A South African technology firm, Cirrus Water Management, is helping pioneer a technology known as atmospheric water generation, or AWG — in effect, it’s “squeezing” water out of thin air.

Commercial director Bruce Jones, a civil engineer by training who has worked for software vendors SAP and SAS Institute, explains that he joined Cirrus Water’s Mike Murray, who had been working for five years on an AWG solution for the South African market, to commercialise the offering.

He says that although the technology is in the public domain, only a handful of companies worldwide are pursuing it.

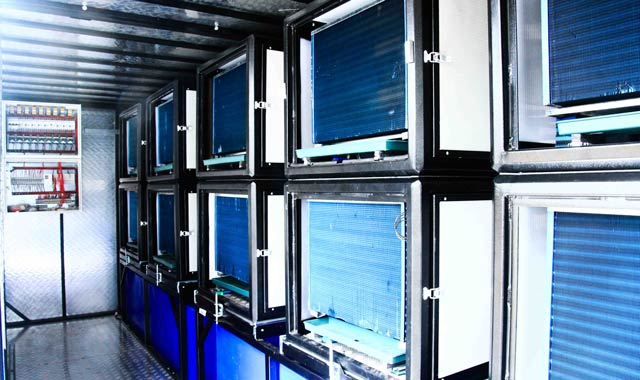

The firm’s products, which are modular in nature and fully manufactured in South Africa, are able to produce as much as a thousand litres of water a day, simply by tapping into the water vapour in the earth’s atmosphere. And the water the machines produce is clean and completely safe to drink.

There are two main ways that one can get liquid water from the atmosphere. The first uses desiccant technology, where a material absorbs moisture from the air. The second, which Cirrus employs, uses cooling condensation technology, which, Jones says, uses less energy.

AWG solutions are particularly useful in areas where it’s difficult or impossible to pipe in drinking water, such as at remote mining operations, although Jones is also hoping to drum up interest from the corporate market, where the technology could replace bottled water.

Jones explains that even in fairly dry environments, such as on the South Africa’s Highveld in the winter months, the air is still sufficiently humid to extract water. A fan sucks air into a machine, which then passes over cold coils — tubes that are cooled to just below the dew point, the temperature at which water vapour condenses into liquid — creating potable water.

“The machinery, through programmable logic controllers, has sensors that measure humidity and temperature, then … is able to determine how cold the coils should be and adjusts those temperatures so it drops below dew point so we can maximise water output,” Jones explains.

“Air blows over the cold coils and water condenses and drips into a storage tank. It’s then put it through an activated carbon filter, which improves the taste and captures any particulates that might be in the water.”

Owners of the machine can access it through a Web-based dashboard to see information such as the stock levels of water, the production rate, how much is being used, the temperatures of the coils, the power consumption and the climatic conditions.

“The reason that’s important is most of these guys are replacing bottled water with atmospheric water,” Jones says.

He says AWG solutions require less logistical administration than bottled water.

Other than office environments, Cirrus Water targets companies like mines that have remote locations where there is no access to municipal water infrastructure and where bottled water would otherwise have to be trucked in or sourced via boreholes.

The company also targets the top end of the home market. “We are seeing interest on the KwaZulu-Natal north coast, where there’s a drought with water restrictions in place. Some of the wealthier residents are looking at our systems.”

Depending on volumes consumed, Jones says AWG technology works out significantly cheaper than buying bottled water. The atmosphere is also a more sustainable source of water, Jones says.

“Bottled water is R3 to R20/litre. Our water costs at most about R2,20/litre during amortisation of the capital expense. Once amortised, you’ll be paying around 70c/litre.”

Energy consumption is not insignificant, however. A 100-litre/day unit consumes about 1,5kW of electricity, or a little less than a domestic kettle. But when connected to solar power, water can be produced cleanly. Bottled water is much more harmful to the environment as it has to be transported, and empty plastic bottles disposed off, Jones says.

The water produced by Cirrus’s AWG technology is slightly alkaline, he says. Filters remove particulates, and hydrogen sulfide — the gas that causes acid rain — in South Africa’s atmosphere is so low it doesn’t have an impact on water quality.

For peak production, relative humidity must be above 40%. In arid areas, it will often fall below that level during the day, but at night, when the temperature is lower, humidity rises, even in deserts. To resolve the low humidity dilemma, Cirrus Water is working on a new technology, still in “beta”, where a machine can use a source of grey water to beef up the humidity.

“We use the latent heat of the machinery to get water to a vapour state, so it pushes up the humidity to the threshold level so that the machines can run an optimum level,” Jones explains. “We would get typical production of five litres of clean water with one litre of grey water pushing up the humidity.”

Those interested in buying the technology, especially individuals, will have to have deep pockets. Hundred litre modules cost up to R150 000, which includes a dispenser, piping and storage and a couple of pumps. The minimum cost for a home is about R130 000. But there’s an option to split the water supply between houses in an estate, for example, with flow meters at each home to monitor consumption. — © 2015 NewsCentral Media