Who would have thought the Covid-19 pandemic would present a potential gold mine for companies specialising in the harvesting and selling of data?

Who would have thought the Covid-19 pandemic would present a potential gold mine for companies specialising in the harvesting and selling of data?

Apple’s market cap, now US$2.6-trillion, is up 136% since the onset of Covid. If it were a country, Apple would be the eighth largest in the world, just after France and India, with GDPs of $2.8-trillion and $2.7-trillion respectively.

Microsoft’s market cap, at $2.5-trillion, is up 116% since the onset of Covid. Google holding company Alphabet’s market cap is $1.9-trillion, up 138% over the same period. Facebook’s market capitalisation is up 135% to $853-billion since the Covid crash of March 2020, and is now the world’s seventh most valuable company.

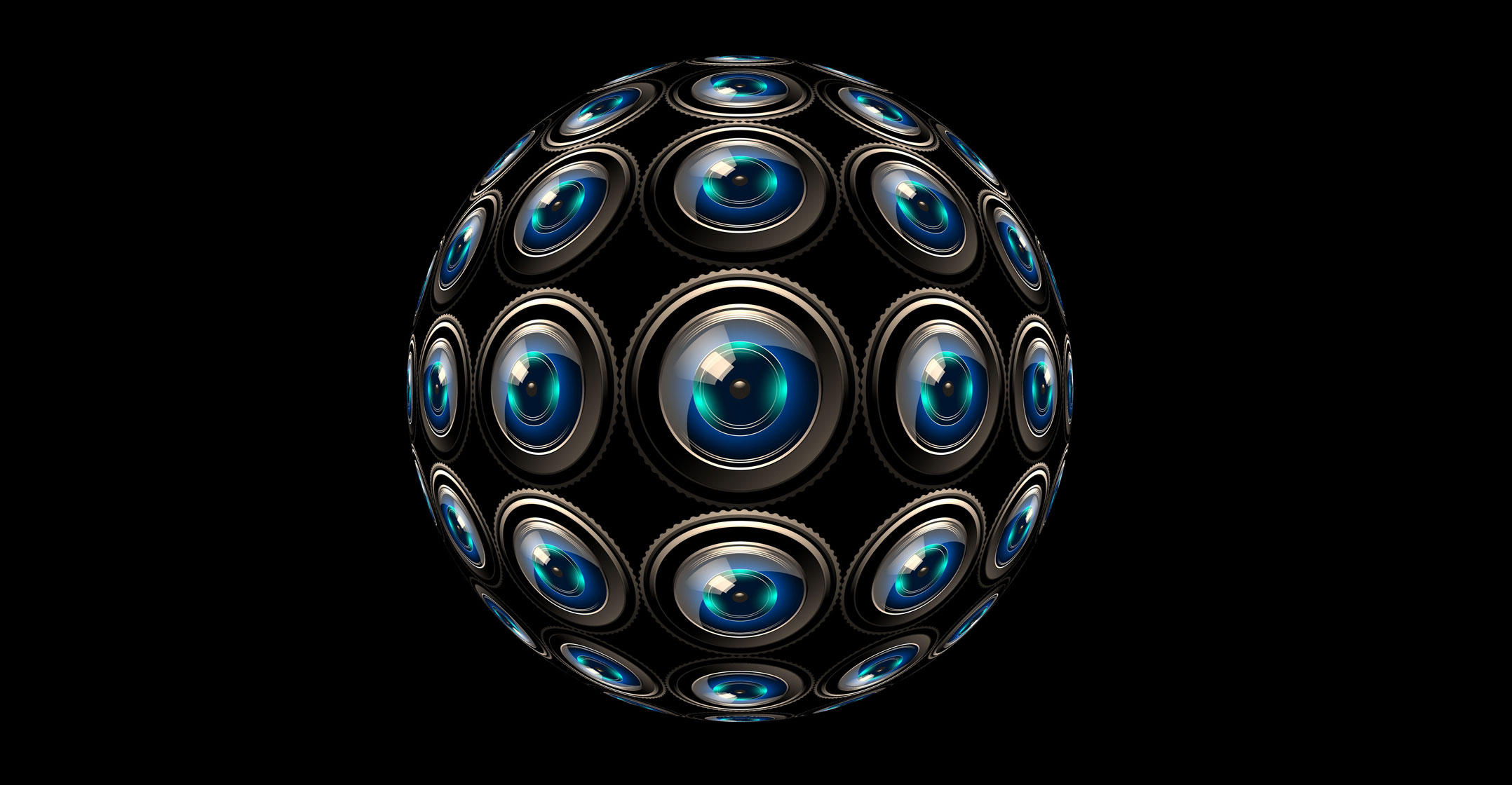

Data is the “new oil” and books like Life After Google by George Gilder and The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff explain how these tech companies have become the richest companies in the world by harvesting our personal data and selling it to advertisers and others.

A new report by research organisation Open Secrets called “Digital Profiteers – Who profits from social grants?” explains how the Covid pandemic created yet new opportunities for profit by tech companies as people migrated to an online world for shopping, information and health-care services.

It’s not as if South Africans haven’t been exposed to the uglier side of data harvesting before.

In 2012, grants agency Sassa contracted with Cash Paymaster Services (CPS) to handle social welfare payments. Under the banner of “financial inclusion”, CPS embarked on a massive enrolment drive, collecting data on 17 million beneficiaries and opening bank accounts for 10 million grant recipients.

CPS’s parent company, Net 1 UEPS Technologies, had unrestricted access to this database and used its subsidiaries to sell financial products to grant recipients.

It made more money from selling financial products than from distributing grants.

The constitutional court found the Sassa contract unlawful and ordered CPS to repay unlawful profits reckoned to be more than R500-million.

In April 2021, the top court ordered CPS, which has been fighting the case, to open its books to independent scrutiny to determine how much it must pay back.

Here we go again?

Which brings us back to the latest campaign to sign up millions of South Africans for Covid grant relief, which started in April 2020.

It was at this point that Open Secrets started to question the digitalisation of the welfare state. Its latest report focuses on GovChat, a relatively small South African technology company, though Sassa’s most visible partner in its digitalisation drive.

In early 2020, GovChat offered its services for free to set up a WhatsApp platform for the Covid-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant application process.

An SRD grant was made available to alleviate poverty and unemployment, and was awarded to seven million people from 12 million applicants between April 2020 and April 2021. The grant was reinstated in August 2021, and this time was awarded to eight million people from 13 million applicants.

“Globally, there has been inadequate scrutiny of how companies are profiting from their access to personal data gathered through government contracts under the auspices of providing public services,” says Open Secrets.

Though no claim of wrongdoing on the part of GovChat is made, Open Secrets says a fully automated grant application process presents an extraordinary opportunity to build a database of about half the country’s population, if one considers the existing 18 million grants paid by Sassa to 11 million beneficiaries, plus the 13 million applicants for SRD grants.

Though no claim of wrongdoing on the part of GovChat is made, Open Secrets says a fully automated grant application process presents an extraordinary opportunity to build a database of about half the country’s population, if one considers the existing 18 million grants paid by Sassa to 11 million beneficiaries, plus the 13 million applicants for SRD grants.

“The plan to digitise has opened up the possibility that this data will be available to a variety of public and private actors.

“Access to the data of more than 30 million people would constitute the kind of big ‘data play’ that financial and technology firms dream of,” says Open Secrets.

The report’s author, Michael Marchant, when asked whether GovChat, which Open Secrets admits has not been found guilty of any wrongdoing, is being “pre-crimed”, as in the film Minority Report where the police use clairvoyants to detect crimes before they happen, said: “It’s a valid question, but I think it is equally valid to draw attention to the potential for abuse and hopefully get some discussion going around ownership of our private data, which is protected under the Protection of Personal Information Act (Popia), who gathers this information and how it is monetised.”

The plan to digitise has opened up the possibility that this data will be available to a variety of public and private actors

Open Secrets says GovChat may have provided its services to Sassa for free in a time of need, but that puts it in an ideal position to benefit from future contracts linked to the distribution of social assistance.

It says “it is apparent that GovChat has been granted a significant advantage without the normal legal requirement of a competitive procurement process, and the public scrutiny that such a process provides”.

Perhaps understandably, GovChat has taken offence to the association with Net1 and CPS.

Eldrid Jordaan, CEO of Govchat.org, responds that any party that engages with government should be subject to reasonable level of scrutiny and should conduct itself in accordance with all appropriate laws and regulations.

“Our objection was not to the scrutiny, as we have nothing to hide and the Open Secrets report and their reporters have admitted that they have found no impropriety at GovChat.

‘Innuendo and inferences’

“Our objection lies in the innuendo and the inferences the report makes by reference to Net1 and CPS, entities and organisations that have been judicially determined to have acted inappropriately.”

GovChat received R20-million in equity funding for a 35% share from JSE-listed fintech Capital Appreciation (Capprec), which in turn counts African Rainbow Capital among its shareholders.

Capprec in turn owns three subsidiaries – Synthesis, African Resonance and Dashpay – all of which are focused on selling technological solutions to financial and banking clients.

Another aspect to the case involves the Competition Tribunal, which last month extended a March order interdicting Facebook (owner of WhatsApp) from kicking GovChat off the messaging app.

Facebook had argued that GovChat was violating its terms of service and was able to aggregate data without checks and balances, giving it an unfair advantage over other business solutions providers.

GovChat argued that to off-board it from WhatsApp would materially prejudice its business.

GovChat argued that to off-board it from WhatsApp would materially prejudice its business.

Says Jordaan: “[Regarding] the Competition Tribunal’s decision, it is a decision which extends its prior determination and allows the Competition Commission’s inquiry into WhatsApp’s anticompetitive conduct to be completed. We are hopeful that the Competition Commission will conclude that WhatsApp’s conduct is anticompetitive and refer the matter to the tribunal for full adjudication.”

Open Secrets points out that Facebook has been found to violate users’ privacy and sell their data without consent – the most recent case earning it a R4-billion fine by Irish authorities for violating the EU’s data privacy laws. Facebook’s response to tighter regulatory scrutiny has been to throw money at lawmakers “and push back against more effective regulation”, says the report.

“Given this track record, Facebook’s appetite for contracts with South African government departments and private-sector actors to hoover up more data must be watched closely by regulators and civil society. Open Secrets will certainly be doing so.”

- This article was originally published by Moneyweb and is republished by TechCentral with permission