“The Maxforce” is the European Union team that ordered Ireland to collect billions of euros in back taxes from Apple, rattled the Irish government, and spurred changes to international tax law. You’d think it might have earned the name by applying maximum force while investigating alleged financial shenanigans. It didn’t. It’s just led by a guy named Max.

A European Commission official gave the nickname to the Task Force on Tax Planning Practices in honour of its chief, Max Lienemeyer, a lanky, laid-back German attorney who rose to prominence vetting plans to shore up struggling banks during Europe’s debt crisis.

Since its launch in 2013, the Maxforce has looked at the tax status of hundreds of companies across Europe, including a deal Starbucks had in the Netherlands, Fiat Chrysler’s agreement with Luxembourg, and — its largest case — Apple in Ireland.

Lienemeyer’s team of 15 international civil servants pursued a three-year investigation stretching from the corridors of the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, to Ireland’s finance ministry and on to Apple’s leafy headquarters in Cupertino, California. Much of it outlined for the first time here, this story chronicles a growing clash between Europe and the US and a shift in the EU’s approach to the tax affairs of multinationals.

The Maxforce concluded that Ireland allowed Apple to create stateless entities that effectively let it decide how much — or how little — tax it pays. The investigators say the company channelled profits from dozens of countries through two Ireland-based units. In a system at least tacitly endorsed by Irish authorities, earnings were split, with the vast majority attributed to a “head office” with no employees and no specific home base — and therefore liable to no tax on any profits from sales outside Ireland. The US, meanwhile, didn’t tax the units because they’re incorporated in Ireland.

In August, the EU said Ireland had broken European law by giving Apple a sweetheart deal. It ordered the country to bill the iPhone maker a record €13bn in back taxes, plus interest, from 2003 to 2014. One example the commission cites: in 2011, a unit called Apple Sales International recorded profits of about €16bn from sales outside the US. But only €50m were considered taxable in Ireland, leaving €15,95bn of profit untaxed, the commission says.

Though the EU says its goal is “to ensure equal treatment of companies” across Europe, Apple maintains that the commission selectively targeted the company. With the ruling, the EU is “retroactively changing the rules and choosing to disregard decades of Irish law”, and its investigators don’t understand the differences between European and US tax systems, Apple said in an 8 December statement.

The decision sparked a political crisis as left-leaning members of Enda Kenny’s fragile minority administration saw a potential bonanza for taxpayers that the world’s richest company could well afford

Apple, which has some 6 000 workers in Ireland, says its Irish units paid the parent company a licensing fee to use the intellectual property in its products. The Irish companies didn’t own the IP, so they don’t owe tax on it in Ireland, Apple says, but the units will face a US tax bill when they repatriate the profits.

Apple expects to pay about 26% of its earnings in tax for the most recent fiscal year and has set aside some US$32bn to cover taxes it says it will face should overseas income be returned to the US. “This case has never been about how much tax Apple pays, it’s about where our tax is paid,” the company said. “We pay tax on everything we earn.”

Ireland on 9 November appealed the commission’s ruling at the EU general court in Luxembourg, arguing it has given Apple no special treatment. Irish finance minister Michael Noonan has said he “profoundly disagrees” with the ruling and that Ireland strictly adheres to tax regulations. The government says Ireland has no right to tax non-resident companies for profits that come from activities outside the country.

“Look at the small print” on an iPhone, Noonan said after the EU released its ruling in August. “It says designed in California, manufactured in China. That means any profits that accrued didn’t accrue in Ireland, so I can’t see why the tax liability is in Ireland.”

In the coming weeks, the EU is expected to publish details of the Maxforce investigation. At about the same time, Apple will likely lodge its own appeal in the EU court. Though Apple will have to pay its tax bill within weeks, the money will be held in escrow, and the issue will probably take years to be resolved.

This story is based on interviews with dozens of officials from the EU, Ireland and Apple, though most didn’t want to speak on the record discussing sensitive tax matters. A Maxforce representative declined to make Lienemeyer available for an interview. Ireland’s Office of Revenue Commissioners (its tax agency) says it can’t comment on specific companies.

At the hearing, Arizona Republican John McCain castigated Apple as “one of the biggest tax avoiders in America”

Lienemeyer began assembling the Maxforce in late spring of 2013 with a mandate of scrutinizing tax policies across Europe in search of any favoritism. Direct subsidies or tax breaks to court a specific company are illegal in the EU to prevent governments aiding national champions. His first hire — the person who would oversee the Apple probe — was Helena Malikova, a Slovak who had worked at Credit Suisse in Zurich. He quickly added Kamila Kaukiel, a Polish financial analyst who had been at KPMG, and Saskia Hendriks, a former tax policy adviser to the Dutch government.

As the four initial members began their investigations, they got a head start from a US senate probe of the tax strategies of American multinationals. The senate’s permanent subcommittee on investigations said Apple shifted tens of billions of dollars in profit into stateless affiliates based in Ireland, where it paid an effective tax rate of less than 2%.

At 9.30am on 21 May 2013, senators gathered in room 106 of the Dirksen Office Building. Included in the evidence presented that day was a 2004 letter from Tom Connor, an official at Ireland’s tax authority, to Ernst & Young, Apple’s tax adviser. Connor’s question: a unit of the tech company hadn’t filed a tax return — was it still in business? E&Y responded two days later that the division was a non-resident holding company with no real sales. “There is nothing to return from the corporation tax standpoint,” E&Y wrote. The senate exhibits didn’t include Connor’s response if there ever was one.

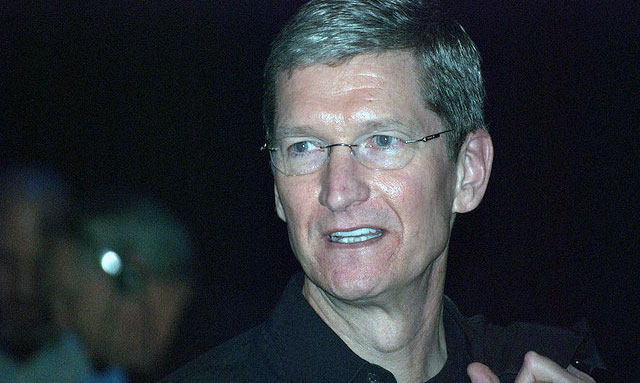

At the hearing, Arizona Republican John McCain castigated Apple as “one of the biggest tax avoiders in America”. Democrat Carl Levin of Michigan peered over the glasses perched on the tip of his nose and said Apple uses “offshore tax strategies whose purpose is tax avoidance, pure and simple”. Crucially, though, Levin told the crowded room that under US law, there was little the panel could do to force Apple to pay more tax. Apple CEO Tim Cook passionately defended the company’s actions, telling the senators: “We don’t depend on tax gimmicks.”

While the Irish government remained bullish in its public statements, saying Apple hadn’t received any favours, behind the scenes tensions were rising

The senate revelations raised eyebrows at the Maxforce’s office in Madou Tower, a 1960s high-rise in the rundown Saint-Josse neighborhood of Brussels. Three weeks after the senate hearing, Lienemeyer’s team asked Ireland for details of Apple’s tax situation. The Irish tax authorities soon dispatched a representative carrying a briefcase filled with a bundle of bound pages. The Irish could have simply sent the material via e-mail, but they were cautious about sharing taxpayer’s information with the EU and have a ground rule to avoid leaks: never send such documents electronically.

While the Irish government remained bullish in its public statements, saying Apple hadn’t received any favours, behind the scenes tensions were rising. Through the summer of 2013, the finance ministry assured government ministers that the EU investigation would amount to nothing, according to people familiar with the discussions. But those assertions seemed less confident than earlier communications. There was a sense that Apple had worked out its Irish tax position in a vastly different era, and no one remembered many details of the negotiations decades earlier.

In 1980, the four-year-old company — the Apple III desktop had just been released — created several Irish affiliates, each with a different function such as manufacturing or sales, according to the senate report. Under Irish laws dating to the 1950s designed to shore up the moribund post-war economy, as a so-called export company Apple paid no taxes on overseas sales of products made in Ireland.

To comply with European rules, Ireland finally ended its zero-tax policy in 1990. After that, Apple and Ireland agreed that the profit attributed to a key Ireland-based unit, the division discussed in Tom Connor’s letter, be capped using a complex formula that in 1990 would have resulted in a taxable profit of $30m-$40m.

An Apple tax adviser “confessed there was no scientific basis” for those figures, but that the amounts would be “of such magnitude that he hoped it would be seen as a bona-fide proposal”, according to notes from a 1990 meeting with the Irish tax authority cited by the EU. The equation didn’t change even as Apple began assembling the bulk of its products in Asia.

At a San Francisco event to promote Irish entrepreneurs, governor Jerry Brown quipped that he had thought Apple “was a California company”, but according to tax returns, “they’re really an Irish company”

Ireland and Apple started to make changes a few months after the Maxforce began looking into their tax relationship. In October 2013, finance minister Noonan announced he would close the loophole that let stateless holding companies operate out of Ireland. The EU said Apple changed the structure of its Irish units in 2015, which the company says it did to comply with the shift in Irish law.

As the Maxforce stepped up its probe in June 2014, Irish prime minister Enda Kenny was wooing potential investors in California. At a San Francisco event to promote Irish entrepreneurs, governor Jerry Brown quipped that he had thought Apple “was a California company”, but according to tax returns, “they’re really an Irish company”.

With Lienemeyer’s team digging further into the issue, Apple’s concern deepened. In January 2016, CEO Cook met with Margrethe Vestager, the EU competition chief — and Lienemeyer’s ultimate boss — on the 10th floor of the Berlaymont building, the institutional headquarters of the European Commission in Brussels.

Vestager, a daughter of two Lutheran pastors, has a reputation for being even-handed but tough, cutting unemployment benefits while advocating strict new rules for banks when she served as Denmark’s finance minister. While she has acknowledged that her team had little experience with tax rulings — in a November interview with France’s Society magazine, she said, “We learned on the job” — Vestager says enforcement of EU rules on taxation is a matter of “fairness”.

In the meeting with Cook, she quizzed him on the tax Apple paid in various jurisdictions worldwide. She told the Apple executives that “someone has to tax you”, according to a person present at the meeting. In a 25 January follow-up letter obtained by Bloomberg, Cook thanked Vestager for a “candid and constructive exchange of views”, and reasserted that Apple’s earnings are “subject to deferred taxation in the US until those profits are repatriated”,

Subsequent correspondence became more heated. On 14 March, Cook wrote to Vestager that he had “concerns about the fairness of these proceedings”. The commission had failed to explain fully the basis on which Apple was being investigated, and the body’s approach was characterized by “inconsistency and ambiguity”, Cook said.

Facing a potential revolt that could bring down the government, Kenny and Noonan eventually bowed to demands for a review of the country’s corporate tax system

Apple contended that the EU had backtracked on a 2014 decision recognising that its two Irish subsidiaries were not technically resident in Ireland, and therefore only liable for taxes on profits derived from Irish sources. Now, Cook said, it seemed the commission was intent on “imposing a massive, retroactive tax on Apple by attributing to the Irish branches all of Apple’s global profits outside the Americas”.

“There is no inconsistency,” an EU spokesman said in a 15 December statement. Only a fraction of the profits of the subsidiaries were taxed in Ireland, the statement said. “As a result, the tax rulings enabled Apple to pay substantially less tax than other companies, which is illegal under EU state aid rules.”

Cook’s entreaties did little to sway Vestager, and in August she phoned Noonan to tell him the results of the Maxforce investigation: the commission was going to rule against Ireland. Late in the afternoon of 29 August, Irish officials began hinting to reporters that Apple’s tax bill amounted to billions and “could be anything”. At noon the following day, Vestager told a packed press conference in Brussels that the commission had decided Apple owed Ireland €13bn.

Though that would be equivalent to 26% of the 2015 national budget, Ireland didn’t want the windfall, saying the ruling was flawed because the country hadn’t given Apple any special treatment. The decision sparked a political crisis as left-leaning members of Enda Kenny’s fragile minority administration saw a potential bonanza for taxpayers that the world’s richest company could well afford. Even as Noonan toured television studios vowing to appeal the decision, independent lawmakers demanded that Ireland take the money.

Facing a potential revolt that could bring down the government, Kenny and Noonan eventually bowed to demands for a review of the country’s corporate tax system. But they said they would fight the case, and on 7 September, Irish lawmakers overwhelmingly backed the motion for an appeal.

Officials from Lienemeyer’s team and other EU offices say they have gathered tax information on about 300 companies, looking for what they deem to be favourable treatment by governments across Europe. While they don’t expect all of those to yield payoffs as hefty as that from their investigation of Ireland and Apple, they say a worrying number require the kind of maximum force that the Maxforce can apply.

“We focus on outliers where you’re looking at something that is off the radar screen,” Lienemeyer’s boss, 50-year-old Dutchman Gert-Jan Koopman, who is in charge of state-aid enforcement at the EU, said at a Brussels conference in November. “If you’re paying a fair amount of tax then there is absolutely nothing to worry about.”

- Reported with assistance from Stephanie Bodoni and Aoife White