Technology often needs a “killer app” to gain mass market appeal.

For the touch screen, it was the iPhone; for wearables, the Fitbit. Augmented reality games have been around for more than a decade, so what was it about Pokémon Go that allowed it to become a global phenomenon?

We believe it can be attributed to three core social components of the game: the blending of the virtual and the real, geo-location and the success of existing Pokémon culture.

The first time we heard about Pokémon Go was via a few Facebook posts with screenshots of Pokémon on the streets or sitting beside friends. This is the core strength of augmented reality apps, the ability to alter the physical world by adding virtual components.

Millions of dollars have been spent on technology for aligning the physical world and virtual contents. Tracking issues have taken up 20% of the research effort in the augmented reality community around the world for the past decade.

Microsoft’s latest augmented reality headset, the HoloLens, uses a series of cameras to physically map out the entire environment around the user to accurately place virtual objects.

Pokémon Go does not have this level of sophistication. When players come across a Pokémon character in Pokémon Go, the game superimposes it over the camera view.

We tested the feature and noticed we needed to play around with the phone to get the perfect angle for the screenshot. So although the tracking may not be sophisticated, a user can, with minimal effort, quickly make the Pokémon appear as if they are part of the physical world.

Some players get creative with these poses, which are shared widely on social media platforms. We believe the “shareability” of these images contributes hugely to the success of the game.

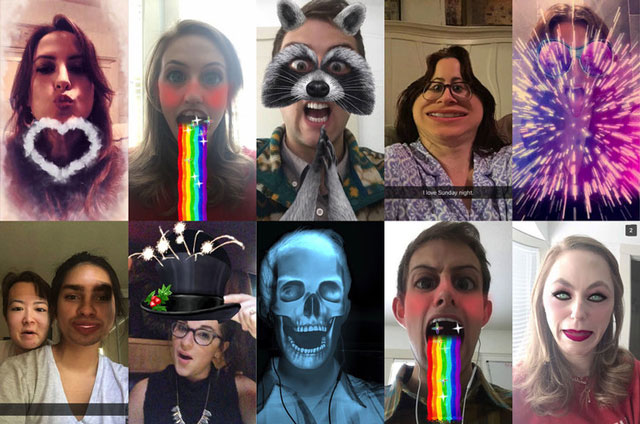

Snapchat, the phenomenally successful messaging application with more 100m users, also taps into the social “shareability” of images that blend the virtual and the real.

Gather some teenagers in a room together and it will not be long before the room will be filled with giggles and cries as they swap “snaps” with augmented features overlaid over theirs via Snapchat filters.

Although there has been keen research interest in augmented reality as a means of treating phobias and the pain associated with phantom limbs, to date there has been little research focus on the psychological aspects of our fascination with blended imagery.

Researchers studying the customisation of avatars, a graphical representation of a person’s alter ego or character in computer games, have found that the ability to manipulate physical features such as hair colour, or to superimpose animal features over human forms, is critical for an avatar to appeal to a user.

There are clear parallels here to the success of augmented reality app features such as Snapchat filters. Pokémon Go screenshots also seemingly tap into this desire for a personal connection to the virtual world.

Pokémon Go, you go!

Pokémon Go requires you to walk around to hunt down Pokémon. This aspect of the game is not new, as similar games in the past have utilised this, including Niantic’s own Ingress. In fact, Pokémon Go uses the same Ingress platform.

Many see this as a positive example of games that encourage people to exercise. We see it more as a social success as it highlights the power of an augmented reality platform as a shared, social experience.

The success of this aspect of the game can be gauged by following the various reports of organised Pokémon Go events with thousands of registered participants.

Virtual reality, by comparison, is a very personal experience. There have been many previous attempts at introducing social interactions into a virtual reality environment. Second Life was released in 2003 and after a decade had more than a million users.

Pokémon Go had already dwarfed this user count within 48 hours of release. Reports suggest it has eclipsed the daily user counts of major social network and dating services such as Tinder and Twitter.

A money earner

A final aspect of the success of Pokémon Go is undoubtedly its ability to tap into an established pop culture phenomenon.

According to Nintendo, as of the end of May 2016, it had sold more than 280m units of Pokémon-related software, earned box office revenue of ¥76,7bn (about R10,4bn), and shipped over 21,5m cards (as of September 2015).

The company estimates the total worldwide market size of the Pokémon franchise to be more than ¥4,8 trillion (about R655bn).

With a market this big, there was an eager community of Pokémon fans waiting for an app such as Pokémon GO to launch.

There are clear parallels here to another smash hit smartphone game, Kim Kardashian: Hollywood. This game traded on the celebrity credibility of the Kardashians and used social gaming methods and the promise that you might even become one of Kim’s friends, at least within the confines of the game.

A March Forbes article estimates that Kim Kardashian: Hollywood has earned the star around US$20m.

Given the success of Pokémon Go, Nintendo executives can be assured that the Pokémon franchise’s level of success, and its share price, is set to continue upward.

This ability to tap into the established worldwide community of Pokémon fans was the final ingredient necessary to establish Pokémon Go as the “killer app” for augmented reality gaming.

So, to make a killer app, just add social.![]()

- Thuong Hoang is research fellow, University of Melbourne, and Steven Baker is research fellow, Microsoft Centre for Social Natural User Interfaces, University of Melbourne

- This article was originally published on The Conversation