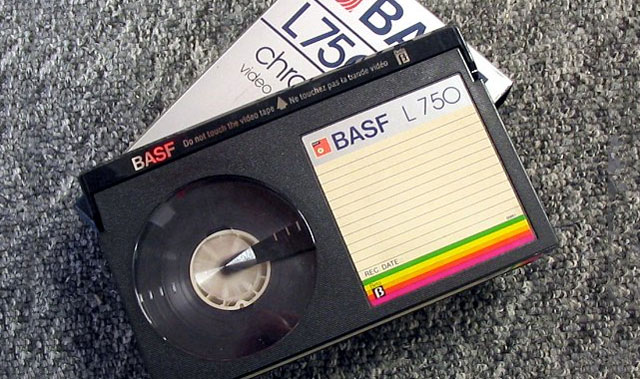

Sony announced this week that it will stop selling Betamax cassettes from March 2016. It was a format that appeared not to succeed as Sony had desired.

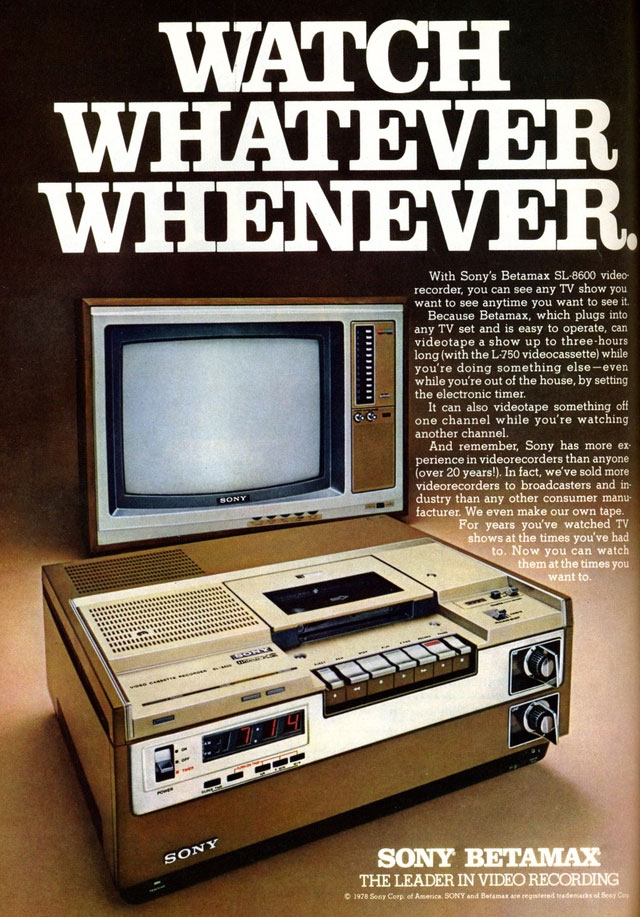

Betamax was introduced by Sony on 16 April 1975 with the SL-6300 video cassette recorder (VCR) deck and the LV-1801, a television/VCR combination unit that incorporated the SL-6300 and an 18-inch Trinitron colour television.

The name Betamax came from combining “beta”, a Japanese word which described the recording process, with “max”, which came from the tape path when viewed from above closely resembling the Greek letter of beta.

Developing the technology was only the first battle. Sony had to also convince the consumers that this new technology should be introduced into their homes.

For Sony, the uptake of television was on its side. At the time of introducing the new Betamax VCR desk, more than 90% of Japanese households had a colour television. With the release of Betamax television, time-shift viewing, a term commonly used in association with television viewing today, commenced and allowed the public to “watch, whatever, whenever” on their television.

The concept of time-shifting and recording content created tension between Sony and content creators. Universal Studios and Walt Disney were two of the film industry corporations that attempted to bring an end to video recording technology, in a US court case battle.

The district court found:

Even if it were deemed that home-use recording of copyrighted material constituted infringement, the Betamax could still legally be used to record non-copyrighted material or material whose owners consented to the copying. An injunction would deprive the public of the ability to use the Betamax for this non-infringing off-the-air recording.

Despite appeals, the supreme court agreed and the Betamax ruling still has implications today for the manufacturers of technology designed for legitimate use, but which can also be used to infringe copyright.

The debate of the VCR’s impact on various media industries continued into the 1980s. But Betamax didn’t just have to battle public uptake and the legalities, it also battled a competing format.

VHS killed the Betamax

A year after the release of Betamax, the rival Japanese tech manufacturer JVC released its own VCR format called Video Home System, better known as VHS.

Sony argued that JVC’s VHS incorporated the Betamax format. This was due to Sony freely disclosing information about Betamax to JVC, in a hope to unify their product specifications. Another Japanese tech manufacturer Matsushita was also approached.

Despite their similarities, the two formats differed in size and were incompatible. This created a battle between the two formats around the home VCR market.

The success of VHS over the rival Betamax was evident in the US. In its first year of sales, VHS took 40% of Sony’s business. By 1987, 90% of the US$5,2bn VCR market sales were VHS. Furthermore, by 1988, 170m VCR’s had been sold worldwide, of which only 20m (12%) were Betamax.

Sony admitted defeat and by 1988 commenced selling the VHS format in conjunction with its Betamax format.

There are many arguments put forward as to why VHS won the battle. Was it due to the fact that VHS could record two hours, double that of Betamax? Was it the marketing of VHS, or simply due to “the whole product” doing want consumers wanting for the right price?

The media format wars had not finished by any means. Now the format battle was associated with disc media. Recently there has been the battle of high-definition DVDs: Sony’s Blu-ray versus Toshiba’s HD-DVD. This time Sony won.

Sony has also recently announced the arrival of its Ultra HD Blu-ray opening the battle grounds of the ultra-high-definition (4K) disc market.

But in a digital world, consumers are watching their video content via the Internet, across multiple screens with no physical media, tape, disc or otherwise.

So do all of these formats matter anymore? Will disc media die? Will varying formats become less of an issue in a digital world?

Digital video compression was first associated with H.120 in 1984 and since then there have been several improvements in image quality. This is without looking at the variation in file extensions.

Format wars will not go away anytime soon. Unlike the battle of physical media, where a consumer would purchase one device which was associated with one format, digital allows one device that can access multiple formats.

While some may argue this to be a positive, this choice in digital formats may create more frustration for consumers. To watch content, they may be required to change the software, upgrade the software or download specific software associated with that video format.

From a professional perspective, no longer can producers of video content think about a singular platform, but must make sure that the content is available across a number of platforms, in a number of formats, which all have individual specifications.

These various changes in media formats have all occurred in the 40 years since Sony’s Betamax was released. Where will the format wars be in 40 years’ time?![]()

- Marc C-Scott is lecturer in screen media at Victoria University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation