From the legendary Tower of Babel to the iconic Burj Khalifa, humans have always aspired to build to ever greater heights. Over the centuries, we have constructed towering edifices to celebrate our culture, promote our cities — or simply to show off.

Historically, tall structures were the preserve of great rulers, religions and empires. For instance, the Great Pyramid of Giza — built to house the tomb of Pharaoh Khufu — once towered over 145m high. It was the tallest man-made structure for nearly 4 000 years, before being overtaken by the 160m tall Lincoln Cathedral in the 14th century. Other edifices, such as Tibet’s Potala Palace (the traditional home of the Dalai Lama), or the monasteries of Athos were constructed atop mountains or rocky outcrops, to bring them even closer to the heavens.

Yet these grand historical efforts are dwarfed by the skyscrapers of the 20th and 21st centuries. London’s Shard looms at 310m tall at its fractured tip — but it’s made to look small by the world’s tallest building, Burj Khalifa, which stands at more than 828m. And both these behemoths will be left in the shadows by the Kingdom Tower in Jeddah. Originally planned by architect Adrian Smith to reach 1 600m, the tower is now likely to reach 1km high once it’s completed in 2020.

So, how did we make this great leap upwards?

We can trace our answer back to the 1880s, when the first generation of skyscrapers appeared in Chicago and New York. The booming insurance businesses of the mid-19th century were among the first enterprises to exploit the technological advancements, which made tall buildings possible.

Constructed in the aftermath of the great fire of 1871, Chicago’s Home Insurance building — completed in 1884 by William Le Baron Jenney — is widely considered to be the first tall building of the industrial era, at 12 stories high.

Architects Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler first coined the term “tall office building” in 1896, drawing on the architectural precedent of Italy’s Renaissance palazzi. His definition denoted that the first two stories are given over to the entrance way and retail activity, with a service basement below, repeated storeys above and a cornice or attic storey to finish the building at the top. Vertical ducts unite the building with power, heat and circulation. This specification still holds good today.

The American technological revolution of 1880 to 1890 saw a burst of creativity that produced a wave of new inventions that helped architects to build higher than ever before: Bessemer steel, formed into I-sections in the new rolling mills enabled taller and more flexible frame design than the cast iron of the previous era; the newly-patented sprinkler head allowed buildings to escape the strict, 23m height limit, which was imposed to control the risk of fire; and the patenting of AC electricity allowed elevators to be electrically powered and rise to ten or more stories.

Early tall buildings contained offices. The typewriter, telephone and US universal postal system also appeared in this decade, and they revolutionised office work and enabled administration to be concentrated in individual high-rise buildings within a city’s business district.

Changes in urban life also encouraged the switch to taller, higher-density facilities. Street trams, subways and elevated rail links provided the means to deliver hundreds of workers to a single urban location, decades before the European motor car appeared on American streets and reshaped urban form away from the city grid.

Apart from a few high-rise mansion blocks around Central Park, New York, the terraced house reigned supreme in the crowded cities of the pre-motor car age, such as Paris, London and Manhattan, and evolved to nine stories in ultra-dense Hong Kong.

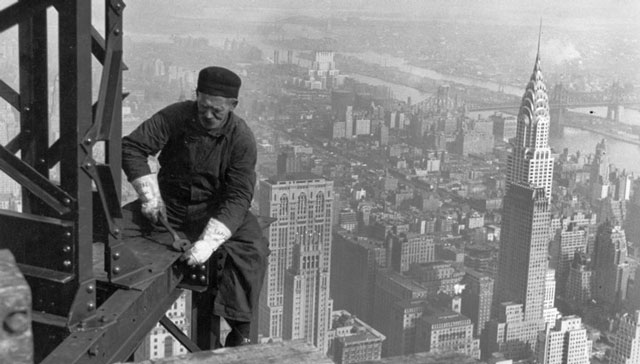

Early office towers filled their city blocks entirely, with buildings enclosing a large light and air-well, as a squared U, O or H shape. This permitted natural light and ventilation within the building, but didn’t provide any public spaces. Chicago imposed a height limit of 40m in 1893, but New York raced ahead with large and tall blocks. Many of these, such as the Singer, Woolworth, MetLife and Chrysler buildings, tapered off with “campanile” towers, battling to be tallest in the world.

Second-generation giants

In 1915, following the completion of the 40-storey Equitable building on Broadway, there was such alarm at the darkening streets that New York introduced “zoning laws” that forced new buildings to step ziggurat-like as they rose, in order to bring daylight down to street level.

This meant that while the base still filled the city block, the rest of the tower would rise centrally, stepping back every few stories, and it forced the service core to the building’s centre, leading to the loss of the light-well and making mechanical ventilation and artificial lighting essential for human habitation. This was a radical change in the shape of tall buildings, and the second generation of skyscrapers.

As architectural historian Carol Willis would have it, “form follows finance”: the developers of early 20th century high-rise office blocks would work out how to maximise the amount of usable floor space in a city site, before asking an architect to put a wall around it. Such vast wall surfaces with conventional windows invited patterns of geometric decoration, and the ziggurat style came to be the most recognisable architectural symbol of the Art Deco movement.

The mania for profit-driven tall development got out of hand in the late 1920s, however, and culminated in 1931 with the Chrysler and the Empire State buildings. The oversupply of office buildings, the depression of the 1930s and World War 2 brought an end to the Art Deco boom. There were no more skyscrapers until the 1950s, when the post-war era summoned forth a third generation: the International Style, the buildings of darkened glass and steel-framed boxes, with air conditioning and plaza fronts that we see in so many of the world’s cities today.![]()

- David Nicholson-Cole is assistant professor in architecture, University of Nottingham

- This article was originally published on The Conversation