Why aren’t there more female software developers in Silicon Valley? James Damore, the Google engineer fired for criticising the company’s diversity programme, believes that it’s all about “innate dispositional differences” that leave women trailing men.

He’s wrong. In fact, at the dawn of the computing revolution, women, not men, dominated software programming. The story of how software became reconstructed as a guy’s job makes clear that the scarcity of female programmers today has nothing at all to do with biology.

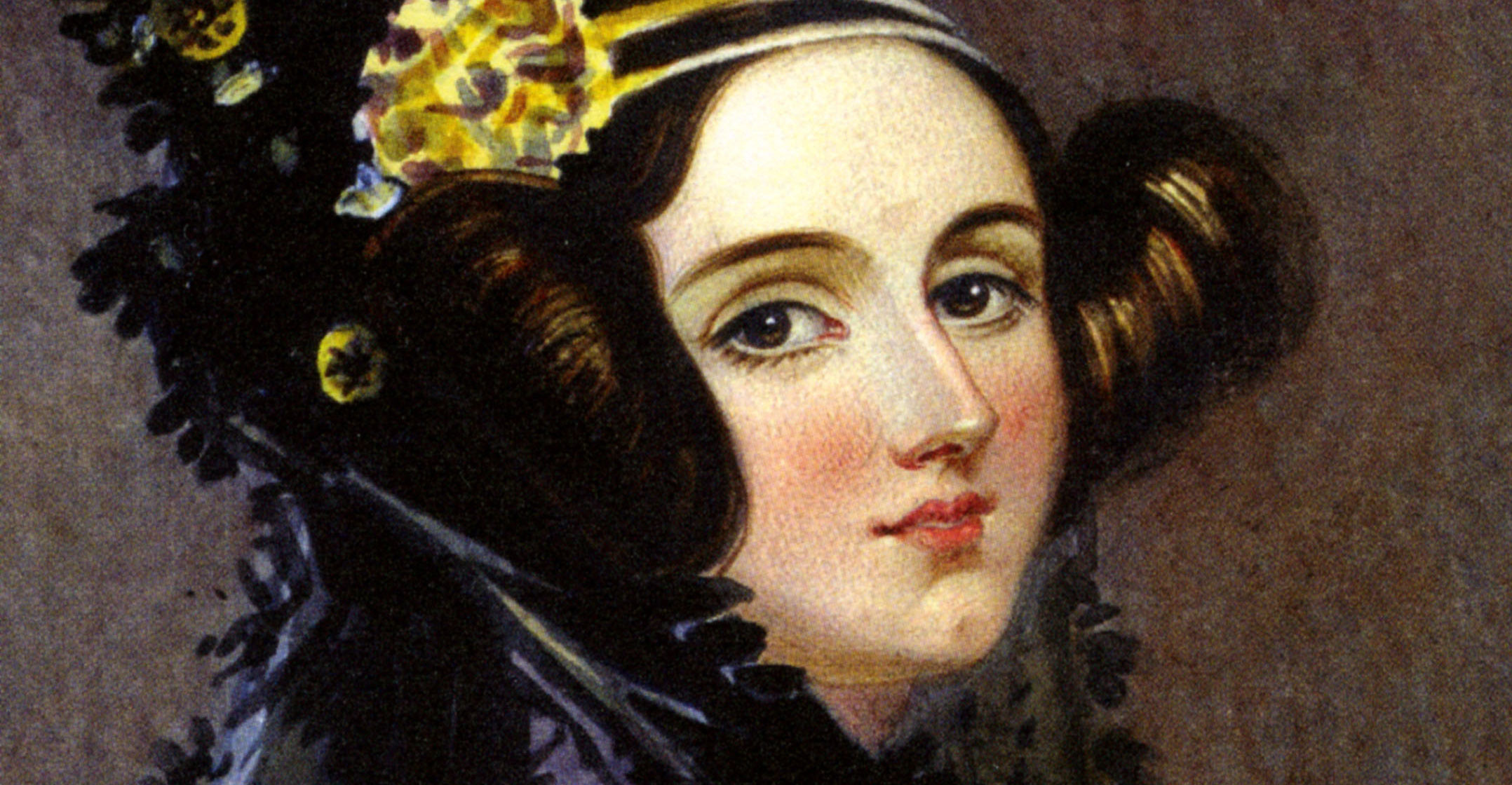

Who wrote the first bit of computer code? That honour arguably belongs to Ada Lovelace, the controversial daughter of the poet Lord Byron. When the English mathematician Charles Babbage designed a forerunner of the modern computer that he dubbed an “analytical engine”, Lovelace recognised that the all-powerful machine could do more than calculate; it could be programmed to run a self-contained series of actions, with the results of each step determining the next step. Her notes on this are widely considered to be the first computer program.

This division of labour — the man in charge of the hardware, the woman playing with software — remained the norm for the founding generation of real computers. In 1943, an all-male team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania began building Eniac, the first general-purpose computer in the US. When it came time to hire programmers, they selected six people, all women. Men worked with machines; women programmed them.

“We didn’t think we should spend our time worrying about figuring out programming methods,” one of Eniac’s architects later recalled. “There would be time enough to worry about those things later.” It fell to the women to worry about them, and this original team of women made many signal contributions, effectively inventing the field of computer programming. But programming had no cachet or notoriety; it certainly wasn’t seen as inspiring work, as historian Janet Abbate’s account of this era makes clear.

Stereotypes

Sexist stereotypes are used today to justify not hiring women programmers, but in the early years of the computer revolution, it was precisely the opposite — and not without the encouragement of women as well. Early managers became convinced that women alone had the skills to succeed as programmers. Still, it was considered glorified clerical work.

For example, a female editor at Datamation, a computer magazine, noted that personnel managers in 1963 believed that “women have greater patience than men and are better at details, two prerequisites for the allegedly successful programmer”. Better yet, this article claimed, “women are less aggressive and more content in one position”. At the time, turnover among programmers averaged 20%/year, so the idea of a compliant force of female programmers seemed like a winning solution to staffing problems.

Even Helen Gurley Brown’s Cosmopolitan endorsed programming as a career. In 1968, it published “The Computer Girls”, an article that hailed computers as an area where “sex discrimination in hiring” didn’t happen because employers actually preferred women. “Every company that makes or uses computers hires women to program them,” the magazine declared, though it quickly reverted to form, telling readers that female programmers found it easy to get dates because the field was “overrun with males”.

In fact, men had began to recognise that programming was the most important job in the new information economy. In order to elevate the importance of their work, the first generation of male programmers began crafting a professional identity that effectively excluded women. As historian Nathan Ensmenger has observed, “computer programming was gradually and deliberately transformed into a high-status, scientific, and masculine discipline”.

The now-familiar stereotype of the male programmer began to form at that time. Men from established fields like physics, mathematics and electrical engineering making the leap to a new one that had no professional identity, no professional organisations, and no means of screening potential members. They set out to elevate programming to a science.

By the mid-1960s, that led to the rising influence of professional societies for programmers, including the Association for Computing Machinery, or ACM. The leadership of these groups skewed heavily toward men, and they began building barriers to entry in the field that put women of this earlier era at a distinct disadvantage, particularly a requirement for advanced degrees.

In addition, growing numbers of companies eager to hire programmers began administering aptitude and personality tests to find the right employees. The tests proved next to useless in predicting whether a person made a good programmer. “In every case,” the ACM’s own authority on the subject wrote, the correlation between test scores and future performance “was not significantly different than zero”. But they remained in widespread use in most major corporations, and when men scored higher on these tests, they got the jobs, not women. In the process, the “computer boys”, as the press dubbed them, took over.

Pernicious

Even more pernicious was the creation of the now-familiar stereotype of the computer programmer as a reclusive, eccentric man with limited social skills. In the 1960s, two psychologists ran studies to try and figure out the personality traits that defined computer programmers. They found some predictable ones: a love of solving puzzles, for example. But the only “striking characteristic” that defined successful male programmers was “their disinterest in people”. A subsequent study — one that was overlooked in subsequent years — found this to be true of female programmers as well.

Instead, introverted men became the industry standard when it came to hiring programmers. In 1968, analyst Richard Brandon told the annual meeting of the ACM that the typical programmer was “excessively independent … often egocentric, slightly neurotic, and he borders upon a limited schizophrenia. The incidence of beards, sandals, and other symptoms of rugged individualism or nonconformity are notably greater among this demographic group.”

The creation of this stock figure became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the years passed, the idea that the best programmers were idiosyncratic, antisocial men became the norm. Computer programming, once associated with careful, meticulous women, now became the domain of iconoclastic men who lived by their own rules.

While companies seeking programmers had previously sought out women as well as men, by the late 1960s the pitch to potential employees had changed. Pretty typical was an advertisement that IBM ran in 1969. It asked potential programmers whether they had the qualities to cut it as a programmer. But what really stood out was the question emblazoned at the top of the advertisement: “Are YOU the man to command electronic giants?”

This bias remains alive and well. What’s ironic, though, is that it flies in the face of the history of computing. Women dominated programming at one time, but got pushed aside once men discovered the field’s importance. That messy history, not simple biology, accounts for the gender imbalance bedevilling Silicon Valley. — Written by Stephen Mihm, an associate professor of history at the University of Georgia, (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP