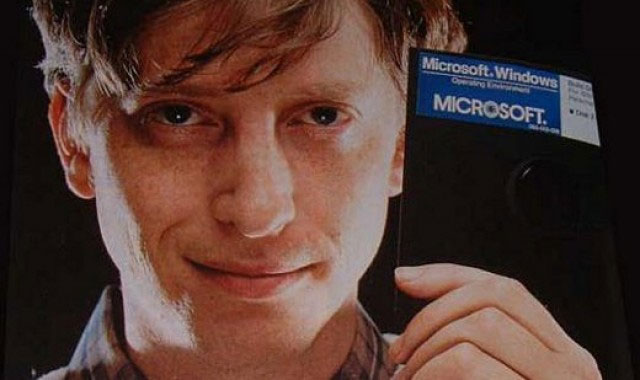

29 July 2015 is an important date for Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s CEO. Twenty years after Bill Gates introduced Windows 95 to the world, he is launching another version of the ubiquitous software that promises an equally seismic shift.

This is not just another update to the PC operating system. It marks the manifestation of Nadella’s bold vision for Microsoft to look into the future and deliver next-generation experiences for individuals and enterprises.

It’s a huge challenge, and it is still uncertain if he’ll succeed. He has to seamlessly weave together devices, software applications and cloud services from both Microsoft and its partners to build a vibrant ecosystem that’s capable of vying against the ones orchestrated by Apple and Google.

Sceptics wonder if Windows 10, offered as a free upgrade, can help it regain its position at the top. Investors worry if his ideas of shifting the business model from charging for software to earning fees for services on the cloud will make it go the way of IBM’s similar, painful transition. Others wonder if he can win with a vision of “mobile-first, cloud-first” without a credible mobile operating system or sizeable share of the online storage market?

This is a critical moment for Nadella. Microsoft has stumbled repeatedly in recent years as it’s struggled to compete with Apple and Google in the worlds of smartphones, search and wearables. While Windows still dominates desktops with a 91% share, its presence in the fast-growing mobile market remains stuck in the single digits (just 2%).

Coming 19 years and 11 months since the launch of Windows 95 — an operating system that revolutionised the industry at the time — Windows 10 provides a fresh opportunity to do it again.

I’ve been studying the strategies of companies in the digital sector for the past two decades. My research suggests there are six things Nadella will need to do to win — and he’ll need to do them well and with conviction, confidence and speed.

First, it’s important to redefine the scope of Microsoft’s platform. Most look at Windows 10 as PC-centric, when in reality it is broader than that.

The future is not about computers, laptops and mobile phones being treated separately. It is about a digitally connected world with about 50bn devices linked to the so-called Internet of things. The platform for the Internet of things is still evolving, and Microsoft is in a good position to become the essential building block it in a way that defines how we live, work and play.

He can do this by inviting the software development community to treat Windows 10 Universal Applications Platform as their primary gateway to build apps that scale across devices of varying shapes and sizes.

The next step is clarifying the role of first-party hardware in Microsoft’s strategy. As it pursues this plan to become the key gateway to the Internet of things, managing the inevitable tensions between the devices it continues to create and those of its partners will be tricky.

Nadella will need to convince hardware partners that its continuing efforts in that direction, such as the Surface 3 tablet or the much larger Surface Hub collaboration screen, are meant only to showcase its vision and not as serious competition to the breadth of devices possible for Windows 10.

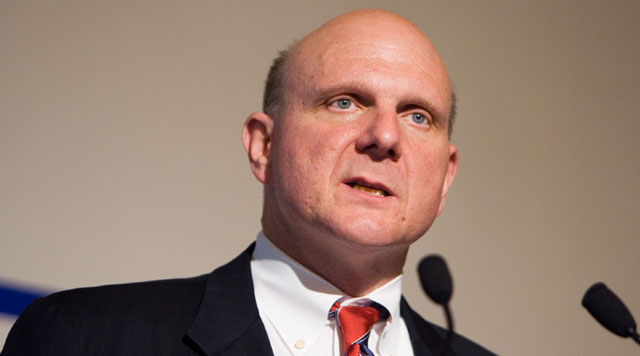

Third, in the same vein, a willingness to interoperate with competitors will be important. Unlike previous CEO Steve Ballmer, Nadella has so far shown more openness to work with companies that could be considered Microsoft’s rivals.

Two key elements of that strategy include:

- Demonstrating that the announced relationships with Adobe, Salesforce and Box are more than symbolic gestures.

- Gaining credibility with the chief information officers at major enterprise customers by showing how their IT roadmap could be predicated on seamlessly integrating Microsoft and non-Microsoft offerings.

Stores need a rethink

A fourth element involves reimagining Microsoft’s stores. Like Apple’s, they need to become experience destinations where customers can get a sense of Microsoft’s vision of how devices, software and cloud will come together.

But that’s where the comparison with Apple’s stores ends. Microsoft’s, by contrast, should be organised to demonstrate how consumers can connect their devices with partners’ applications and access content and services in the cloud.

Other ways the stores could be used include educating individuals so they can better protect against identity theft and fraud and explaining what happens with data from wearable devices like Microsoft Band and others. Helping people understand how their information is used in different situations will build trust with consumers by helping them make informed choices.

Fifth, Nadella needs to energise his engineering team to help him deliver on the connected experience underlying his plans.

He has inherited an organisation notorious for infighting, particularly under his predecessor. For his strategy to work, he has to get the engineering team to cooperate across the three parts of his strategy — software (Windows), apps (Office) and the cloud (Azure).

Nadella has designed his new organisational structure and designated his leadership team. But, he has to keep a watchful eye on how the teams work to overcome the dysfunctional culture that existed during Ballmer’s “lost decade”. This means that it’s important that innovations such as the HoloLens holographic computer and the Cortona voice-activated assistant not become standalone businesses — as happened with the Xbox — but are integrated with Windows 10 and the promised connected experience.

Lastly, Microsoft’s biggest challenge lies in its ability to effectively capture value in its new ecosystem.

Apple’s cash register is in its devices, from which it takes a 30% cut of every app, album or newspaper subscription purchased through its stores. Google’s cash register is in advertising. Can Microsoft successfully shift its cash registers from retailers, where it simply collects revenue from hardware and software sales, to the cloud, where it can more fully monetise the value of its services over a customer’s lifetime?

Chris Capossela, Microsoft’s chief marketing officer, recently laid out the four stages of monetisation for individuals: acquire, engage, enlist and monetise.

“Acquire” is getting individuals to use free apps such as Office for iPad or OneNote for Android. In the “engage” stage, individuals get committed and locked in to such apps, while in the “enlist” stage, they invite other users to create what are known as positive network effects. The final proof is in the monetisation stage: what’s the revenue per user and how can it be protected and expanded?

Similarly, for enterprises, the cash register shifts from multiyear licence fees based on the number of users to include security, services and enterprise app stores. Simply put: cash registers in this ecosystem are complex to design and control.

Microsoft’s ability to consistently show growth in revenues and profits at scale by leveraging the Windows ecosystems for individuals and enterprises is Nadella’s biggest test.

Finding a new formula

Nadella recognised early on that for too long Microsoft had operated with the outmoded formula that the PC was at the hub.

Early last year, he remarked in an interview with the New York Times about the need to go beyond the old formula:

Now, it is about discovering the new formula. So … how do we take the intellectual capital of 130 000 people and innovate where none of the category definitions of the past will matter? Any organisational structure you have today is irrelevant because no competition or innovation is going to respect those boundaries.

Recognition of the challenges ahead is an important hallmark of a good leader. Beyond 29 July, he will be tested for his ability to respond to the challenge by pulling his internal organisation and external partners in alignment to put Microsoft as a distinguished leader in the “mobile-first, cloud-first” world.

Bill Gates innovated by making the Windows software and Office applications central to the first wave of productivity at work and home. Ballmer failed to adapt to the shift to mobile. Now Nadella hopes to regain Microsoft’s relevance in an increasingly digital world.

We are still in its early stages. Nadella’s success will depend on his ability to pull together the energy of 130 000 Microsoft employees but also several hundred thousand software developers to believe in the future of Windows beyond the PC.![]()

- N Venkat Venkatraman is professor of digital strategy at Boston University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation