Regular power interruptions started at least 10 years ago when problems at Eskom first surfaced. Since then, the situation has become worse every time a new crisis has hit the bungling state-owned electricity utility. No amount of damage to the economy or taxpayer outrage seemed to result in any visible and effective efforts to ensure reliable electricity at competitive rates.

Regular power interruptions started at least 10 years ago when problems at Eskom first surfaced. Since then, the situation has become worse every time a new crisis has hit the bungling state-owned electricity utility. No amount of damage to the economy or taxpayer outrage seemed to result in any visible and effective efforts to ensure reliable electricity at competitive rates.

A lot of people and businesses, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, have invested in generators and other alternatives to ensure electricity during load shedding. Most guest houses, filling stations, retailers, restaurants and whoever else seeks a competitive advantage during power cuts have installed some equipment to keep their businesses going during power failures.

These backup installations range from a small generator on the back porch or a battery-powered power supply and inverter to quite large installations comprising big backup generators that can power a business without interruption for hours, even if quite expensive to run.

Lately, a new trend has started to emerge. Not only are households and businesses investing in their own generating capacity to ensure electricity during power failures, they are increasingly aiming to become totally independent of Eskom.

Rapid advances in technology have pushed renewable energy sources from an expensive option that only environmentalists advocated to an economically viable alternative.

The International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) says in a recent study that the cost of renewable energy sources like wind and solar continue to fall drastically and will start to become cheaper than fossil fuels by 2020.

70% cost decline

Irena based its research on the cost of new and completed projects worldwide. While solar projects are still relatively expensive in comparison to hydro power, onshore wind and geothermal sources, the cost of solar plants has dropped by more than 70% since 2010 and continues to fall, says the report.

“Auction prices for photovoltaic projects have reached a record low per kilowatt-hour in Dubai, Mexico, Chile, Brazil, Canada and Germany. By 2020, all renewable power generation technologies that are now in use are expected to be comparable with fossil fuel, with most at the lower end of the range or undercutting fossil fuel.”

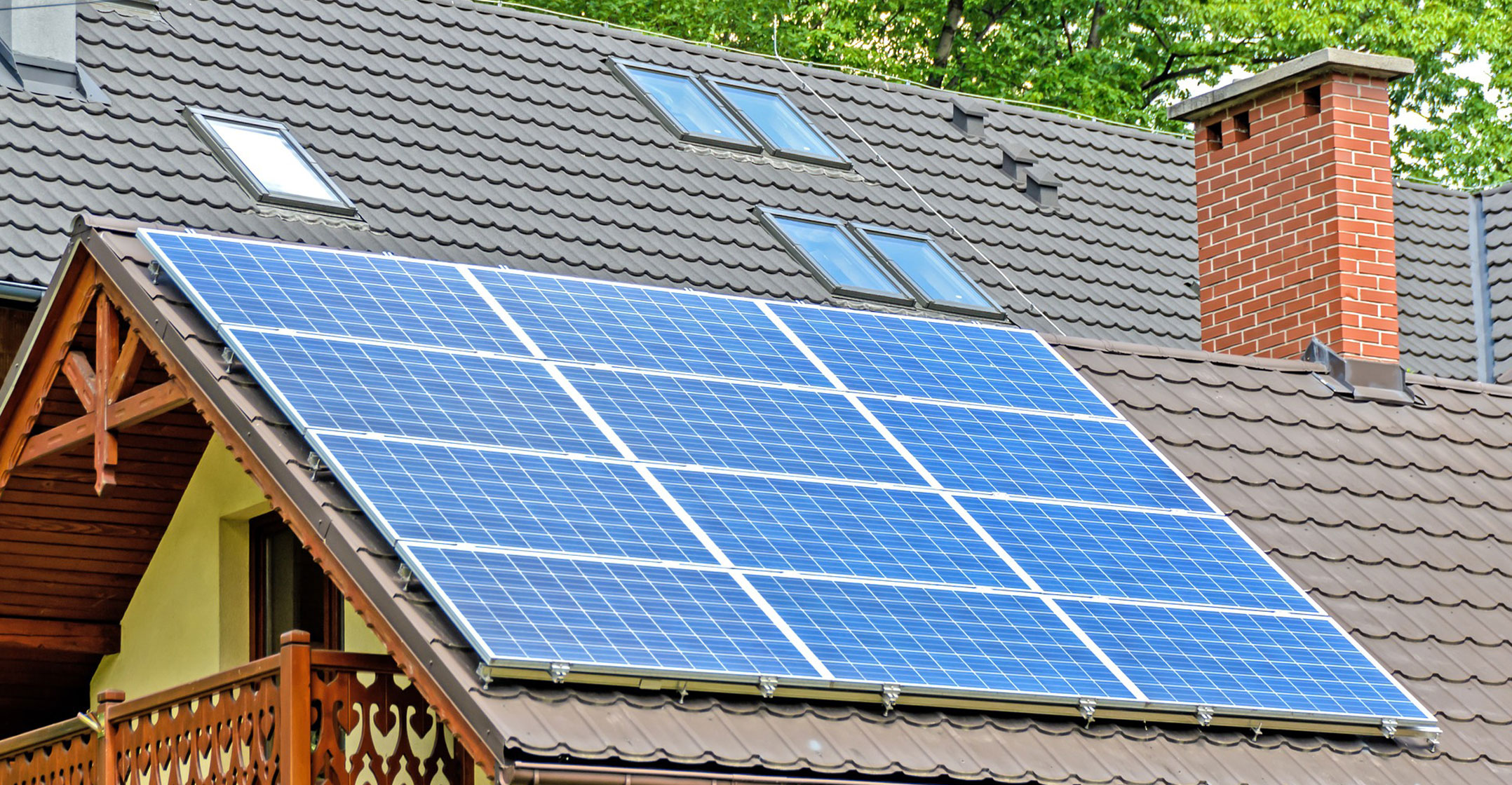

The lower prices of solar systems due to technological advances and more competition in the solar industry globally has resulted in a big drop in the capital cost to install a solar system for a small business or a household in South Africa, too. Meanwhile, Eskom’s slow decline motivated people to look for alternatives.

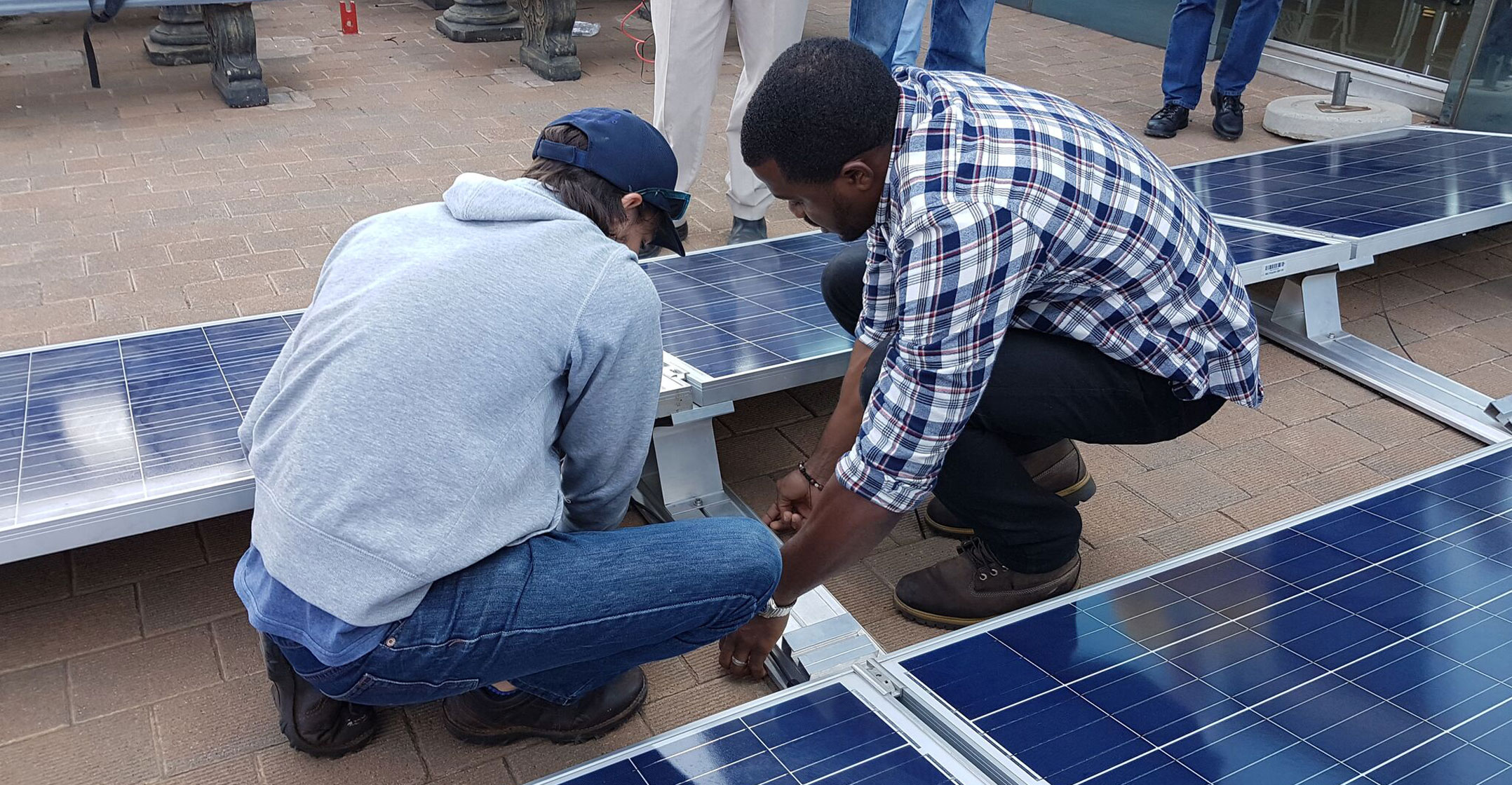

Peter Bergs, MD of Specialized Solar Systems, says demand for solar installations has increased significantly in the last few years. “More and more businesses are installing photovoltaic solar systems to reduce their energy cost. In addition, it gives them backup power during power failures.”

Peter Bergs, MD of Specialized Solar Systems, says demand for solar installations has increased significantly in the last few years. “More and more businesses are installing photovoltaic solar systems to reduce their energy cost. In addition, it gives them backup power during power failures.”

He says demand for residential installations has also increased sharply during the last two years as electricity prices have increased, while the cost of solar systems has fallen dramatically and the effectiveness of new generating technology has improved tremendously. “We are receiving a lot more enquiries lately because of the recent wave of load shedding,” he adds.

The cost of off-grid solar installations has decreased significantly over the last 10 years, with the prices of some components falling nearly 70%, according to Specialized Solar Systems’ website.

“The price of solar panels has decreased to around R5/W generating capacity compared to between R11 and R12/W 10 years ago,” says Bergs. This means that a 100W solar panel costs some R500 today compared to R1 200 in 2008.

Inverters — the heart of a solar system that converts 12V direct current to 220V alternating current to run household appliances — have also decreased in price, while their capacity, quality, effectiveness and features have improved significantly. For instance, most modern pure sine-wave inverters are cheaper than the older modified sine-wave inverters, and even cheaper than the bigger and bulkier square wave inverters of years ago.

Modern inverters combine charging controllers, battery management, seamless switchover from different power sources and computerised operation in one compact unit. Good quality inverters produce pure, stable electricity without dips and surges, which results in electrical and electronic appliances working better.

Completely off-grid

Bergs says it is notable that people are increasingly enquiring about off-grid systems that make businesses and households totally independent from the national energy grid rather than grid-tied systems.

Grid-tied systems are connected to the national electricity network, largely to reduce electricity costs. In short, grid-tied systems consist of solar panels (or a wind turbine) and an inverter, but do not include a battery bank. Energy from the solar panels is converted into electricity and used to power appliances, with the excess electricity feeding into the national grid.

Electricity from the grid is used when the house or business uses more electricity that its system generates, for instance, during the evening.

Off-grid systems include a battery bank to store electricity generated by the solar panels and are not connected to the local electricity network at all. Unfortunately, deep discharge solar batteries and more modern power walls are still very expensive, equal to about half the cost of a typical solar installation.

However, these off-grid systems offer total independence from the woes of the local municipality and Eskom’s troubles, and electricity failures are limited to times when it rains for a week without sunshine.

However, these off-grid systems offer total independence from the woes of the local municipality and Eskom’s troubles, and electricity failures are limited to times when it rains for a week without sunshine.

Bergs says the cost of off-grid systems has declined sharply in the last eight to 10 years. He estimates that the current cost to install an off-grid system to power a medium-sized house will be around R150 000 to R190 000, compared to more than R300 000 a decade ago.

Smaller generating systems — whether solar panels or big standby generators — are no longer a rarity and, if the trend continues, will add to Eskom’s challenges.

Ultimately, it is Eskom’s paying customers who are leaving the fold.

Last week, the City of Cape Town started a legal process to get permission to purchase electricity directly from the so-called independent power producers. Current legislation prescribes that private wind and solar farms can only sell their electricity to Eskom.

If the application succeeds, it will break Eskom’s monopoly and open the door to free-market competition and result in the development of more independent power producers. Other municipalities are investigating similar moves to reduce their dependence on Eskom.

George municipality has announced that it is looking at proposals for a biomass power station that will use wood chips from saw mills and other sections in the forestry industry to generate electricity.

GreenCape, an organisation that advances sustainable development, has joined forces with the City of Cape Town to encourage the installation of grid-tied rooftop solar systems to feed electricity into the local network. The idea behind the programme is that businesses and households can help to generate green electricity in a way that makes financial sense.

GreenCape says that at current installation costs and current electricity prices, the repayment of a solar system is as little as five years. “With solar panels that have a 25-year production warranty, it’s very much like buying 25 years’ worth of prepaid electricity by paying for five years’ electricity at current prices.”

There are also tax advantages for businesses as section 12B of the Income Tax Act provides for an accelerated depreciation allowance on the total cost of a solar system with a capacity of less than 1MW. “A maximum of 28% of the cost can be saved in the first year through a reduced tax bill,” says GreenCape.

How I went off-grid

I haven’t paid for electricity for nearly 10 years after installing a small solar system in 2009. At the time, since a transformer and a cable to my secluded cabin would have cost R60 000, a solar system made more sense.

My first 150W solar panel cost me R2 600 in 2009; the second, bought from the same supplier last year, was R1 400. I slowly added batteries to my battery bank and had to trade up to a better inverter because of lack of experience (and a much smaller variety to choose from) when I started off.

I quickly learnt that appliances use much more electricity than their specifications promise, and that components in the solar panels produce slightly less than their labels claim.

Admittedly, I do not use a lot of electricity. Besides, the first step in going the solar route is to reduce electricity consumption. I also learnt to adapt my consumption to whatever is available, especially on the second and third rainy day.

My small, R40 000 system powers what I need, but cannot handle a tumble dryer, multiple refrigerators and fridges, heaters and almost anything with a big heat element. A gas stove and gas geyser work better than their electric counterparts, and burning black wattle logs in a fireplace in winter is much better — and nicer — than the glow from an electric heater.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission