Online marketplaces, also known as platform companies, are sprouting up everywhere and redefining business in every industry. “The Uber of…” has become shorthand for tech start-ups looking to redefine the way everything is delivered, from legal services (Sydney-based LawPath) to Package deliveries (San Francisco-based Doorman), to Lottery services (Gibraltar-based Lottoland).

Paris-based Videdressing offers global aftermarket luxury branded fashion and Los Angeles-based DogVacay is an Airbnb-style online marketplace for dog vacations that has created a network of more than 20 000 pet sitters. It has raised more than US$45m from investors.

Major online marketplaces are attracting the attention of leading technology investors. Last year, Sydney-based Expert360, a global marketplace for consulting talent, attracted A$4m; Artsy, a New York-based global marketplace for artwork, closed US$25m, and Shyp, a San Franscisco-based on-demand shipping services marketplace finalised another $50m in investment.

There are currently 5 723 early-stage private online marketplace companies listed on AngelList, the leading online marketplace for investors in early stage technology start-ups. The average valuation is US$4,5m — so that is about $25bn worth of early stage start-ups in this area.

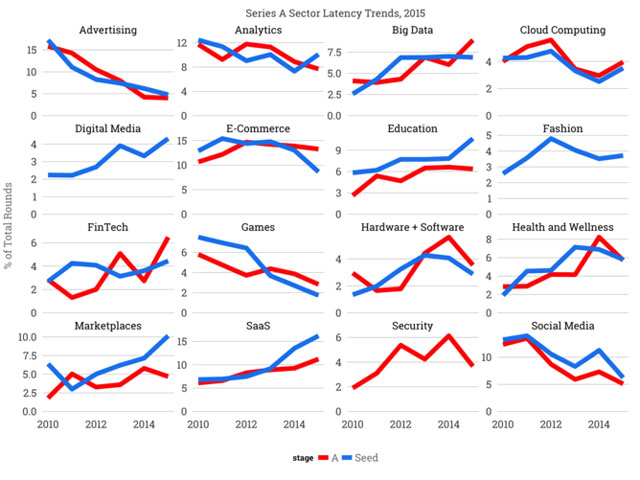

The US Center for Global Enterprise this year valued the global market for online platform-based companies at $4,3 trillion. Leading investors in the technology sector have also predicted online marketplaces and the related software-as-a-service (Saas) companies will be the hottest areas to invest in 2016.

The reason digital marketplaces are so valuable and sought after by investors is they tend toward a winner takes most equilibrium state.

The evolution of marketplaces

Great software used to be created by “hackers” or maverick programmers with a can-do spirit who toiled away in their bedrooms or university dorms to create revolutionary new applications, games and tools. Bill Gates, Steve Wozniak and Mark Zuckerberg are often cast in this role. This is not dissimilar to the modern idea of the architect — the solo iconoclast of Le Corbusier, Jørn Utzon or Frank Gehry who designed the last century’s most memorable buildings and then carefully directed others on every aspect of their construction.

But what if you could create a building more like a beehive — without a complete detailed design plan but instead agreement on principles and a set of rules of exchange, or in other words, using a market.

In his classic and influential essay and later book, The Cathedral and Bazaar, Eric Raymond contrasts two methods of developing software — one the “Cathedral” method where a small elite group of developers work on the software, versus the “Babbling Bazaar” approach pioneered by Linus Torvalds who led the formation of Linux, the open-source software system that today powers most of the Web.

Torvalds demonstrated how great and complex products like a computer operating system could incorporate many people’s diverse ideas. This could be done by using the Web as an organising force and a variety of tools to enable systematic incorporation of their labour. Wikipedia is a similar example of a “great cathedral” built with decentralised authority and a series of marketplace rules.

Where to next — Alchemy marketplaces

After two generations of online services marketplaces, we’re now entering a third, what I call Alchemy marketplaces.

The first generation of online services provided Advice marketplaces (forums for review and recommendations such as restaurant review websites and investment discussion boards). A second generation of services enabled Access marketplaces to transact online (such as registering domain names, buying shares or applying for jobs online); and now we’re seeing a third generation of services I call Alchemy marketplaces that combine networks, workflows with real world people and things such as transport (Uber); accommodation (Airbnb) and work (Freelancer.com).

In these sophisticated and often global third-generation marketplaces, a number of new trends are beginning to emerge, including formation of satellite businesses, support for agents and matrix-like automation support for third parties.

Once online marketplaces are established and begin to mature, we are seeing aggregation within the marketplaces themselves. Markets that started by connecting individuals to each other are evolving. For example, we are seeing Airbnb landlords who own multiple properties with a team of professional staff using the service to let their properties to tenants.

Flatbook, a company based in Canada, offers a booking service that works across hotels and Airbnb properties. It communicates with users from all stages, from taking bookings to explaining where the keys are, all via live chat often from the other side of the Atlantic.

New business models are emerging for companies servicing those in the marketplace itself. Uber started with individual drivers but now there are companies buying and leasing cars to drivers.

Indeed, a whole network of smaller specialist companies are emerging around many of these marketplaces. eBay started connecting a bunch of individuals selling second-hand goods to one another whereas today it’s mainly used by small businesses.

Many online marketplaces are providing support for agents — tools for small companies or freelancers to use their services to help their clients.

The complexity and quality of services that are able to be created on platforms will expand as more markets are built on top of other platforms and services

Some online services start out as consumer facing and then switch to serving businesses. Sequoia Capital-backed TokBox started out providing real-time video connections between individuals. It was a pioneer in being able to create Internet-based multi-person video chats before Skype and Google offered similar services. Then it changed its business model or “pivoted” to provide services to other companies that wanted to offer video services to their customers — it migrated effectively from being a retailer to becoming a wholesaler.

And many direct-to-consumer online marketplaces now also provide a facility for companies to create and on sell these services to their customers. Global online newsletter company Campaign Monitor, for example, provides “white label” services to enable small digital advertising agencies and graphic design firms to use their services and provide these to their clients.

Others are partnering with third parties to enable a mix of online services with offline partners. The university student jobs marketplace Ribit.net partnered with Australian fintech hub Stone and Chalk to help match university students with their resident start-up companies.

And some are complementing their large automated self-service marketplaces with live and real helpers: the global online services giant Freelancer.com recently introduced a new “recruitment service” that offers a human agent to help you find the perfect freelancer to match your needs.

Melbourne, Australia-based Marketplacer is a leading company focused solely on making marketplaces. It has created a platform for creating other platforms. Marketplacer has now founded seven marketplaces, including BikeExchange, which is the world’s biggest marketplace for everything bicycle related.

And in a kind of a back-to-the-future development, one of the hottest new online marketplaces is not a marketplace for jobs but one for for finding human recruiters — RecruitLoop.

Many online marketplaces now allow others to build new online systems that plug directly into theirs and build on top of them with an application programming interface, or API. This is hugely powerful and will have serious implications for many industries and companies.

Many platform and marketplace companies refer to this as cultivation of their “ecosystem” — a dynamic mixture of business partners and developers that has long been part of the software industry but is now extending into all industries.

A good example is online accounting software company Xero which has partnered with banks such as NAB to expedite loan approvals. It does this by sharing Xero customer accounting information online. There’s also a range of start-up companies like Vistr that offer cash flow forecasting services. Vistr is built on top of Xero so it means existing users can use it without re-keying any data.

Increasingly, as online marketplaces evolve, we’ll see more of this behaviour. The complexity and quality of services that are able to be created on platforms will expand as more markets are built on top of other platforms and services.![]()

- Paul X McCarthy is author of Online Gravity and adjunct professor, UNSW Australia

- This article was originally published on The Conversation