Three years ago, the African Development Bank launched an initiative to speed up the supply of electricity in Africa. Launching the New Deal on Energy for Africa, the bank’s president, Akinwumi Adesina, remarked: “Africa is tired of being in the dark.”

Three years ago, the African Development Bank launched an initiative to speed up the supply of electricity in Africa. Launching the New Deal on Energy for Africa, the bank’s president, Akinwumi Adesina, remarked: “Africa is tired of being in the dark.”

Other high-profile initiatives — including Power Africa and Sustainable Energy for All — have also prioritised electricity for Africans.

But on-the-ground observation and interviews throughout Africa suggest that the United Nations’ development goal of providing “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” remains a distant dream for many.

Survey teams from the African research network Afrobarometer, asked people in 34 countries on the continent about access to electricity, and recorded the presence of an accessible grid. They found that expansion of national electric grids appeared to have largely stalled in recent years. And even in areas where an electric grid was accessible, service often remained unreliable.

About four in 10 Africans (42%) lack an electricity connection in their homes. This is either because they are in zones not served by an electric grid or because they are not connected to an existing grid. In 16 countries, more than half of respondents had no electricity connection. This included more than three quarters of citizens in Burkina Faso (81%), Uganda (80%), Liberia (78%) and Madagascar (76%).

Unreliable

Nor does being connected guarantee power. Power cuts continued to plague some countries. About one in seven respondents (14%) had a connection but reported that their power worked half the time, or less. All in all, taking into account households with no access to a grid, no connection to an existing grid or an unreliable supply, only 43% of Africans enjoyed a reliable supply of electricity. While the comparable figure was nine out of 10 in Mauritius (98%) and Morocco (91%), it barely exceeded one in 20 citizens in Malawi (5%) and Guinea (7%).

Between late 2016 and late 2018, Afrobarometer teams conducted 45 823 face-to-face interviews in 34 countries. They also recorded the presence of basic infrastructure. They found that, on average, two-thirds (65%) of citizens lived in zones served by an electric grid. This was virtually the same number found in a survey done three years earlier.

Access to an electric grid varied widely by country. While virtually all Cabo Verdeans, Mauritians and Tunisians lived in zones served by a grid, fewer than one-third of citizens in Burkina Faso (28%), Madagascar (29%), Mali (30%), Guinea (32%) and Liberia (33%) enjoyed the same access (see figure 1).

The teams also found stark regional differences: about nine in 10 North and Central Africans resided in zones served by an electric grid (91% and 86%, respectively). But only around half (55%) of East Africans do.

As far as recording progress was concerned, East Africa was the only region in which Afrobarometer found significant advances. The electricity grid had been extended by seven percentage points since its 2011/2013 survey.

As usual, rural residents suffered the most glaring disadvantages. On average, they were less than half as likely (44%) as their urban counterparts (92%) to live in an area served by a grid.

Given the high cost of an electric connection, not all households within reach of an electric grid were connected. In areas with access to a grid, poor households were half as likely as well-off households to have a connection.

Ghanaians report a striking improvement in reliability: the share of citizens with regular power doubled between 2014 and 2017, from 37% to 79%, in large part as a result of increased supply by independent power producers (under contracts initiated under the previous administration) that reduced large-scale load shedding experienced in 2014 and 2015. Other countries recording double-digit percentage point improvements in reliable electricity supply are Zimbabwe (+18 points), Sierra Leone (+16), Botswana (+14), eSwatini (+13), Togo (+12) and Tanzania (+11).

The largest decline in reliable electricity supply between 2014/2015 and 2016/2018 occurred in South Africa (-21 points), which has experienced power cuts as the utility Eskom battles to maintain its generating plants and keep pace with growing demand, followed by Cameroon (-19) and Côte d’Ivoire (-12).

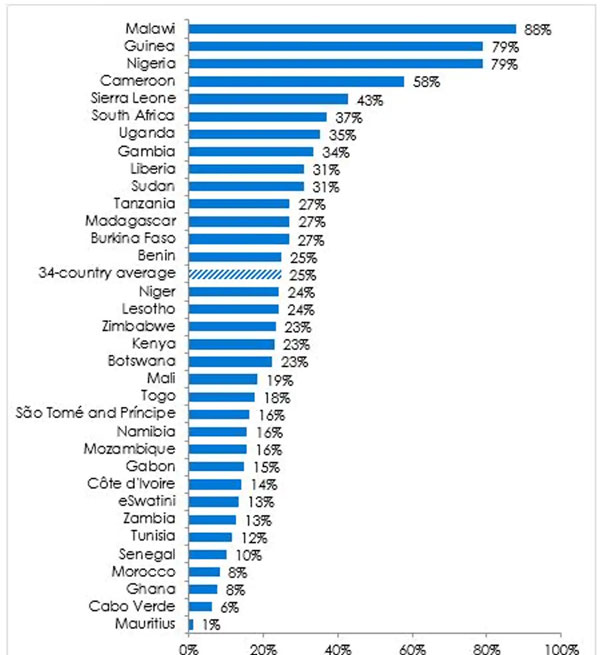

Looking only at households connected to the electric grid allows us to highlight the extent of poor-quality supply. Across 34 countries, one in four respondents (25%) who have an electricity connection say their electricity works “about half the time” or less (see image above). Quality is a particular problem in Malawi, where 88% of connected households do not have reliable electricity, and the situation is only slightly better in Guinea (79%) and Nigeria (79%).

Given that only 43% of Africans enjoy a reliable supply of electricity, it’s hardly surprising that fewer than half (45%) say their government is doing a good job on this issue. There are bright spots whose lessons can be learned, such as striking gains in reliable power supply in Ghana. But even countries that have managed to extend the electric grid over the past decade, such as Kenya, will need enormous efforts to increase supply, improve service, and expand the use of alternative energy sources if they hope to fulfil the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals.![]()

- Written by Carolyn Logan, deputy director of the Afrobarometer and associate professor in the department of political science and the African Studies Centre, Michigan State University

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence