An electricity supply crisis is looming in South Africa that could make intermittent outages in the past few months seem trivial by comparison.

An electricity supply crisis is looming in South Africa that could make intermittent outages in the past few months seem trivial by comparison.

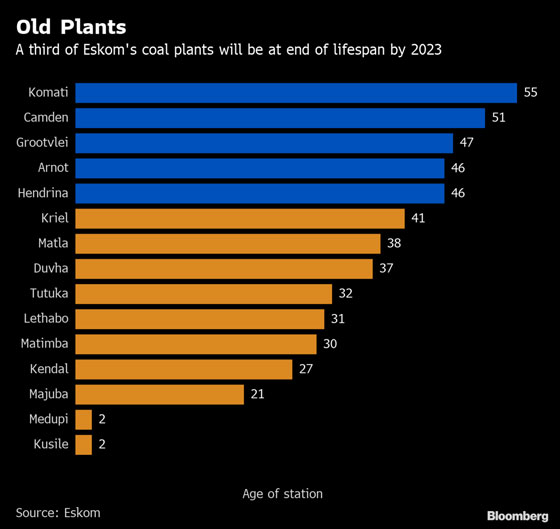

Eskom, which supplies almost all the nation’s power, will lose more than a quarter of its current generating capacity over the next decade as it shuts aging coal-fired plants. Replacing that output and adding capacity needed to meet rising demand will take years and cost more than R1-trillion rand, according to government estimates. The problem is likely to worsen exponentially after 2030 as more plants reach retirement age.

While Eskom is building two new plants, Medupi and Kusile, they are running years behind schedule and billions of rand over budget, and won’t be enough to plug the supply gap. The utility has limited scope to invest in more projects because it isn’t making enough money to cover its operating costs and service its debt, which had ballooned to R419-billion at the end of its last financial year.

The government has said it will look to private investors to help fund new plants and step up purchases of renewable energy from independent producers, which have added 3.9GW of capacity to the national grid since 2011. However, those plans are being implemented too slowly and on an insufficient scale, according to Jesse Burton, a researcher at the University of Cape Town’s Energy Research Centre.

“There’s this inaction by the state,” Burton said by phone. “We should be procuring immediately.”

President Cyril Ramaphosa in February announced plans to split Eskom into generation, transmission and distribution units — a move that should make it easier for private power producers to access the grid and sell their output. But powerful labor unions have vowed to prevent a break-up, fearing it will lead to job losses and privatisation. With elections due next month, the government has been loath to confront them head-on.

Integrated Resource Plan

Eskom has said its immediate focus will be to keep blackouts to a minimum by addressing maintenance backlogs, securing enough diesel to run turbines used at times of peak-power demand and fixing defects at its new units.

Beyond that, the nation’s energy blueprint, the Integrated Resource Plan, will spell out how future generation requirements will be met, according to public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan, who oversees Eskom. While the plan has been years in the making, it’s yet to be completed.

The document was significantly revised after the government determined that proposals favoured by former President Jacob Zuma to build nuclear plants weren’t affordable. The latest draft envisions the nation’s total installed power capacity rising about 60% to 78.3GW by 2030, with the bulk of the new supply coming from gas, solar power and wind.

Engie SA, which operates the 100MW Kathu concentrated solar power project 600km southwest of Pretoria and feeds into the grid, is among power companies that are awaiting the finalisation of the IRP and the issuing of new power supply tenders.

“We were surprised that the programme of development keeps delaying,” Paulo Almirante, the company’s chief operating officer, said in an interview at the plant. “Sometimes it’s a bit frustrating, the delays, but we are confident that after the elections this will be clarified and that the sector will continue to develop.” — Reported by Paul Burkhardt and Mike Cohen, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP