The dust has now settled on the latest product launch from Apple, which for many trumped headlines about refugees and poverty. We have new iPads, iPhones and more. But how new are they really?

Innovation is often characterised as being either “radical” or “incremental”. When it is radical, it sets new precedents and fundamentally changes the way we do things. From self-administered insulin to solar-powered houses to driverless cars, radical innovation releases potential. Incremental innovation on the other hand builds upon what is already there in small steps.

In the world of mobile phones and tablets, incremental has become the new radical, and true radical innovation has been relegated to the sidelines. Incremental innovation has become the norm because of a belief that “slow and steady wins the race”, that people don’t like the risks that come with big dramatic changes. That seems to be Apple’s long-term strategy and, as a dominant player, it is setting the culture for other players in the market.

Using staged marketing in the form of annual or biannual high-profile media launches, tech firms have groomed us as consumers to accept small change as normal. More radical innovation, such as a modular phone that can be continually upgraded, is seen as crazy, quirky or even science fiction.

The new iPad Pro that is a few inches bigger than the last one is being hailed as a “big leap” when it’s really just tinkering with the old design. Despite the new features, it in no way represents a radical innovation worthy of ecstatic celebration. The whoops of delight at its launch were followed by voices of disappointment online.

It is primarily for commercial reasons that Apple has institutionalised incremental innovation and tried to convince us all it is radical. iPhones and iPads are brilliantly designed things. Incremental innovation requires expertise and excellence in design and improvement. Phones and tablets play a major part in millions of people’s lives. But continued innovation happens at a slow pace designed to suit the supplier not the user, who is nonetheless pushed to pay significant amounts of money each year for minor changes.

Fear of failure may have also contributed to the disappearance of radical innovation. The struggles of more unusual designs such as that of the Amazon Fire phone may have made innovators more cautious, delaying and lengthening product development and roll-out to compensate. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that virtually none of the radical (labelled “crazy” at the time) concept phones of 2010 have never appeared on the market.

We may have also reached a point where phone design is so good that truly impressive change has become much harder to achieve. So we continue to buy similar looking products, putting them to our ears (just as we did with landlines), snapping cameras with slightly better picture clarity, and getting slightly more intelligent answers from Siri. Same game, tiny changes, price hike.

At the same time, major new challenges are emerging for smartphone makers, from evidence that current phone designs may be fuelling unhappiness and reducing productivity to the worrying environmental impact of manufacturing them. Radical innovation is needed so that phones fully serve customer interests in a sustainable way.

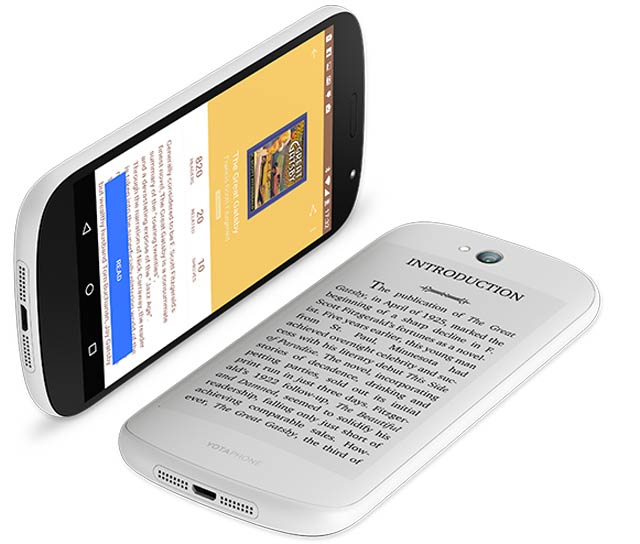

But for the time being, more radical products, such as the Yotaphone 2, (which offers a dual screen), or the Runcible (round, beautiful and rather different), will be at best seen as quirky and niche. The existing market leaders will only change their tortoise-speed approach to radical innovation if a major new player genuinely disrupts the market with fast, penetrative changes.

For example, Chinese company Xiaomi is creating a range of products for the home (from TVs to air purifiers) that automatically link with their smartphones in a single, integrated system. This is the kind of radical idea that could shock Apple into becoming more radical and adventurous.

We could eventually see mobile computing move away from handheld, screen-based devices towards seamless interaction across different devices and platforms such as wearable technology and projected holograms.

For the foreseeable future, however, innovation in the mobile and wearable space is going to be dominated by incremental and fairly mediocre approaches to innovation. Radical thinking will be consigned to concepts for the future and the iPhone 7 will probably look a lot like the iPhone 3. But the launch will be offered as another revolution.![]()

- Paul Levy is senior researcher in innovation management at the University of Brighton

- This article was originally published on The Conversation