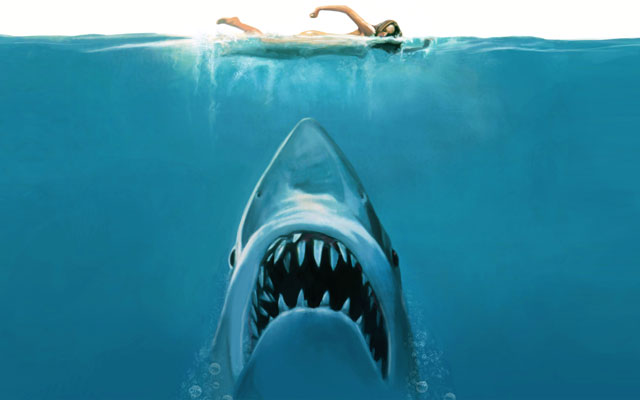

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is not particularly classy, but its 40th anniversary is a big deal for critics, fans and academics alike. In the US it has been marked with special screenings, while in the UK a dedicated academic conference at De Montfort University in Leicester was sold out, with a book to follow. But why is an improbable film about a shark still hitting the headlines 40 years on and what does that say about contemporary horror offerings?

Jaws has an almost legendary status in the history of Hollywood. By the mid-1970s, cinema had been edged out by the convenience of television, and was in danger of becoming an obsolete format. Some filmmakers thought the answer was to take cinema towards an adult audience, giving them something that could never be shown on TV. Soldier Blue (1970) raised the stakes when it came to explicit violence, Deep Throat (1972) for explicit sexual content, while Straw Dogs (1971) managed to do both.

In this climate, the horror genre was the ideal place for pushing boundaries. Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left was released in 1972, for example, but did not receive an uncut certificate in the UK until 2008. William Friedkin’s The Exorcist caused great controversy when it came out in 1973, while Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre appeared the following year.

Jaws did something else. It was a monster movie but it also became a must-see spectacle. It harked back to the glorious technicolour adventure films of earlier decades, but with a thoroughly modern style and approach. It was fast paced, tightly plotted and scripted, with a wide variety of characters for the audience to identify with.

It seemed to have too much edge to be a family film, including some nudity and of course violence. This gave it an aura of the forbidden, though in reality much more was implied than actually seen. In the UK and the US it received a PG certificate, meaning there was no fixed age restriction.

Marketing and distribution tactics aside, Jaws’s success at appealing to just about everyone is demonstrated even within the structure of the film itself. It is really three mini-films packed into one. The opening scene manages to cover what came to be the classic slasher movie, albeit predating the film normally credited with defining the genre, John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978).

Like many slasher films, the opening setting in Jaws is a place of transition, in this case a shoreline, where teenagers, are drinking, smoking and making out, with no adults in sight. A young woman separates herself from the crowd, hotly pursued by a libidinous, drunken young man. Two minutes later she has been terrorised and savaged by an unseen assailant before being dragged beneath the waves. It stands on its own as a short horror movie about lone teenagers in peril.

The second part is a community-under-threat story. Chief Brody, husband, father and chief of police, gradually comes to realise that his family and community are in trouble from a mysterious force in the water, exacerbated by the wilful blindness of politicians and narrow-minded commerce. This force is a proxy for any threat to the middle-American way of life that you care to mention — feminism, the Cold War or environmental catastrophe (indeed Jaws was followed by any number of “nature strikes back” films, such as Piranha (1978) and The Swarm (1978)). Famously, Jaws is not a film about a shark.

The final section of the film dispenses with the women and children and instead becomes an all-male action movie, with a plot rather too close to Moby Dick for some. Brody has been depicted as the family man, the shy boy afraid of the water and the seemingly ineffectual chief of police, who in his opening scenes was beset by islanders petitioning him to sort out various minor disagreements (which he seems to do little about). Played of course by Roy Scheider, he now comes of age by finding his inner steel. “Smile, you son of a bitch,” he growls to the shark just before blowing it up.

Jaws: the legacy

Jaws has a lot to answer for. It helped create the contemporary Hollywood machine, which demands huge mainstream audiences and high returns on investment. It thinks that you achieve this by ever-larger spectacle, aggressively hyped by saturation marketing. It was the beginning of cinema finding a blockbuster formula that could guarantee its future through the likes of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises and beyond.

For horror films, on the other hand, Jaws’ relatively mainstream appeal became a problem. In the new era of event cinema for everyone, an NC-17 certificate was something that advertisers and exhibitors didn’t want to be associated with. The received wisdom is that such films are not going to deliver those huge audiences and return on investments. (In theory the UK equivalent is an 18 certificate, but in practice it is regarded more like the UK’s R18, which is usually pornography.)

American horror films were forced to either rely on home video and low budgets if they wanted to push the boundaries, or to become blander and tamer to succeed in the cinema. Even torture-porn films, such as Saw (2004), have been cut to get the lesser R certificate in the States (meaning that a parent or guardian must be present, but no age restriction as such). Explicitness per se is no longer the answer.

The horror slate for 2015 and beyond does not suggest any major innovations are in the offing. It is dominated by remakes such as Poltergeist, which Variety dubbed “entertaining but fundamentally unnecessary”; and sequels such as Insidious 3, REC 4 or Paranormal Activity 5. It remains difficult to point to any silver linings amongst this fodder, though it is worth remembering that the most unsettling horror films have always come from outside Hollywood: from independent film makers, such as The Blair Witch Project (1999) which pioneered the “found footage” sub-genre; or from the vibrant Asian horror sector, which brought us The Ring (1998) and The Grudge (2002).

Unfriended, which has been creating the biggest horror stir in 2015, is really just a mashup of Blair Witch and The Ring. And with the change in Hollywood that came about after Jaws looking more permanent than ever, the next generation of unexpected, bespoke, peculiar and unnerving horror films is likely to come from the independents and overseas, too — particularly as distribution models continue to adapt to the sundry opportunities of the online world.![]()

- Catriona Miller is senior lecturer in media at Glasgow Caledonian University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation