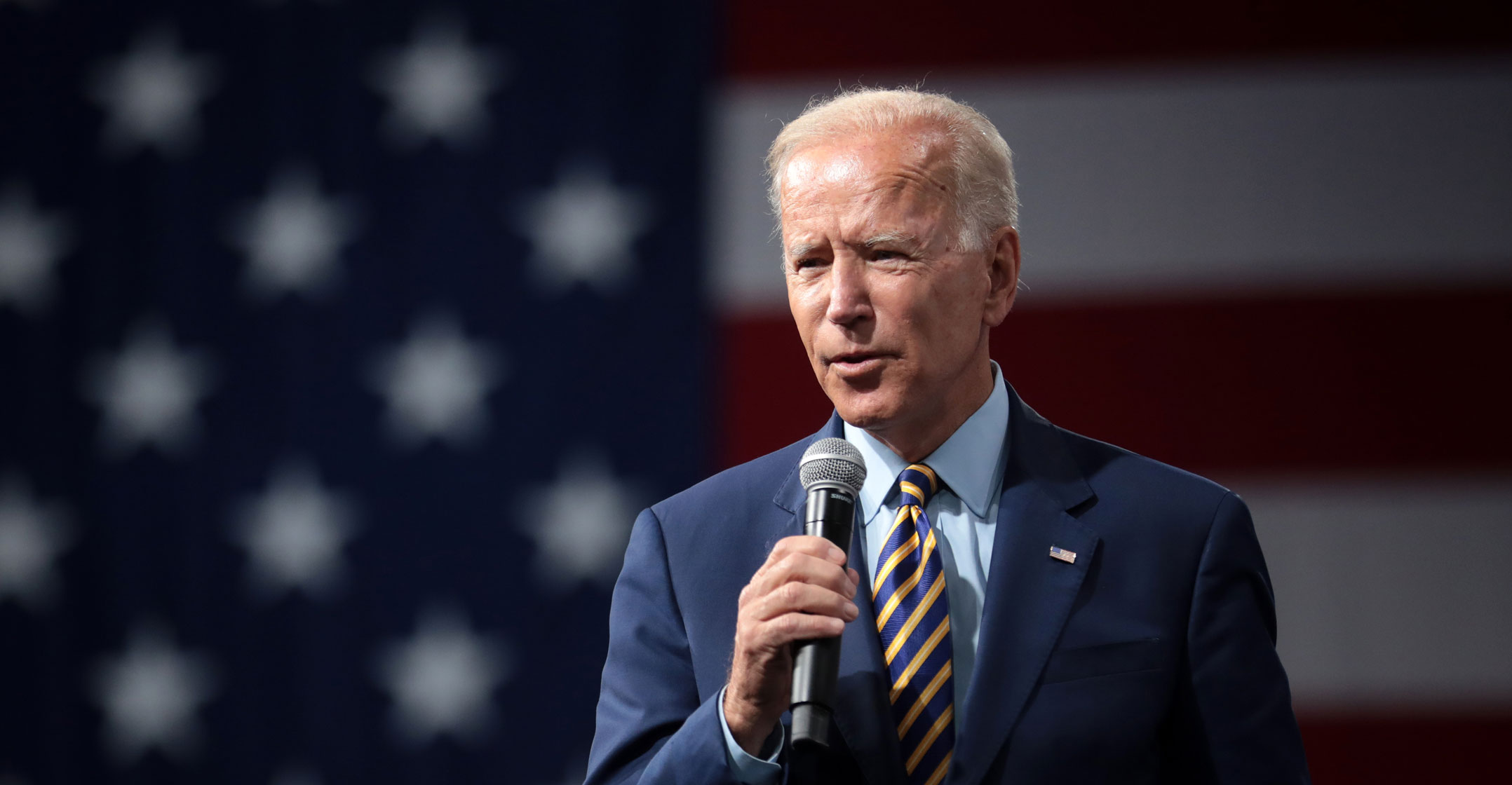

But the US is now looking for allies to help thwart Xi’s aspirations, both through denying Beijing access to key technology and shoring up its own supplies of strategic goods. Last week, US President Joe Biden announced a wide-ranging supply-chain review of semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, rare-earth metals and high-capacity batteries, part of a broader plan to out-compete China that includes US$2-trillion in infrastructure spending.

“If we don’t get moving, they’re going to eat our lunch,” Biden told reporters in February after holding his first call with Xi. EU trade commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis separately highlighted concerns that Beijing was giving unfair advantages to Chinese companies, telling Bloomberg Television last month that the bloc would cooperate with the US on challenges stemming “from the socioeconomic model of China”.

Global investors are closely watching the National People’s Congress session, which starts on Friday and runs for about a week. While the Communist Party has shown it can quickly channel billions of dollars to control the supply chains of emerging sectors like solar power and electric vehicles, it has also swiftly reined in the private sector if risks escalate — seen most recently by the 11th-hour halt of an initial public offering by billionaire Jack Ma’s Ant Group.

Premier Li Keqiang will outline plans on Friday to keep the economy humming over the next 12 months, which may include fresh measures to boost consumption even as he stops short of giving an official growth target for a second straight year. Perhaps more importantly, the legislative session will also reveal details of longer-term plans to develop more than 30 “choke-hold” technologies China currently can’t produce, from chip-making equipment to mobile phone operating systems to aircraft design software.

The focus on technology is more urgent due to the waning efficiency of China’s economic model, which has relied on channelling credit into property investment and infrastructure to shore up growth. Yet with housing sales peaking as urbanisation slows and local governments struggling to find viable infrastructure projects, Beijing must leverage technology to boost productivity in order to meet a 2035 target of doubling the size of its economy from 2020 levels.

One key number to watch is spending on research and development: Authorities are expected to reveal a target that will match or exceed US annual spending of around 3% of GDP. More will be allocated to state-funded research, with China’s science & technology ministry announcing priority areas such as hydrogen energy, electric vehicles and supercomputing.

From 2014 to 2019, China’s government raised at least 6.7-trillion yuan ($1-trillion) in a series of venture-capital funds to take stakes in hi-tech companies, according to estimates from Naughton at the University of California, San Diego. China has already announced plans to invest $1.4-trillion from 2020 to 2025 in hi-tech infrastructure, from artificial intelligence to 5G base stations to high-speed rail.

Mixed record

“If that does end up paying off and Xi Jinping is able to engineer a more centrally steered growth model, then China will overcome the long list of challenges that it’s facing domestically,” said Jude Blanchette, a researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “If the state-led model is as unproductive as many think it is, then China will have wasted a generation’s capital pursuing a dream of centrally planned technological innovation.”

China’s record of success is mixed. An example of what Beijing has in mind is biotech, which barely existed in China a decade ago and was earmarked as a “strategic industry” in the most recent five-year plan. From 2016 to 2020, the market capitalisation of publicly listed Chinese companies developing innovative drugs rose from $1-billion to $217-billion, according to McKinsey. In 2019, the first China-developed cancer treatment was approved in the US.

The main area in which China has struggled is chip making, with its top companies still at least five years behind global rivals. China’s five-year plan will include measures to boost financing for semiconductors, treating the sector with the same kind of priority it once accorded to building its atomic capability.

But there’s no guarantee it will work — and the avalanche of state-directed investment risks spawning bad debt that destabilises China’s economy. A taste of such a possibility came last year, when state-owned Tsinghua Unigroup, whose investments in chip production failed to pay off, roiled financial markets by defaulting on $2.5-billion of debt.

To reduce waste, Beijing has signalled that it would continue to rely predominately on private companies to meet its technology goals through tax breaks, direct investment in start-ups and minority stakes in promising but financially troubled companies. Beijing also wants more investment from foreign companies such as Tesla, as long as they help meet the goal of upgrading China’s technology.

While the West sees Xi’s ambitions as a threat, Beijing’s push to achieve self-sufficiency is mainly a defensive move by the Chinese Communist Party, according to Meg Rithmire, an associate professor at Harvard Business School.

“If the CCP thought there were no dark storm clouds on the horizon,” she said, “I don’t think they would be taking such a heavy hand. It’s a risk-management mindset.” — (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP