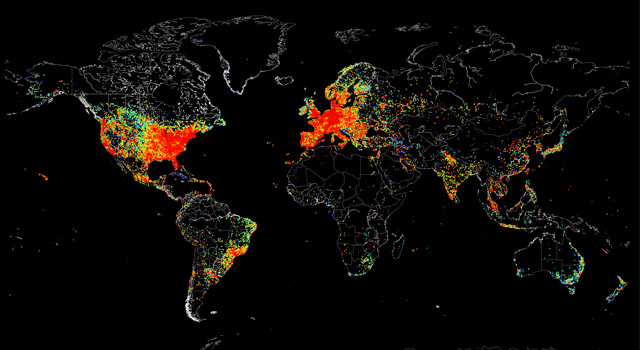

The Internet today is far bigger and more inextricably linked to our daily lives than its creators in the 1970s and 1980s could have imagined. So perhaps it is not surprising that some of the structures put in place decades ago may have failed to keep pace with its rapid evolution.

Chief of these is perhaps the nonprofit organisation Icann, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. Icann is responsible for the key roles of assigning the unique Internet protocol (IP) addresses that locate individual websites on the Net, and managing the domain name system (DNS), which translates the human-readable Web addresses we type into IP addresses (such as 192.68.0.1). Its policy decisions have an important impact on the Internet’s evolution, for example the recent expansion of top-level domain names.

However, since Icann was established in 1998, its contractual links with the US department of commerce have led to criticism of a perceived US and Anglo-centric bias. Controversies such as the original rejection of the .xxx domain name for pornography led to criticism that the US had too much sway over Icann’s decisions, and calls for Icann to disassociate itself from the US, or be replaced with a truly independent, global agency, increased.

Icann’t remain so US centric

The Icann-US government relationship has been steadily renegotiated, first in a 2009 Affirmation of Commitments that released Icann from direct government control but allowed continued influence over certain activities such as the key function of issuing IP addresses.

This accelerated after Edward Snowden revealed the extent of global US surveillance, which led to a group of core Internet organisations releasing the Montevideo Statement on the Future of Internet Cooperation in 2013, calling for the speedy de-Americanisation of Icann’s functions and the creation of a more global, equitable basis for Internet governance. That Icann’s own president and CEO Fadi Chehadé was among the signatories is thought to have spurred the US government on to pass the bipartisan Domain Openness Through Continued Oversight Matters (Dotcom) Act in June 2015.

Congress now has a short window in which to approve the transition plans and temporarily extend the current agreement, if needed, past the expiry date of 30 September.

Breaking up is hard to do

What next? Icann is to transfer its functions to a multistakeholder organisation — a power-sharing agreement between governments, civil society, the private sector and other interested parties. This is a worthy approach but a firm guiding hand is needed to ensure the whole enterprise does not become a talking shop unable to make any decisions.

An Icann Transition Coordination Group has been set up to manage the transition, and a 199-page final transition proposal is open for public comment until 8 September.

However, the true complexity of this process has become apparent. Due to the overwhelming number of interested parties wanting a role in proceedings, it is unlikely any agreement will be reached by the deadline.

Uncharted waters

Under the proposals, Icann’s IP address-assigning functions would be contracted out to a separate entity, overseen by staff drawn from domain name registries, with powers to make changes. There will also be an Iana review process that, as a last resort, could recommend that the contract be terminated. Anyone with a reasonable claim to be involved can be, and this way oversight is shared by a range of groups in a process that should provide balance.

Crucially, there is no direct role for any government or intergovernmental body, with the only route of influence through the Governmental Advisory Committee, which has around 140 governments as members and 30 intergovernmental organisations as observers and advises the Icann board on wider policy issues. Like Icann, this committee has also drawn criticism for being a mouthpiece of western governments. However, any pressure applied by governments will come up against the slow-moving behemoth that is Icann’s internal procedures, which require consensus from many advisory and technical committees.

Another body expected to assert its influence is the International Telecommunication Union, the UN’s IT and telecoms agency. While it is a specialist organisation composed of many commercial and nongovernmental expert groups, like the UN it is a member-state organisation. In the past, the union has been put forward as a body that could fulfil Icann’s governance functions, moving away from perceived western-centrism. But as a body comprised of national government members, greater involvement could lead to a more “top-down” form of Internet control subject to the whims of international relations between members and their national and commercial interests.

Icann has many flaws, but its lengthy, measured deliberations have guided the Internet in its evolution to its current state as an open, interoperable, worldwide network. The alternatives could be so much more damaging to the essential need for the Internet to remain open and transparently governed. The proposals put forward would maintain elements of this; whether Icann’s restructure will be resistant to political pressure remains to be seen.![]()

- Catherine Easton is lecturer at the Law School at Lancaster University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation