Microsoft’s aim to make Windows 10 run on anything is key to its strategy of reasserting its dominance. Seemingly unassailable in the 1990s, Microsoft’s position has in many markets been eaten away by the explosive growth of phones and tablets, devices in which the firm has made little impact.

To run Windows 10 on everything, Microsoft is opening up.

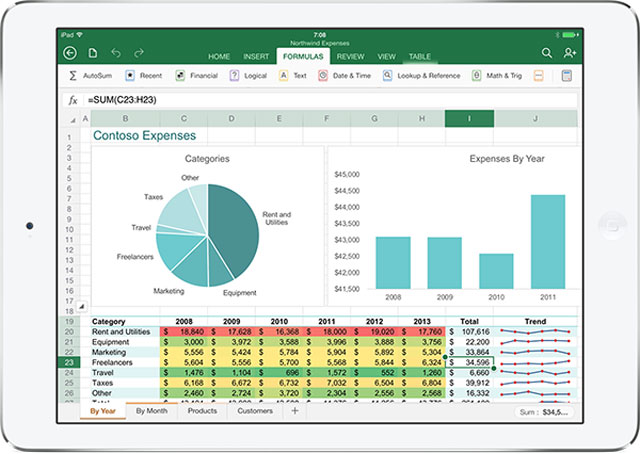

Rather than requiring Office users to run Windows, now Office 365 is available for Android and Apple iOS mobile devices. A version of Visual Studio, Microsoft’s key application for programmers writing Windows software, now runs on Mac OS or Linux operating systems.

Likewise, with tools released by Microsoft, developers can tweak their Android and iOS apps so that they run on Windows. The aim is to allow developers to create, with ease, the holy grail of a universal app that runs on anything. For a firm that has been unflinching in taking every opportunity to lock users into its platform, just as with Apple and many other tech firms, this is a major change of tack.

So, why is Microsoft trying to become a general purpose, broadly compatible platform? Windows’ share of the operating system market has fallen steadily from 90% to 70% to 40%, depending on which survey you believe. This reflects customers moving to mobile, where the Windows Phone holds a mere 3% market share. In comparison Microsoft’s cloud infrastructure platform Azure, Office 365 and its Xbox games console have all experienced rising fortunes.

Lumbered with a heritage of Windows PCs in a falling market, Microsoft’s strategy is to move its services — and so its users — inexorably toward the cloud. This divides into two necessary steps.

First, for software developed for Microsoft products to run on all of them — write once, run on everything. As it is there are several different Microsoft platforms (Win32, WinRT, WinCE, Windows Phone) with various incompatibilities. This makes sense, for a uniform user experience and also to maximise revenue potential from reaching as many possible devices.

Second, to implement a universal approach so that code runs on other operating systems other than Windows. This has historically been fraught, with differences in approach to communicating, with hardware and processor architecture making it difficult. In recent years, however, improving virtualisation has made it much easier to run code across platforms.

It will be interesting to see whether competitors such as Google and Apple will follow suit, or further enshrine their products into tightly coupled, closed ecosystems. Platform exclusivity is no longer the way to attract and hold customers; instead the appeal is the applications and services that run on them. For Microsoft, it lies in subscriptions to Office 365 and Xbox Gold, in-app and in-game purchases, downloadable video, books and other revenue streams — so it makes sense for Microsoft to ensure these largely cloud-based services are accessible from operating systems other than just their own.

Platform vs services

Is there any longer any value in buying into a single service provider? Consider smartphones from Samsung, Google, Apple and Microsoft: prices may differ, but the functionality is much the same.

The element of difference is the value of wearables and “Internet of things” devices (for example, Apple Watch), the devices they connect with (for example, an iPhone), the size of their user communities, and the network effect.

From watches to fitness bands to Internet fridges, the benefits lie in how devices are interconnected and work together. This is a truly radical concept that demonstrates digital technology is driving a new economic model, with value associated with “in the moment” services when walking about, in the car, or at work. It’s this direction that Microsoft is aiming for with Windows 10, focusing on the next big thing that will drive the digital economy.

Tech firms will try to grow ecosystems of sensors and services running on mobile devices, either tied to a specific platform or by driving traffic directly to their cloud infrastructure.

Apple has already moved into the mobile health app market and connected home market. Google is moving in alongside manufacturers such as Intel, ARM and others. An interesting illustration of this effect is the growth of digital payments — with Apple, Facebook and others seeking ways to create revenue from the traffic passing through their ecosystems.

However, the problem is that no single supplier like Google, Apple, Microsoft or Internet services such as Facebook or Amazon can hope to cover all the requirements of the Internet of things, which is predicted to scale to over 50bn devices worth US$7 trillion in five years. As we become more enmeshed with our devices, wearables and sensors, demand will rise for services driven by the personal data they create. Through “Windows 10 on everything”, Microsoft hopes to leverage not just the users of its own ecosystem, but those of its competitors, too.![]()

- Mark Skilton is professor of practice at the University of Warwick

- This article was originally published on The Conversation