Too rich for debt relief available to most African nations and hobbled by its politics, South Africa is facing a public financing crisis.

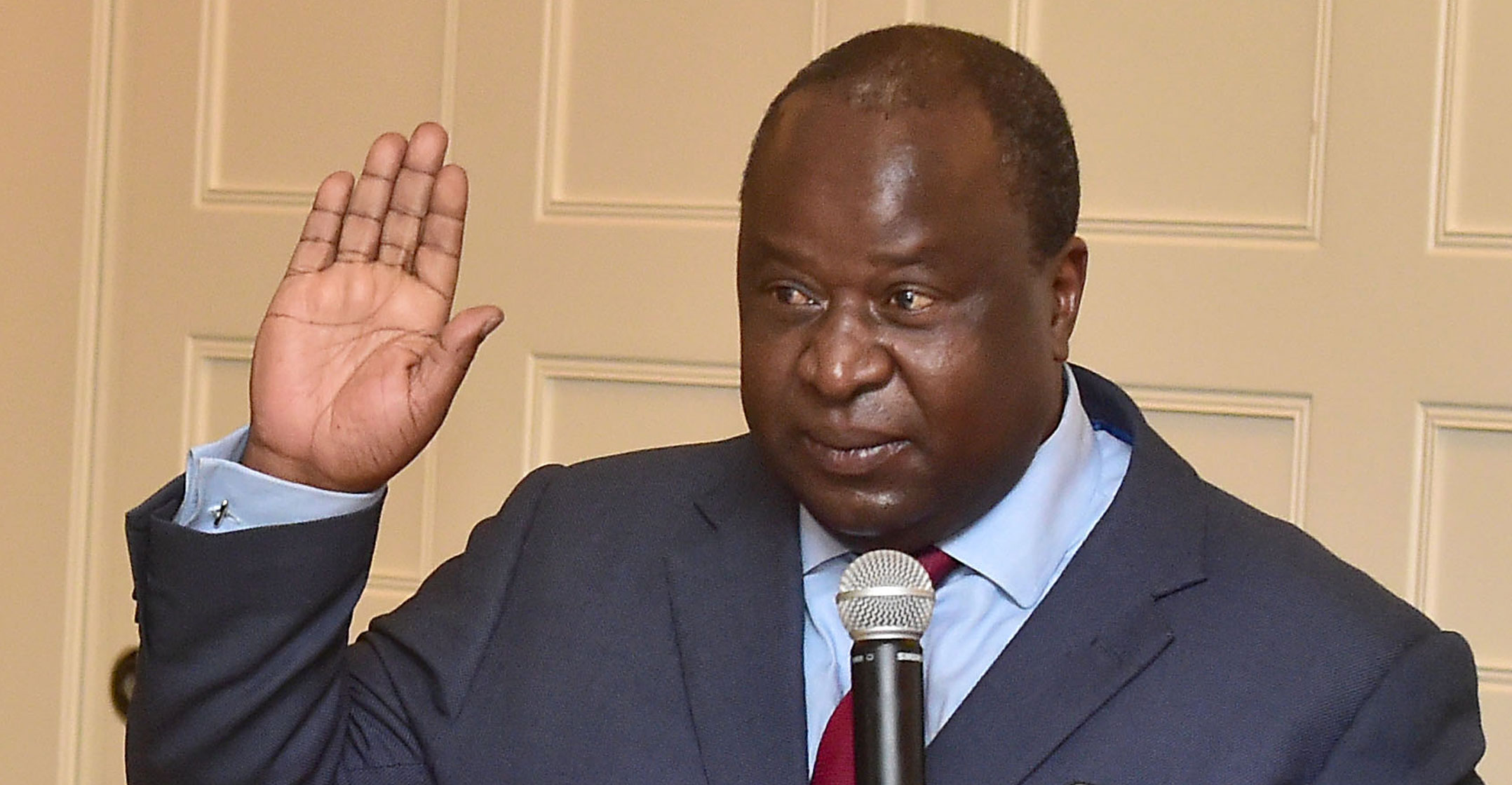

Debt levels will continue to rise, peaking in 2024 and only dipping back below 80% of GDP by 2028, according to the supplementary budget finance minister Tito Mboweni presented on Wednesday. And that’s a best-case scenario, where the government takes active steps to stabilise the trajectory and revives an economy which the treasury projects will contract by 7.2% this year.

“Debt is our weakness,” the minister said his budget speech. “Even as South Africa responds to the current health and economic crisis, a fiscal reckoning looms. The public finances are dangerously overstretched.”

Mboweni’s adjustment budget and forecasts accounted for the impact wrought by the coronavirus pandemic as well as the nation’s response so far: a R500-billion stimulus package. But the former Goldman Sachs Group adviser’s plans to trim spending and enact structural reforms face stiff opposition, including from labour groups aligned with the ANC.

South Africa’s fiscal decline accelerated over the past decade as loss-making state-owned companies including Eskom and South African Airways received a series of bailouts and the government repeatedly failed to rein in public sector wages.

The country lost its investment-grade credit ratings, which exacerbated the problem by boosting borrowing costs at a time when debt repayments already crowd out spending on development.

G20

Yet despite the rapid deterioration in its finances, South Africa’s status as a middle-income country with a relatively large GDP bars it from coronavirus debt-relief initiatives other countries in Africa can lean on in such a crisis. It is, in fact, a member of the Group of 20 developed economies, which has pledged to suspend payments on official loans for the world’s poorest nations, most of them in Africa.

Even before the pandemic, South Africa was stuck in its longest downward economic cycle since World War 2 and the economy was in recession. Revenue collection is expected to plunge as a lockdown that began in March to curb the spread of the virus weighs on activity.

“We were in a fiscal crisis before the virus,” said Dawie Roodt, chief economist at Efficient Group in Pretoria.

Plans to reduce the public-sector wage bill, which has climbed by 40% over the last 12 years, have stalled in the face of opposition from politically influential labour groups. Reforms proposed in a national treasury policy paper, forecast to lift economic growth by two to three percentage points and create more than one million jobs over a decade, remain dormant.

Plans to reduce the public-sector wage bill, which has climbed by 40% over the last 12 years, have stalled in the face of opposition from politically influential labour groups. Reforms proposed in a national treasury policy paper, forecast to lift economic growth by two to three percentage points and create more than one million jobs over a decade, remain dormant.

The pandemic has forced the ruling party to break a long-held resistance to borrowing from the International Monetary Fund, requesting a US$4.2-billion loan to cover virus-related spending.

But warnings it may require additional budget support and have to follow a structural reform programme mandated by the Washington-based lender are unlikely to be heeded ahead of municipal elections next year, said Ralph Mathekga, a political analyst and author of books about South African politics.

“Populist measures become what sustains them election on election,” Mathekga said of a party that’s ruled the nation uninterrupted since 1994. “It is highly unlikely that they can undertake austerity measures.” — Reported by Prinesha Naidoo, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP