The year was 1999. Steve Jobs had recently returned to lead Apple. Intel was the dominant force in semiconductors. And a little-known chip maker named Nvidia made its debut on the Nasdaq stock exchange.

It took less than three years for Nvidia to ascend into the S&P 500 — replacing the disgraced oil-trading conglomerate Enron, no less.

But even then, few people would have bet that the company would go on to become the best-performing stock of the last quarter century, posting a total return of 591 078% since its initial public offering, including reinvested dividends. It’s a difficult number to comprehend and a testament, in part, to the financial mania brewing around artificial intelligence and how investors have come to see Nvidia — which makes the cutting-edge chips powering the technology — as the single-biggest winner of the boom.

On Tuesday, that run culminated in Nvidia unseating Microsoft as the world’s most valuable company with a market capitalisation of $3.34-trillion.

The company’s rise was by no means assured — and neither is its staying power at the top of the S&P 500. Long-time investors in Nvidia have had to stomach three annual collapses of 50% or more in the stock. Sustaining the current rally will require customers to keep spending billions of dollars a quarter on AI equipment, whose returns on investment are so far relatively small.

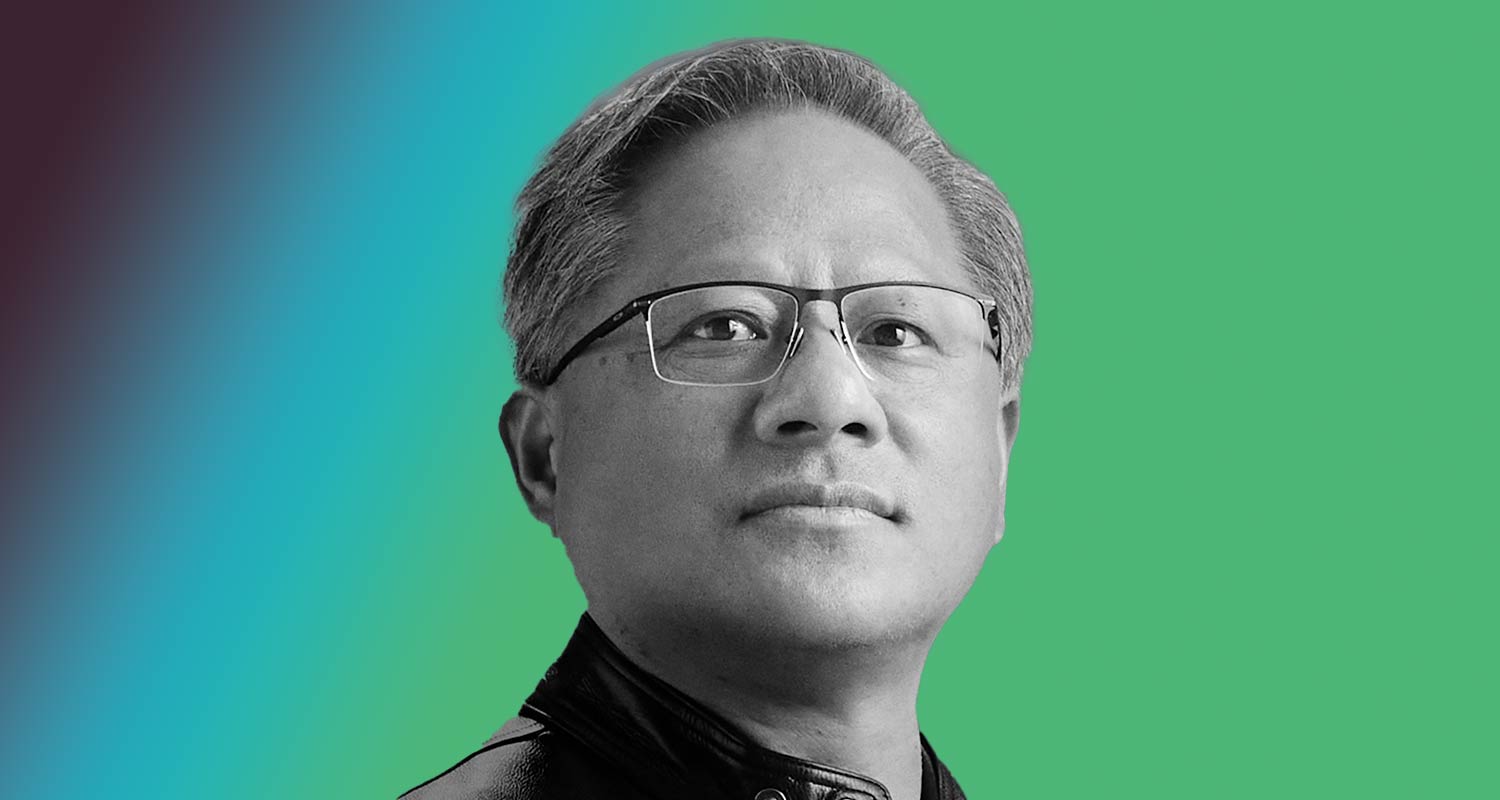

What ultimately paved the way for Nvidia to climb to the top, though, was the company’s big bet on graphics chips and the vision of co-founder and CEO Jensen Huang that the industry would shift to what he calls “accelerated computing”, something his chips are inherently better at than the competition.

“You have to give the management team, I think, an enormous amount of credit,” said Brian Mulberry, client portfolio manager at Zacks Investment Management. “They have caught each wave of innovation in hardware perfectly well.”

Here’s a look at Nvidia from its 1999 listing to now.

The early years

Nvidia got off to a hot start. Between its debut and entering the S&P 500, Nvidia had gained more than 1 600%, giving it a market value of about $8-billion. That rise came as many other technology stocks were cratering in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble, which peaked in March 2000.

The company’s key to early success: getting its technology in videogame consoles like Microsoft’s Xbox and Sony’s PlayStation. Nvidia’s GeForce graphics processing units, or GPUs, became objects of desire among gamers because they consistently offered the most realistic experience.

“Jensen was always a great communicator, told a good story, and clearly GPUs were becoming more important,” said Rhys Williams, chief strategist at Wayve Capital Management, who was a buyer in the IPO. “Each successive generation of hardware gave a lot better performance, a lot more realistic picture and then PC gaming really came into being.”

Litigation and competition

The next six years weren’t kind to Nvidia. The stock plunged in 2008 as the financial crisis weakened demand and long-struggling rival AMD started upping its game.

Meanwhile, an agreement between Nvidia and Intel that allowed the companies to use each other’s capabilities went sour, forcing Nvidia out of one of its biggest markets. The two settled in 2011, with Intel agreeing to pay Nvidia $1.5-billion.

The following year, Nvidia unveiled graphics chips for servers inside data centres. They could help sophisticated computing work such as oil and gas exploration and weather prediction, giving Nvidia a foothold in what would become a lucrative market. However, those chips did not immediately fly off the shelf. It would take nearly nine years for Nvidia shares to surpass their 2007 high.

Crypto and Covid

Crypto and Covid

Nvidia shares were taking off again in 2015. During that period, Nvidia chips were becoming the foundation of emerging technologies, from advanced graphics interfaces to autonomous vehicles to a new wave of AI products.

That’s when Shana Sissel, CEO at Banrion Capital Management, first really took note of the company. She described a 2017 conference where Nvidia was more like a pageant winner than an investment idea.

“Every single speaker talked about Nvidia being the most important company,” Sissel said. “At that point, it was really on my radar screen.”

Even after demand from cryptocurrency miners dried up, data centre sales continued to grow. The Covid-19 pandemic boosted that business, as companies needed to purchase additional computing power to support remote work. Nvidia’s data centre revenue rose by a multiple of eight from fiscal 2017 to fiscal 2021.

AI sales explode

Nvidia’s shares slumped in 2022 along with the rest of the technology sector, which was reeling from soaring interest rates and falling demand after the Covid-era boom.

OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT in late 2022 made an instant splash but it took time for investors to realise how Nvidia might benefit. Eventually, an explosion of interest in generative AI products including ChatGPT sent orders for Nvidia’s chips through the roof.

The scale shocked nearly everyone in May 2023 when Nvidia’s results beat even the most optimistic Wall Street estimates. The company gave a forecast for quarterly sales that was more than 50% above the average projection.

Nvidia’s data centre sales eclipsed its gaming revenue for the first time in fiscal 2023. In Nvidia’s current fiscal year, which ends in January, analysts expect those sales to top $100-billion.

“They have a very defensible place in the industry,” said Williams. “They’re not going to be 95% of market share forever, obviously, but it would be almost impossible for anybody to replace them.” — Jeran Wittenstein and Carmen Reinicke, with Ian King, (c) 2024 Bloomberg LP