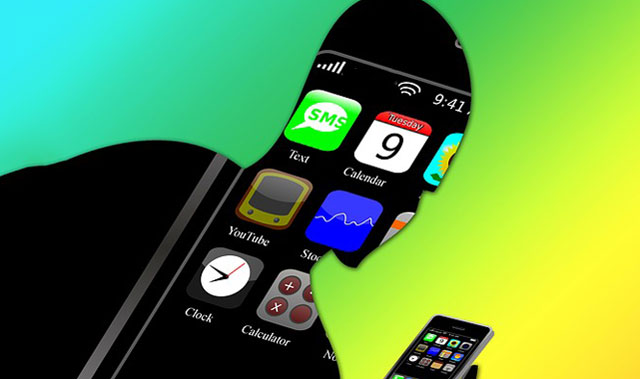

A common experience: you are walking down the street and someone is walking in the opposite direction toward you. You see him but he does not see you. He is texting or looking at his cellphone. He is distracted, trying to do two things at the same time, walking and communicating.

There is also the tell-tale recognition of a car driver on a phone; she’s driving either too slowly or too fast for the surrounding conditions, only partly connected to what is going on around her. Connected to someone else in another place, she is not present in the here and now.

These types of occurrences are now common enough that we can label our time as the age of distraction.

The age of distraction is dangerous. A recent report by the National Safety Council showed that walking while texting increases the risk of accidents. More than 11 000 people were injured last year while walking and talking on their phones.

Even more dangerous is the distracted car driver. Distracted drivers have more fluctuating speed, change lanes fewer times than is necessary and in general make driving for everyone less safe and less efficient.

Texting while driving in the US resulted in 16 000 additional road fatalities from 2001 to 2007. More than 21% of vehicle accidents are now attributable to drivers talking on cellphones and another 5% were text messaging.

Multitasking relatively complex functions, such as operating handheld devices to communicate while walking or driving, is not so much an efficient use of our time as a suboptimal use of our skills.

We are more efficient users of information when we concentrate on one task at a time. When we try to do more than one thing, we suffer from inattention blindness, which is failing to recognise other things, such as people walking toward us or other road users.

Multitaskers do worse on standard tests of pattern recognition and memory recall. In a now classic study, researchers at Stanford University found that multitaskers were less efficient because they were more susceptible to using irrelevant information and drawing on inappropriate memories.

Multitasking may not be all that good for you either. A 2010 survey of over 2 000 eight- to 12-year-old girls in the US and Canada found that media multitasking was associated with negative social indicators, while face-to-face contact was associated with more positive social indicators such as social success, feelings of normalcy and hours of sleep (vital for young people).

Although the causal mechanism has yet to be fully understood — that is, what causes what — the conclusion is that media multitasking is not a source of happiness.

There are a number of reasons behind this growing distraction.

One often-cited reason is the pressure of time. There is less time to accomplish all that we need to do. Multitasking then is the result of the pressure to do more things in the same limited time. But numerous studies point to the discretionary use of time among the more affluent, and especially more affluent men. The crunch of time varies by gender and class. And, paradoxically, it is less of an objective constraint for those who often articulate it most.

Although the time crunch is a reality, especially for many women and lower-income groups, the age of distraction is not simply a result of a time crunch. It may also reflect another form of being. We need to reconsider what it means to be human, not as continuous thought-bearing and task-completing beings but as distraction-seeking creatures that want to escape the bonds of the here-and-nowness with the constant allure of someone and somewhere else.

Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff asserts that our sense of time has been warped into a frenzied present tense of what he calls “digiphrenia”, the social media-created effect of being in multiple places and more than one self all at once.

There is also something sadder at work. The constant messaging, e-mailing and “cellphoning”, especially in public places, may be less about communicating with the people on the other end as about signalling to those around that you are so busy or so important, so connected, that you exist in more than just the here and now, clearly a diminished state of just being.

There’s greater status in being highly connected and constantly communicating. This may explain why many people speak so loudly on their cellphones in public places.

The age of distraction is so recent we have yet to fully grasp it. Sometimes art is a good mediator of the very new.

A video art installation by Siebren Verstag is entitled Neither There nor There. It consists of two screens. On one side a man sits looking at his phone; slowly his form loosens as pixels move to the adjacent screen and back again. The man’s form moves from screen to screen, in two places at one time but not fully in either.

One study that looked at the effect of banning cellphones in schools found that student achievement improved when cellphone were banned, with the greatest improvements accruing to lower-achieving students, who gained the equivalent of an additional hour of learning a week.

On many college campuses, faculty now have a closed-laptop policy after finding students would use their open laptops to skim their e-mails, surf the Web and distract their neighbours. This was confirmed by studies that showed that students with open laptops learned less and could recall less than students with their laptops closed.

We are witnessing a cultural shift occurring with the banning of devices, cellphone usage being curtailed in certain public places and policies banning texting while driving. This is reactive. We also need a new proactive civic etiquette so that the distracted walker, driver and talker have to navigate new codes of public behaviours.

Many coffee stores in Australia, for example, do not not allow people to order at the counter when they are on the cellphone, more golf clubs are banning the use of cellphones while on the course and it is illegal in 38 states in the US for novice drivers to use a cellphone while driving.

There is also the personal decision available to us all, one foreshadowed by writer and social critic Siegfried Kracauer, who lived from 1889 to 1966. In a newspaper article on the impact of modernity, first published in 1924, he complained of the constant stimulation, the advertising and the mass media that all conspired to create a “permanent receptivity” that prefigures our own predicament in a world of constant texting, messaging and cellphones.

One response, argued Kracauer, is to surrender yourself to the sofa and do nothing, in order to achieve a “kind of bliss that is almost unearthly.”

One radical response is to unplug and disconnect, live in the moment and concentrate on doing one important thing at a time. Try it for an hour, then for a day. You can even call your friends to tell them about your success — just not while walking or driving, or working on your computer screen or speaking loudly in a public place.![]()

- John Rennie Short is professor, school of public policy, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- This article was originally published on The Conversation