“In just over 30 years, humans will be able to upload their entire minds to computers and become digitally immortal,” said computer scientist and futurist Ray Kurzweil at the Global Futures 2045 International Congress in 2013.

Without even considering the ethical, philosophical, social or legal scope of such a statement, it’s important to consider if it actually makes any sense. To try to give an educated guess, we have to move away from computer science and look at what biology and neuroscience can teach us.

In his book Being There: Putting Brain, Body and World Together Again, Andy Clark explains that:

The biological mind is, first and foremost, an organ for controlling the biological body. Minds make motions, and they must make them fast — before the predator catches you, or before your prey gets away from you. Minds are not disembodied logical reasoning devices.

To better understand this assertion, it’s essential to know that our bodies are literally covered with sensors — chemical, mechanical, visual, thermal, proprioceptive (perception of the body), noniceptive (perception of pain). All of them inform the brain about the outside world (exteroception) and the inner world (interoception), allowing it to regulate the body. The majority of our brain is actually dedicated to the processing of sensory information, and the largest part of that is devoted to visual information, occupying the entire occipital lobe and large parts of the temporal and parietal lobes. We are mostly visual beings who, incidentally, think.

If someone wants to “upload his entire mind to a computer”, the problem of sensors must be solved. A quick and dirty solution could be to not worry about them and just pretend that all sensory neurons would remain silent forever. However, 50 years ago, Donald O Hebb conducted a series of experiments to study the effects of sensory deprivation. He generously paid students to recline 24/7, taking care to deprive them of most of their senses using glasses, helmets, gloves and so on. The majority of the students abandoned the experiment after two or three days because they were no longer able to develop coherent thoughts and began to suffer from auditory and visual hallucinations. The experiences evoked considerable interest from the CIA (which financed the original study) and they later “improved” the process up to the point where it was transformed into an instrument of psychological torture.

The body electric

Consequently, if we want to “upload our brain” without going insane, it’s imperative for the uploaded brain to be connected to an artificial body that can perceive the outside world and act on it. But what kind of artificial body do we have today? Robotic bodies where retinas are replaced by cameras and muscles by motors? To some extent, yes, but this solution would be only a pale replica, far from the complexity and intelligence of the human body, as nicely explained by Rolf Pfeiffer and Josh Bongard’s book How the Body Shapes the Way We Think.

During childhood, a brain learns through experience to control its body and to leverage its specifics. For example, consider the fingertips, which are sufficiently soft and sensitive that we can easily grasp small objects. There’s no need for the brain to send a precise command — the intelligence is in the body itself. Imagine trying to do the same thing with thimbles over each finger, and you will understand how your body automatically solves a number of problems all by itself.

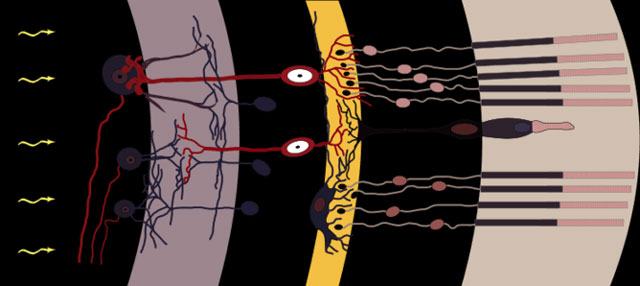

What about the artificial eyes we’d need? Even though high-resolution cameras now exist, the eyes we’re born with each have approximately 5m cones and 100m rods, plus the various “preprocessing” stages, from the horizontal, bipolar, amacrine and ganglion cells. We are indeed very far from being able to reproduce a full artificial retina, even though some amazing research in Paris has succeeded in helping the vision-impaired see again.

As a first step, we could therefore use those simplified robotic bodies with their reduced sensory and motor skills. Would it affect our minds? Yes. Our cognition depends on the interactions we have with the world, and this interaction is conveyed by both our perceptions and our actions. If you change them, you also change the sensory experience of the world as well as its underlying logic. Cognition is embodied.

Look out for part two of this article tomorrow.![]()

- Nicolas P Rougier is chargé de recherché at Inria, the French Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation

- This article was originally published on The Conversation