“South Africa is fortunate to boast excellence in a large number of cutting-edge science and technology domains. Whether it is in nanotechnology or astronomy, laser technology or high-performance computing, South Africa has made an impact in the global science area.” — Science & technology minister Naledi Pandor, February 2015

Pandor’s speech to the American Association for the Advancement of Science is helpful and honest, although perhaps a little one-sided. Science is not just about nanotechnology, medicine, astronomy and IT. It is about all of those research and discovery areas — and about climate change in the Antarctic, the diseases that kill forests and crops, and the study of the micro-organisms critical to life.

But science, as knowing, and so about knowledge, also embraces the human and social sciences — psychology, economics, history and languages among others. In these areas, South African scientists and scholars make substantial contributions to local, regional and international knowledge that is important for both science and society.

South African scientists are asking and helping answer critical questions. These include:

- How has the use of space and architecture shaped South Africa’s cities and contributed to the serious challenge of xenophobia?

- What is the role of capital cities in influencing local government and socioeconomic conditions?

- Why are we still measuring economic well-being by using GDP statistics when they are clearly a mis-measure of well-being?

South Africa is also undertaking pioneering work with regard to Mapungubwe’s history, and providing the world with data from the Southern African Large Telescope while developing, with fellow African countries, the massive Square Kilometre Array telescope — due to start producing information in 2020.

South African scientists are also contributing to the means for dealing with Africa’s single greatest killer — malaria.

South African scientists and scholars produce the most significant portion of Africa’s recognised research publications and, increasingly, doctoral students. More than 50 000 publications were produced between 2000 and 2010. This represents less than 1% of the world’s production of research papers — produced in South Africa’s case by just fewer than 20 000 researchers — but stands at 30% of Africa’s research output.

An important new trend has begun to develop — the growth of postgraduate students from the rest of the continent. In 2012, 4 698 PhD students (34%) in South African universities came from outside South Africa — a figure that has grown by 14% over a 12-year period. This has led some researchers to suggest that South Africa has the potential to become a “doctoral” hub for the continent.

South Africa has a long history of producing world-class research, especially in fields such as palaeontology and agriculture. During the academic boycott under apartheid, research contact with the rest of the world diminished. But steps taken since then have turned the situation around.

Re-joining the global world of science has led to quite dramatic changes in the research landscape. Most importantly, research output measured in terms of research papers published, and masters and PhD graduates, increased almost three-fold between the mid-1990s and 2013.

Data released in April highlight the areas of scientific research in which South Africa now excels when measured against the best institutions in the world.

Across the spectrum of the natural, social and human sciences, South Africa is well represented among the world’s best regarded institutions. The higher points of the landscape are the 10 South African scholars who are rated as being in the top 1% of the researchers across the world in their fields. These include academics in the environmental, social, biological and paleo-anthropological sciences.

Missing pieces of the puzzle

Despite the critical role science plays in positioning South Africa in the world of research, department of higher education & training support for universities has been declining. The rand values of departmental funding for universities have been rising but at lower rates than inflation and the needs of students.

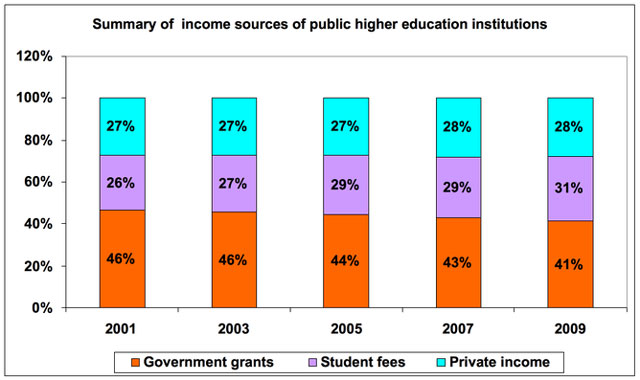

As a result, the proportional share of public funding for universities has been shrinking. Based on the latest available comparable data (for 2009) the following pattern emerges:

Over an eight-year period, public funding for universities dropped from 48% to 41% — and has continued to drop. Meanwhile, student fees have gone from a contribution of 26% to 31% of university income — which casts some light on student protests over fees.

The National Research Foundation (NRF) has taken steps to support researchers and graduate students as they work to add to South Africa’s scientific and scholarly knowledge. The NRF’s major contributions have been through the South African Research Chair Initiative, the creation of Centres of Excellence and support for the Academy of Science of South Africa and the South African Journal of Science.

Bear in mind that in the late 1980s, public funding for universities (and “technikons”, as they were then) constituted anything from slightly more than 50% to 70% of institutional income. This left some institutions in considerably constrained circumstances.

It also remains true that research production is still dominated by (aging) white men. This is a problem not just of equity but of forward planning. Women and black scientists and scholars remain minorities, especially at the professorial and senior research levels.

However, changes are beginning to take effect and most universities are deeply aware of the need for a socially equitable research landscape. This is certainly the case for major funding sources for research, which have been foregrounding the need for change that will secure South Africa’s growing productivity and stature in the wider world of science.![]()

- John Butler-Adam is consultant, vice principal for research and graduate education at the University of Pretoria

- This article was originally published on The Conversation