The news that South Africa’s sovereign rating has been downgraded caught many by surprise. But it was long coming. The main reason for the rating agency’s decision is clearly concerns about political leadership in the country. Moody’s, which is expected to follow suit, has said as much, stating its decision to put the country on a negative outlook down to “the abrupt change in leadership of key government institutions”.

The downgrade by S&P comes on the back of a highly charged political environment in the ruling ANC. This culminated in the sacking of the finance minister Pravin Gordhan and his replacement with Malusi Gigaba. While the cabinet reshuffle is the proximate cause of the downgrade, South Africa’s political and institutional malaise goes deeper.

So, how does the country surf through these turbulent waters?

One hopes that the credit downgrade could help to focus the mind of the country’s political leadership to the task at hand, and that this will inject much-needed urgency for political change and economic reforms. The S&P assessment casts a ray of hope: “We could revise the outlook to stable if we see political risk reduced and economic growth or fiscal outcomes strengthen compared to our baseline projections.”

Piecemeal efforts towards change will not be enough. Bold leadership is required. But it’s inconceivable that the kind of action required can happen under President Jacob Zuma’s leadership.

The real chance to turn the country around is to do precisely what the Brazilians did last year — to impeach the president while building momentum in civil society to achieve political renewal as the basis for sustained economic recovery.

For nearly a decade now, international financial institutions and other international organisations have warned South Africa about a number of dangers. These include policy uncertainty, the consequences of low growth for social stability, and the need to attend urgently to industrial relations, especially in the mining sector.

Dire warnings are contained in a number of reports. These include the International Monetary Fund’s latest annual assessment of South Africa’s macroeconomic conditions, the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) periodic survey and the World Bank Economic Update.

South Africa experienced downgrades in 2012, 2013 and 2015. These should have been read as a harbinger of worse things to come. Government had ample time to draw appropriate lessons from these warnings, but chose to stick its head in the sand in the hope that problems would varnish. Meanwhile, the ruling party elevated factional battles above interest of the country.

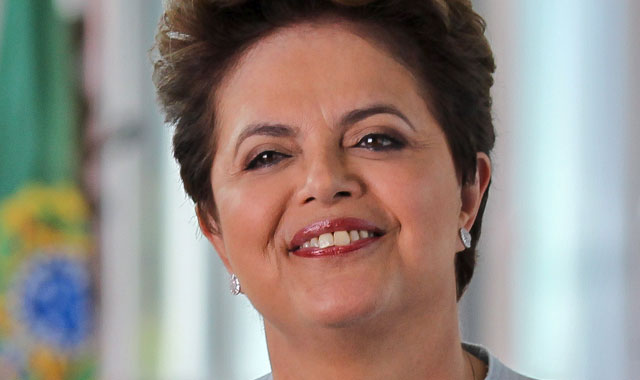

South Africa could have also drawn lessons from Brazil which was downgraded by S&P and Moody’s to sub-investment grade status in 2015 . This was in the wake of political unrest over a massive corruption scandal at the oil giant Petrobas, declining business confidence, growing policy uncertainty and President Dilma Rousseff’s weak leadership.

The downgrade further worsened Brazil’s growth outlook, with capital fleeing the country. Less than a year after the downgrade, the senate had thrown Rousseff out of office.

What next

In a sense, credit downgrades shouldn’t come as a surprise. They are like a medical report showing defects in the vital organs in the body while the patient is still alive and can do something about them, albeit requiring uncomfortable surgical procedure and a strong dose of medication.

In evaluating South Africa, S&P took into account the effectiveness of policymaking and stability of political institutions to respond effectively to socio-economic challenges, and found these wanting. The S&P statement specifically singled out the risk of cabinet reshuffle on fiscal and growth outcomes, the possibility of increase in the contingent liabilities of the state — in particular the likelihood of state-owned enterprises such as Eskom, the power utility, to draw down on government guarantees — and increased political risks in general in the current year.

The consequences of this downgrade are not difficult to discern: they will trigger a disposal by pension funds and other institutional investors of South African debt, since these funds are not allowed to hold sub-investment grade (or speculative) bonds. Sub-investment grade status will increase South Africa’s borrowing costs from global markets.

Interest rates are likely to go up, with debt-laden consumers bearing the brunt. Capital will flee in search of safer havens for healthy returns.

There are political implications, too. Government spending will be constrained, including for welfare programmes and delivery of various public services, raising prospects of waves of political unrest in the run up to 2019 elections. And there’s likely to be more pressure on the government to increase public servants’ salaries.

Further accentuating the strain on the economy is the fact that growth is likely to remain in the doldrums; with the employment outlook remaining bleak for the foreseeable future. Export growth is projected to remain flat during 2017 and 2020. As S&P notes, economic growth is unlikely to come from business investment, since business will be withholding capital in the face of heightened political risk.

Solutions

Bold political and economic reforms are urgently needed. Tough times such as the ones South Africa is headed towards can also be crucibles for transformative leaders who are willing to break rank from the small-mindedness of their parties, and chart a different course that delivers real change.

Zuma has already squandered his credibility and shown himself as out of kilter with the realities of the economy. The major task of pushing for structural reforms in the economy and to restore stability lies with the minister of finance, who ideally should have relative autonomy from the president and able to corral his cabinet colleagues to behave responsibly. Disappointingly, Malusi Gigaba, the new minister, started on a bad footing, peddling rhetoric and taking ambiguous and contradictory positions in his early days in office.

So, what would a package of reforms look like? Government needs to send a clear and strong message about the direction of economic policy. This must be followed by a bold set of actions that could immediately restore confidence and gain the support of the private sector. There’s also a need to restructure state-owned enterprises, improve efficiencies and restore good corporate governance. ![]()

- Mzukisi Qobo is deputy chairman and South African research chairman on African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, University of Johannesburg

- This article was originally published on The Conversation