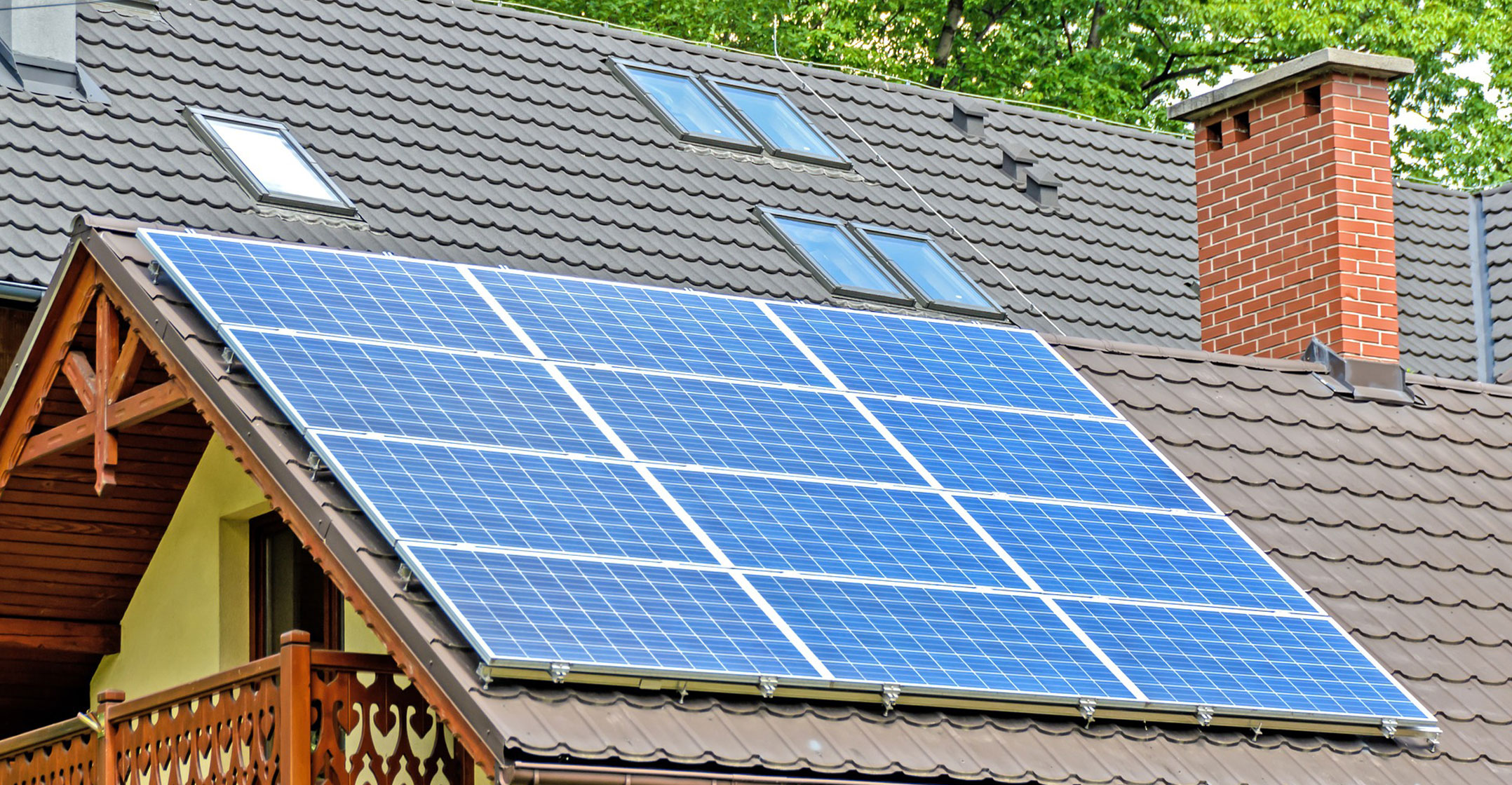

Eskom hopes its proposed retail tariffs for 2021 will help solve a looming problem triggered by increased solar generation across the country.

Eskom hopes its proposed retail tariffs for 2021 will help solve a looming problem triggered by increased solar generation across the country.

It cites a research study that projects between R3.5-billion and R4-billion in revenue will be lost to photovoltaic (PV) solar generation by the end of this year. Many would argue these numbers are on the low side.

The shift to solar generation by business and households has resulted in two major problems for Eskom.

First, it says “customers using PV systems during the day results in drop in the demand for electricity during the day – with the highest drop in system demand in the middle of the day. This midday demand drop (called the ‘duck curve’) affects the power system negatively, as it means that the generators have to ramp up at an even faster rate than before to meet the evening peak demand.”

As solar usage increases, so demand during the day will continue to decline, including a flattening of the morning peak. This causes an ever-increasing ramp up to the evening peak.

Lost revenue

Second, because existing tariffs are largely variable-usage based (charged per kilowatt-hour), Eskom argues that they do not adequately “reflect the fixed costs and also the demand a customer imposes on the network”.

As customers move to solar, Eskom contends they could become a “zero net or very low net” consumer as they feed excess power back into the grid during the day. Because they still use the network, this resultant “loss of revenue” will not be commensurate with a reduction in costs.

Eskom says “it also results in customers with PV being subsidised by customers without PV”. The utility argues that its current tariff structure has caused this.

This view is supported by the South African Local Government Association (Salga), which in its draft comments on the proposed tariffs says “the challenge is that current tariffs have sent incorrect tariff signals to end customers creating a falsely attractive business case for own generation”.

This view is supported by the South African Local Government Association (Salga), which in its draft comments on the proposed tariffs says “the challenge is that current tariffs have sent incorrect tariff signals to end customers creating a falsely attractive business case for own generation”.

Eskom is adamant that its proposed changes “must not be viewed as ‘anti-renewable’, but rather as an attempt to support the connection of alternative energy resources in a responsible way and to avoid unwarranted and non-economic cross-subsidies”.

It says the proposed changes will not “hamper the uptake of small-scale electricity generation” or households or larger consumers generating their own power, “but rather that more correct and economic signals are provided when making alternative energy choices”.

Aside from the rationalisation and simplification of its tariff plans, there are three major adjustments proposed by Eskom:

1. Changes to peak pricing

Eskom wants to change the peak versus standard versus off-peak periods as well as prices in its time-of-use (TOU) tariffs. It argues that “the current TOU charges last changed in 2005 and no longer reflect the current system and customer requirements”. Because 80% of its sales are on these tariffs, any distinctions between peak/off-peak and seasonality are critical.

It wants to increase the evening peak to three hours (from two) and decrease the morning peak to two hours (from three), introduce a “standard period” on a Sunday evening, and – importantly – change the ratios between summer (low demand) and winter pricing (higher demand).

The proposed structure will see the gap between peak as well as weekday day-time pricing narrow when comparing winter versus summer.

2. Removing the incline block tariff structure

2. Removing the incline block tariff structure

It proposes the removal of the incline block tariff (IBT) structure for residential customers it supplies directly (like greater Sandton and Soweto).

Consumers, particularly those on prepaid, are mostly confused by the incline block structure, where the more you use, the more you pay per unit of electricity.

Eskom says it is “very unpopular in community discussions” and that some “customers buy legally at the low block and then illegally once they reach the higher block consumption”.

At the higher end (Homepower), Eskom says “the use of inclining block tariffs greatly incentivises higher-consumption customers to use alternative energy sources and energy efficiency, resulting in a real revenue loss not commensurate with a real cost reduction”.

It stresses that the overall subsidy received by Homelight (for low-consumption households) does not change. However, within each of the residential tariffs (Homelight and Homepower), there are obvious impacts: “Lower-consumption customers will pay slightly more and higher-consumption customers less.”

3. New way of charging households that want to sell solar back to the grid

Eskom wants to introduce a new tariff, Homeflex, for urban residential customers (think wealthier households in, say, Bryanston). It will be mandatory for those who want to sell power back to the grid from their solar installations (and voluntary for any other residential customer).

In this tariff, Eskom notes “customers would need to pay for the required smart time-of-use meter”. No further details on the meter are provided, given this is a tariff application. Homeflex unbundles charges into energy and network charges (something done by City Power and many other metros).

It will pay the same rate for energy sold back to the grid that the tariff charges in its time-of-use breakdown. In other words, it will pay the winter daytime rate if you’re feeding back solar to the grid during that time. But customers will pay fixed network charges regardless of their power consumption.

All three of these changes will have wide ramifications for all users of electricity, even if they are not directly supplied by Eskom. Changes to peak pricing and time-of-use tariffs will filter through to municipal tariffs, even if these aren’t based on time of use.

Salga says “the rationale to remove the IBT tariff is plausible and supported”. Energy regulator Nersa “needs to make a decision on the sustainability of the IBT tariff so that the entire country can move in the same direction. Again, a transition plan will be needed to educate and inform customers of the proposed changes and the impact of the changes on their electricity bill.”

Raft of changes

If approved, Nersa will likely nudge (or force) municipalities away from incline block tariffs in future.

Eskom’s hefty 113-page submission to Nersa provides detailed motivation for a raft of proposed changes beyond those highlighted above. It says there has been consultation with the System Operator, Eskom divisions, the Energy Intensive Users Group and the Association of Municipal Electricity Utilities.

Nersa is expected to pronounce on the tariffs by March. These will be implemented from 1 April for Eskom-direct customers and on 1 July for municipalities that bulk-buy power from the utility.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission