Academic plagiarism is no longer just sloppy “cut and paste” jobs or students cribbing large chunks of an assignment from a friend’s earlier essay on the same topic. These days, students can simply visit any of a number of paper or essay mills that litter the Internet and buy a completed assignment to present as their own.

These shadowy businesses are not going away anytime soon. Paper mills can’t be easily policed or shut down by legislation. And there’s a trickier issue at play here: they provide a service which an alarming number of students will happily use.

Managing this newest form of academic deceit will require hard work from established academia and a renewed commitment to integrity from university communities.

In November 2010, the Chronicle of Higher Education published an article that rocked the academic world. Its anonymous author confessed to having written more than 5 000 pages of scholarly work per year on behalf of university students. Ethics was among the many issues this author had tackled for clients.

The practice continues five years on. At a conference about plagiarism held in the Czech Republic in June 2015, one speaker revealed that up to 22% of students in some Australian undergraduate programmes had admitted to buying or intending to buy assignments on the Internet.

It also emerged that the paper mill business was booming. One site claims to receive 2m hits each month for its 5 000 free downloadable papers. Another allows cheats to electronically interview the people who will write their papers. Some even claim to employ university professors to guarantee the quality of work.

Policing and legislation becomes difficult because the company selling assignments may be domiciled in the US while its “suppliers”, the ghost writers, are based elsewhere in the world. The client, a university student, could be anywhere in the world — New York City, Lagos, London, Nairobi or Johannesburg.

If the companies and writers are all shadows, how can paper mills be stopped? The answers most likely lie with university students — and with the academics who teach them.

The anonymous writer whose paper mill tales shocked academia explained in the piece which kinds of students were using these services and just how much they were willing to pay. At the time of writing, he was making about US$66 000 annually. His three main client groups were students for whom English is a second language; students who are struggling academically and those who are lazy and rich.

His criticism is stinging:

I live well on the desperation, misery and incompetence that your educational system has created.

Ideally, lecturers in the system of which he’s so dismissive should know their students and therefore be able to detect abnormal patterns of work. But with large undergraduate classes of 500 students or more, this level of engagement is impossible. The opportunity for greater direct engagement with students rises at postgraduate levels as class sizes drop.

Academics should also carefully design their methods of assessment because these could serve to deter students from buying assignments and dissertations. Again, this option is more feasible with smaller numbers of postgraduate students and live dissertation defences.

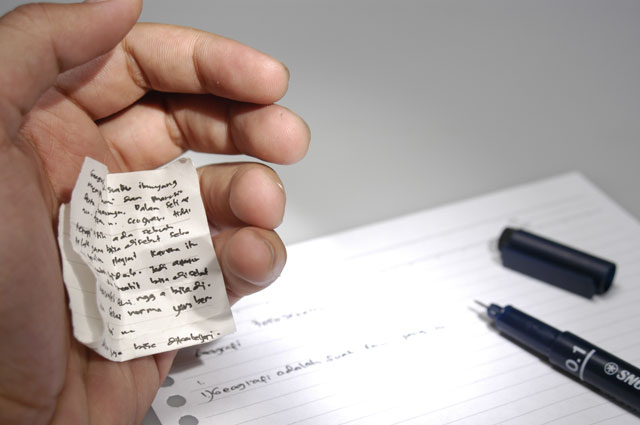

This isn’t fool proof. Students may still take the time to familiarise themselves with the contents of the documents they’ve bought so they can answer questions without exposing their dishonesty.

At the conference, some academics suggested that students should write assignments on templates supplied by their university which will track when work is undertaken and when it’s incorporated into the document. However, this sort of remedy is still being developed.

There is another problem with calling on academics alone to tackle plagiarism. Research suggests that many may themselves be guilty of the same offence or may ignore their students’ dishonesty because they feel investigating plagiarism takes too much time.

It has also been proved that cheating behaviour thrives in environments where there are few or no consequences. But perhaps herein lies a solution that could help in addressing the problem of plagiarism and paper mills.

Universities exist to advance thought leadership and moral development in society. As such, their academics must be role models and must promote ethical behaviour within the academy. There should be a zero tolerance policy for academics who cheat. Extensive instruction should be provided to students about the pitfalls of cheating and they must be taught techniques to improve their academic writing skills.

Universities must develop a culture of integrity and maintain this through ongoing dialogue about the values on which academia is based. They also need to develop institutional moral responsibility by really examining how student cheating is dealt with, confronting academics’ resistance to reporting and dealing with such cheating, and taking a tough stand on student teaching.

If this is done well then institutional values will become internalised and practised as the norm. Developing such cultures requires determined leadership at senior university levels.![]()

- Adele Thomas is professor of management at the University of Johannesburg

- This article was originally published on The Conversation