The much anticipated return of Top Gear to the BBC raises a big broadcasting question: is the post-Jeremy Clarkson version doomed to fail or will it help sustain the brand’s success?

The stakes are high for the corporation. Top Gear is widely acknowledged as one of the world’s most successful TV shows, with a weekly audience of 350m viewers across 212 territories. The brand expands well beyond TV screens and is a multi-platform entertainment franchise valued at US$1,5bn .

Brand expansions include a magazine, website, road trip DVDs, mobile games (7.9m downloads), Top Gear Track Experience and Top Gear Live. All that seems to be missing is a Top Gear cruise. Its social media has gathered 21m Facebook fans, 1,9m Twitter followers and 4,8m YouTube subscribers. The show is also a popular TV format that has been adapted in seven countries so far, including Australia, China, France, Italy and the US.

But a change of team does not need to be traumatic as the key to intellectual property is who owns it, not who creates it. The world is full of entertainment franchises that have thrived long after their founder departed. The latest example is Star Wars, with new owner Disney not bothering to consult George Lucas for the franchise’s latest instalment. Many have speculated on the key ingredients behind Top Gear’s popularity, but much of its success resides simply within the mechanisms of factual entertainment.

The genre was invented by British TV producers in the 1990s who transformed dull lifestyle shows on cooking or gardening by carrying over rules and format ideas from light entertainment programmes in order to engineer drama, excitement and comedy. The two prime examples are MasterChef and Top Gear. Similar to MasterChef — once a pedestrian Sunday afternoon cookery show — Top Gear started life as a mundane automotive programme in 1977 and was given a makeover in 2002.

As with any good TV format, Top Gear has rules and segments designed to deliver gripping stories. These include a news section, an interview with celebrities that concludes with a lap in an “affordable” car, a power lap that times some of the world’s fastest cars around a track, the Stig, the nameless racing driver, and a few catchphrases. All these elements are part of the fabric of the show can and be used and adapted by the incoming team. Equally importantly, some of them are proprietary and non-transferable when presenters who deliver them then leave.

The new presenting team is certainly more inclusive than three white British males, but above all the choice of presenters is commercially shrewd. From German racing driver Sabine Schmitz, to Friends star Matt LeBlanc, the selection ensures renewed interest for the series from two of the world’s wealthiest media markets.

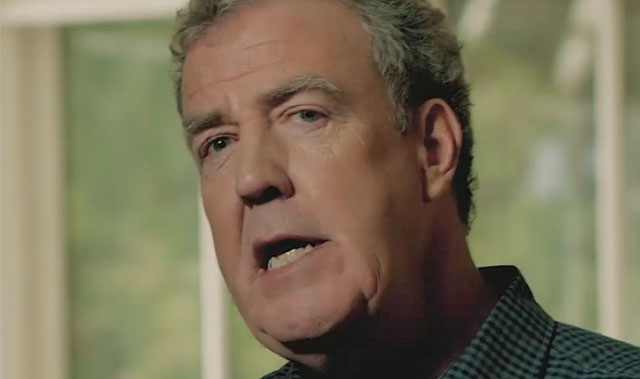

However, the departure of Clarkson, Richard Hammond, James May — and executive producer Andy Wilman — means the BBC has lost something precious. Gone is the extraordinary chemistry between three friends “who genuinely loathe each other” which gave the show an all-important feeling of authenticity, intimacy and freshness. Scripted jokes sound much better when delivered among mates than facing a camera. And despite the despondency of social critics, an all-male cast gave the show an entertaining twist and a perspective which resonated with fans. As Wilman explained: “It is a journey into the male mind, which I believe is potentially a very funny place, because let’s face it, nothing happens there.”

Left in the dust

Without Clarkson, BBC executives will face fewer sleepless nights and save tons of cash on lawyers’ fees, but they are also losing a gifted journalist with a good eye for a story.

And without the departed team, the BBC may have lost the taste and hunger for stunts that may have been controversial (such as driving around Argentina with a number plate which appeared to make reference to the 1982 Falklands conflict) but were spectacular and added an element of unpredictability to the show. The BBC also faces hostility from large sections of the British tabloid press, notably the Daily Mail and The Sun, both of which rarely miss an opportunity to malign the revamped Top Gear and its new host, DJ Chris Evans.

But the real secret to Top Gear’s success probably lies in its unique combination of elements and its ability to combine intimacy and familiarity — viewers tuning it to see household names and friendly faces — with unpredictable elements that keep viewers returning to be kept on the edge of their seats.

The new Top Gear will just need a bit of both in order to retain its allure.![]()

The first episode in the new season will be broadcast this Sunday, 29 May.

- Jean Chalaby is professor of sociology, City University London

- This article was originally published on The Conversation