In 1977, five years before ET asked to “phone home”, two robotic spacecraft began their own journey into space.

Almost 46 years later, after exploring the solar system and beyond, one of those spacecraft – Voyager 2 – has lost contact with Earth.

All communication with Voyager 2 goes through Nasa’s Deep Space Station 43, a 70m radio dish at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex operated by CSIRO.

Contact was lost more than a week ago. After intense efforts at Nasa and in Canberra, we have detected a faint “heartbeat” signal from the craft – and we’re confident of re-establishing full contact.

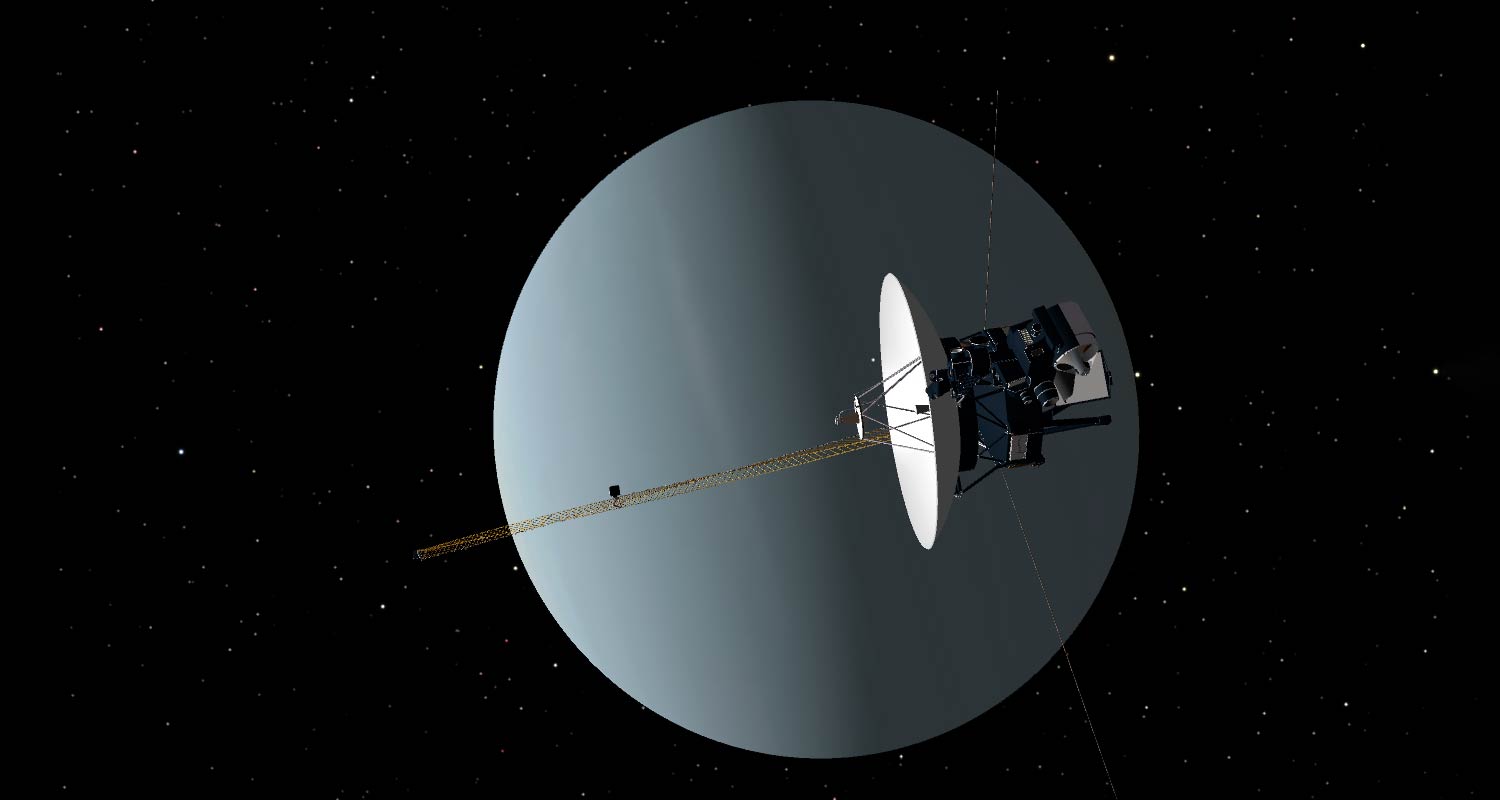

Nasa’s twin Voyager spacecraft – Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 – were designed to complete a “grand tour” of the solar system, visiting the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Throughout the billions of kilometres of their journeys, the Voyagers stayed in touch with Earth through the three antennas of the Deep Space Network. One is in Madrid, Spain; a second in Goldstone, California; and the third in Canberra, Australia.

Having completed their tasks in 1989, both Voyager 1 and 2 have long since left our solar system behind. They are now exploring interstellar space – the space between the stars.

20 billion kilometres

Voyager 1 is currently 24 billion kilometres from home, with Voyager 2 not far behind at 20 billion kilometres.

On 21 July, a series of planned commands sent to Voyager 2 inadvertently caused the spacecraft’s antenna to point two degrees away from Earth. As a result, the spacecraft is unable to receive commands or transmit any data back to Earth.

Mishaps like this are not uncommon in space exploration. The Nasa team is expert at problem solving, and has a good track record of keeping spacecraft flying long after their prime mission has ended.

Nasa’s science and engineering teams have dealt with communication drop-outs before, with both Voyagers. Their efforts have already quadrupled the planned 12-year life of the craft, so they don’t think we’ve heard the last from Voyager 2.

It’s an enormous achievement that we still have contact with these spacecraft at all, given their enormous distance from Earth and the relative weakness of the signal received through the big antenna dishes in Canberra. Even when Voyager 2 is pointing at Earth, its signal is already a whisper from space, billions of times weaker than the power generated by a tiny watch battery.

The last time Voyager 2 was out of contact was in March 2020, when the dish at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex was shut down for a scheduled 11-month upgrade project. Ahead of the shutdown, commands were sent to Voyager 2 to program the spacecraft to maintain operations without needing to hear from Earth for an extended period.

Canberra’s Deep Space Station 43 is the only antenna in the world that can communicate directly with both Voyagers. Its sister stations in the northern hemisphere are unable to “see” Voyager 2, because Earth is in the way.

Since Voyager 2’s antenna was tweaked off target, we have been using Deep Space Station 43 to listen intently for any signal. Eventually this effort paid off, with the detection of the craft’s carrier tone – a “heartbeat” indicating Voyager 2 is still transmitting.

Now attempts will be made to relay commands to Voyager 2 and tell it to reorientate its antenna towards Earth.

If those attempts fail, Voyager 2 is already programmed to use the sun and the bright star Canopus to reorientate itself several times each year. The next scheduled reset will occur on 15 October, which should automatically enable communications to resume.

Voyager 2, into interstellar space

The Canberra team feels a very close connection to this distant traveller. We have been with it on every step of its journey so far, and plan to continue to provide mission support for however long the mission lasts.

Voyager 2 was launched on 20 August 1977 and reached Jupiter in July 1979, a few months after Voyager 1. It proceeded to Saturn for a flyby of the ringed planet in 1981, and then had encounters with Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in August 1989, ending the so-called “grand tour”.

As both spacecraft were in good health, they were given an extended mission to reach the edge of our solar system, where the influence of the sun’s energy ends. The Voyagers are now in the “clear air” of interstellar space and can, for the first time, make direct measurements of this environment.

The data they have returned is changing our understanding of the universe. The teams at Nasa and here in Canberra are confident there is more science and discoveries to come, when Voyager 2 once again phones home.![]()

- The author, Glen Nagle, is outreach manager, Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, CSIRO

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence