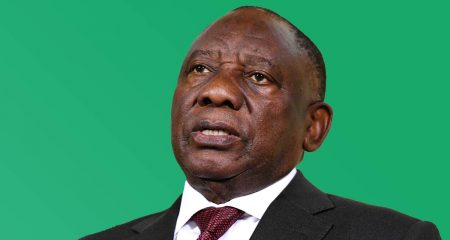

South Africa’s deputy president, Cyril Ramaphosa, has confirmed his availability to contest the presidency of the ANC at its 54th national conference later this year. He has already secured the endorsement of trade union federation Cosatu.

He failed in his bid to lead the party once before. Twenty years ago, his comrades Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma were chosen ahead of him for the top two jobs at the party’s 1997 Mafikeng Conference. If his dream is going to be realised this time he is going to have to take on a major task of convincing ANC branches of his suitability.

Ramaphosa will need a restoration and renewal narrative to convince them. He’ll need to show he has a plan to rebuild the party, and inspire its cadres sitting on the side-lines to join in his renewal efforts.

If successful, he will need to switch immediately to election campaigning mode. The country goes to the polls in 2019 and he will have to do everything in his powers to salvage the former liberation movement’s declining electoral support.

For South Africans at large, he will need to show how the ANC as a brand can reclaim its sentimental and inspirational traits to warrant their trust.

These tasks seem insurmountable when one considers the extent of damage done to the party since Zuma’s rise to power was solidified at the ANC’s bitterly divisive Polokwane conference in 2007. But Ramaphosa has faced seemingly insurmountable tasks of building organisations in challenging times before. He has also served in various international organisations and has been a member of teams appointed to help countries in transition.

He will need to draw on all this experience to succeed.

Born on 17 November 1952, Ramaphosa is from a generation I regard as the agitators in the struggle for South Africa’s liberation. Inspired by Steve Biko, among others, this generation — born in the early 1940s to late 1960s — injected greater momentum to the fight against apartheid in the 1970s and 1980s.

As a young person, Ramaphosa was an active member of the erstwhile Student Christian Movement (SCM) at Sekano-Ntoane High School in Soweto. His evangelical experience cannot be understated in the task that confronts him now. Much like the biblical character Nehemiah, his task is to inspire a dejected and hopeless people with a new vision.

That will not be a new experience for Ramaphosa. While pursuing standard 9 and 10 at Mphaphuli High School in his parents’ village of Sibasa in Venda, he built a stronger SCM within a short time. This was after he was elected to its leadership in the first year of his arrival.

The same happened when he went to study at the then University of the North (now University of Limpopo). The SCM was weak and seen by some as a tool of domination. Ramaphosa worked tirelessly with Frank Chikane and others to turn it into a vibrant organisation. It became a vehicle of struggle when the Black Consciousness student movements were banned.

Ramaphosa’s claim to fame, however, is the work he did in founding the National Mineworkers Union (NUM) in the early 1980s. The NUM operated under the auspices of the Council of Unions of South Africa. Until then, attempts to unite mineworkers and fight for their representation in the mines had failed.

The fact that Ramaphosa was able to build a union in a mining industry fraught with ethnic politics, worker fragmentation and a history of state-sanctioned exploitation attests to his organisation building capabilities. This is especially so considering that he had never worked on the mines himself.

Ramaphosa’s colourful leadership continued over the next three decades across various settings. He became the ANC’s chief negotiator during the country’s transition from apartheid to democracy, beating ANC president Oliver Tambo’s protégé, Thabo Mbeki, to the position.

Ramaphosa became the secretary general of the ANC at its 1991 national conference in Durban after out-campaigning Zuma. He was succeeded in the position in 1997 by Kgalema Motlanthe, with whom he had worked at the NUM.

As the chief negotiator of the ANC, he managed the negotiating committee. He showed great leadership, alongside the National Party’s counterpart Roelf Meyer when the talks broke down.

Ramaphosa became a member of parliament in 1994 and headed the constitutional assembly which drew up the final constitution of the republic. This was finally approved — to international acclaim — in 1996.

But after his crushing defeat by Mbeki to the post of deputy president in 1997, Ramaphosa went into business but maintained some involvement in politics. He was to make a sterling return 15 years later when he was elected ANC deputy president in 2012 at the 53rd national conference in Mangaung (Bloemfontein).

Ramaphosa the businessman

Ramaphosa was among the first beneficiaries of the first wave of equity-based black economic empowerment deals in 1997. In partnership with medical doctor and anti-apartheid activist Nthato Motlala, he joined New African Investment Limited. From those early beginnings, he was to form Shanduka Group, an unlisted entity with interests in resources, energy, real estate, banking, insurance and telecommunications.

He also chaired a number of South Africa’s largest companies, such as Bidvest Group and MTN, and held nonexecutive board positions of others such as Standard Bank and SABMiller.

His most controversial role was as a nonexecutive member of the mining group Lonmin’s board. Shanduka was a minority shareholder in Lonmin, which owned the mine in Marikana where 34 miners were shot by police in 2012.

Leadership qualities

Ramaphosa has the leadership experience to salvage the ANC and become a great president with a wide range of skills. He has the potential to restore hope at the top of the ANC following a period of mediocrity and scandal.

However, while he has a chance in convincing ANC members of his potential, the broader South African public will be even harder to convince. Firstly, as a key player at Lonmin, Ramaphosa is seen as having failed to improve the working conditions of the mineworkers he fought for in the 1980s.

Secondly, his relationship with Zuma, whom he has served as deputy president, has led to some awkward questions. Until last year he appeared to be complacent — or actively defended — Zuma even as the president became more deeply embroiled in alleged corruption scandals. This silence was evident even when Zuma was accused of violating the constitution Ramaphosa was party to creating.

It may be that Ramaphosa has the restoration and renewal narrative — as well as the organisational building skills and tenacity — to turn his own fate and that of the ANC around, but it’s going to be a “long walk” as he put it. Time will tell.![]()

- Ongama Mtimka is lecturer and PhD candidate, department of political & conflict studies, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation