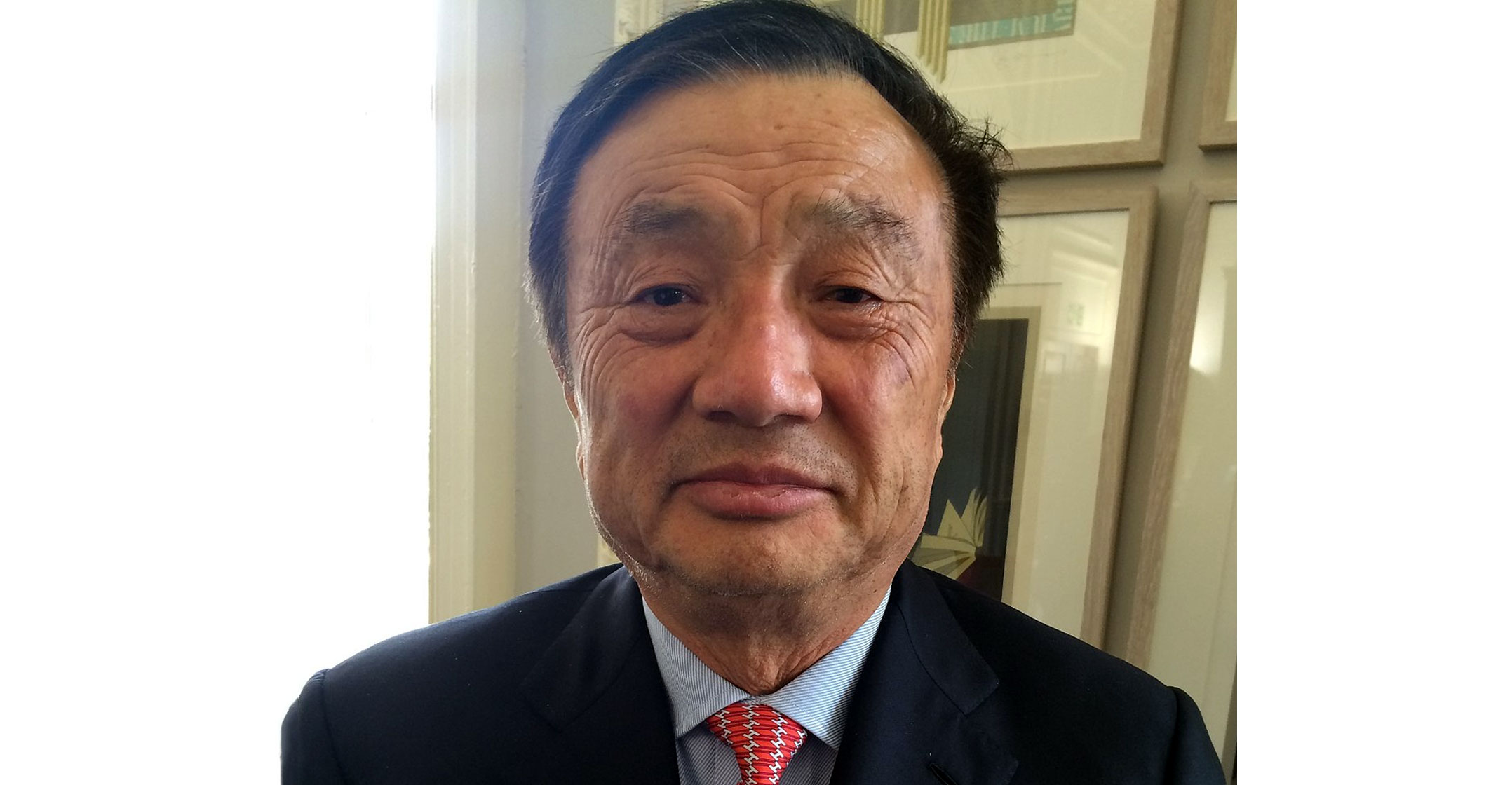

In the days after the US government said it would bar Huawei Technologies from buying vital American components, the Chinese company’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, pulled together an emergency meeting of his top lieutenants at its headquarters in Shenzhen.

In the days after the US government said it would bar Huawei Technologies from buying vital American components, the Chinese company’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, pulled together an emergency meeting of his top lieutenants at its headquarters in Shenzhen.

In a large conference room, the billionaire asked for a report from the head of each business unit on how they would be affected by the Trump administration’s ban, which blocks US companies from supplying everything from semiconductors to software. Their assessments were dire. “We thought we had lost the world,” said Will Zhang, who attended as president of corporate strategy.

It turns out they were far too pessimistic. Huawei recorded an 18% rise in sales to a new high of 850-billion yuan (US$122-billion) last year, although that was down from about 23% in the first half and missed its own internal targets. Company projections for 2020 are similar. Huawei holds the enviable position of being the world’s largest supplier of communications equipment to telecoms operators and the largest smartphone maker globally after Samsung Electronics.

Huawei isn’t just surviving; it’s actually thriving in some areas. The question is for how long. Last week, executives warned in a New Year’s memo that survival itself is a priority, urging employees to brace for a difficult 2020. Inventories stockpiled months in advance of the May blacklisting are drying up. The company can no longer count on momentum alone to drive the business, rotating chairman Eric Xu warned.

How Huawei survived the US blacklisting could prove a case study in unintended consequences and a vast shift underway in global IT production. Huawei is a big customer for all of its suppliers, and a few actually cut ties after the blacklisting. Others lost out to rivals in Japan and South Korea. But American companies with extensive global operations, including Microsoft and chip maker Micron Technology, found legal ways around the ban, leaning on production outside the US so Huawei-destined products wouldn’t be hit. Huawei itself put armies of engineers to work redesigning products to reduce its reliance on American parts.

Surprising implications

Trump’s attack also had surprising implications for Huawei’s brand. A few countries, like Australia, agreed with the US president’s assessment and barred its equipment from their networks. But in the rest of the world, Huawei’s name recognition soared. After labouring in obscurity for decades, the maker of digital piping was suddenly front-page news everywhere. Beyond the US and its close allies, telecoms operators wanted to find out what all the fuss was about. In China, consumers and carriers rallied to Huawei’s side in response to what they saw as unfair persecution, driving a sales boom. The Trump sanctions in some ways validated Huawei’s ability to develop cutting-edge technology, from 5G networking gear to AI chips.

“It’s quite a stupid thing the US is doing,” said Zhang, a key architect of Huawei’s global ambitions and efforts to mitigate the impact of American sanctions. “They are confused about how this business works.”

Huawei is a global Goliath with revenues more than General Electric or Boeing. In just three decades it’s grown from an obscure reseller of switchboards into one of the world’s biggest private companies, with businesses from telecoms to cloud computing to cybersecurity. After ploughing billions into research, the company is now among China’s top recipients of international patents, edging out rivals Nokia and Ericsson in a technology that underpins applications from robotics to AI.

Huawei started to tap overseas markets in the late 1990s, dispatching sales representatives to Russia, Southeast Asia and Africa, where competition was less intense than in developed arenas. It used lower pricing as a wedge to gain entry, then tried to one-up its rivals on round-the-clock customer service. One of its earliest markets was Malaysia, where it wielded that formula to great effect. “I was asked by one of the board members to consider Huawei. I remember my response at the time was, I don’t want to waste my time,” Jamaludin bin Ibrahim, CEO of Malaysian wireless carrier Axiata, said. “When they started initially, it was price that gave us confidence.”

Once Huawei secured the contract, they pulled out the stops. According to Jamaludin, Huawei’s then rotating-CEO would get personally involved in Axiata problems or maintenance issues. When friction developed between Axiata ground staff and Huawei workers assigned to the contract, Jamaludin called the Chinese company’s rotating CEO and within two days, all the Huawei employees had been reassigned, he said, describing rarely disclosed, behind-the-scenes details of how Huawei conducts business. Today, Huawei gear occupies about 80% of Axiata’s core network, he said. While the equipment isn’t necessarily always the most capable or advanced, the Chinese company has other things going for it. “The combo of tech, customer service, support and price is what makes it stand out,” Jamaludin said.

Cultivating such deep ties in countries like Malaysia appears to have paid off. Last May, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad said the Southeast Asian country will use Huawei’s gear “as much as possible” as they offer “tremendous advance over American technology”.

Huawei executives like to trumpet instances where employees go above and beyond to get the job done. Sometimes, they also seize the initiative. In 2003, without Ren’s blessing, some Huawei executives decided to venture into mobile phones. It wasn’t until the early 2010s that Huawei made its first smartphone, and early models were no-frills, basic affairs that competed on price — much as its networking gear once did. But within half a decade, Huawei had used a combination of savvy marketing (partnering with Leica in 2016 on cameras was a master-stroke) and research to move up the value chain and challenge Apple and Samsung.

Diversification

It’s in smartphones that evidence of Huawei’s diversification efforts emerge. Launched last spring, the marquee Huawei Mate 30 Pro handset uses communications modules from Japanese supplier Murata Manufacturing and contains a number in-house components. This contrasts with the Mate 20 Pro released a year earlier that relied on components from US wireless semiconductor manufacturer Skyworks Solutions.

Huawei’s smartphone business is now the world’s number two, growing shipments 16.5% to a record 240 million units in 2019. Much of that growth came from China, where Trump’s sanctions have little effect since the Google apps it’s shut out of can’t be used anyway. Even some senior Huawei executives hadn’t expected the smartphone business, which today contributes about half of revenue, to survive the sanctions, not to mention expand.

But this year may not be so rosy. “Huawei faces strong challenges in 2020, especially in the smartphone business,” said IDC analyst Will Wong. “Its retail channel will face immense pressure as some buyers may turn to Samsung or another brand since the latest Huawei phones lack support from Google Mobile Services.”

Another area the blacklisting will severely impact is the enterprise business, which makes servers and sells smart city solutions to clients around the world. The Entity List cut Huawei off from the Intel x86 processors it needed and Huawei’s supply chain managers couldn’t source alternatives because there aren’t any with comparable performance and availability. Huawei originally anticipated as much as $8-billion in server revenue in 2019. The final total was only half as much. “The server is not the core product. But every project you have, there will be some servers,” Zhang said.

Another area the blacklisting will severely impact is the enterprise business, which makes servers and sells smart city solutions to clients around the world. The Entity List cut Huawei off from the Intel x86 processors it needed and Huawei’s supply chain managers couldn’t source alternatives because there aren’t any with comparable performance and availability. Huawei originally anticipated as much as $8-billion in server revenue in 2019. The final total was only half as much. “The server is not the core product. But every project you have, there will be some servers,” Zhang said.

Longer term, it could also lose access to chip design tools from US-based companies such as Synopsys and Cadence Design Systems, which would undermine its aspirations to become a player in the semiconductor industry — a key aspect of any effort to replace American technology.

Still, the real battle from 2020 onward will be in 5G. The company started initial research on the standard as early as 2009, when even 4G was years from commercialisation. It assigned more than $600-million to the project in the following five years, according to the company’s website. That surged to $1.4-billion between 2017 and 2018.

The US government has long worried Huawei’s 5G capabilities pose a threat to national security. It warned in 2018 that Huawei owned 10% of worldwide essential 5G patents and deep involvement in international standards-setting could weaken US companies’ negotiating power. Huawei has inked more than 60 5G contracts globally, deputy chairman Ken Hu said in September. Washington continues to try and persuade allies to boycott Huawei gear in core networks — if successful, that could severely crimp its future prospects in a swathe of technologies and hamper efforts to grab a slice of hundreds of billions of dollars in projected network spending.

“Design and software are really the biggest challenges,” said Paul Triolo of the Eurasia Group. But “they have surprised people with their ability to re-engineer products. They’re in it for the long haul.”

There’s also the chance that Washington will tighten the screws. The US government is said to be weighing new limits on sales of chips and other vital components to Huawei. Zhang said the company has decided to tune out the noise of US-Chinese relations. “This blacklisting has changed the whole perception of globalisation,” said Zhang. “The world is not flat anymore, everybody agrees and will try to adopt that approach. The suppliers and Huawei ourselves will try to adapt to the new geopolitical complex.” — Reported with assistance from Peter Elstrom, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP