Motorists and taxpayers appear set to become the cash cow to allow the government to reduce its percentage of the funding of the multibillion-rand expansion of the Gautrain.

Gautrain Management Agency (GMA) CEO William Dachs said on Monday: “We firmly believe the people in cars don’t pay their fair share in terms of the taxes that they pay and the failure of the e-tolls system has perpetuated that problem.”

Dachs was commenting on the GMA’s engagement with national treasury about the sources of funding for the Gautrain expansion project and the need to move people off the roads and away from carbon-intensive modes of transport during a virtual panel discussion on the “Future of Rapid Rail in Gauteng and its Impact on Social and Economic Development”.

He said the GMA started its engagement with treasury on the funding of the expansion with “a clean sheet of paper and to look at all the possible sources”.

“We looked at everything from general tax increases to fuel taxes to fuel levies to congestion charges, which haven’t happened in South Africa yet, all the way through to the more traditional funding sources,” said Dachs.

“We also looked at developer charges, bearing in mind that people who develop around existing Gautrain stations have seen massive increases in the values of their properties.”

Detailed analysis

“We then did a quite detailed analysis of what each source could bring and which one of them would be the most viable,” he said.

Dachs did not comment on which of these sources was the most viable but said: “We would be looking at a blend of national government funding, provincial government funding, people who use the trains, private developers contribution as well as those who invest in the train itself.”

He confirmed that vehicle licence fees had been considered during the GMA’s engagement with treasury but stressed that: “It’s not an infinite source.”

“Gauteng can’t become uncompetitive in terms of its vehicle licences compared to other provinces but there is a strong case to be made there,” he said.

Dachs said there is a strong willingness from private-sector developers to invest in new stations provided they are transit-orientated developments from which they can get a return.

He said they were obviously also looking at getting private sector investment in the infrastructure itself “because the people who use the trains will pay for them”.

Dachs stressed that there is a “massive misconception” that the people who use the current Gautrain are massively subsidised in terms of the operations cost, which is untrue. He said there was a “close to 100% recovery” of the operating costs of the Gautrain from the money people pay to use it although “Covid-19 messed that up”.

Dachs said this high operating cost recovery rate goes a long way toward the long-term financial sustainability of the Gautrain. “The government subsidy to date has really been around the capital part of the Gautrain and we would look to continue that going forward,” he said.

Gauteng provincial borrowings and provincial budget allocations via national government accounted for 88% of the total cost of the first phase development of the Gautrain, with private-sector debt only accounting for about 12%.

Reports have suggested the government wants to reduce its funding of the Gautrain expansion to 33% while former GMA CEO Jack van der Merwe said last year the plan was to increase private-sector funding to 33%.

The GMA submitted plans about the Gautrain expansion programme to national treasury in 2017.

Robust engagement

But Dachs stressed on Monday that treasury did not cause a delay in the project and the GMA has had a real, good and robust engagement with treasury about this huge and complex project. He said two issues kept arising during these engagements: how to make it more accessible to more people without compromising its financial sustainability, and how it can be funded.

“It can’t just be 100% government funding. How do we build a private-sector investment in here? How do we encourage people who benefit from a project like this to also contribute to it financially? We have answered those questions. It’s been a two-and-a-half year process in terms of engagement on it and, as we speak, we are just finishing the final study,” he said.

Development Bank of Southern Africa head of transport and logistics Cyprian Marowa said the DBSA is good at bringing together many institutions into the lending space. Marowa said no individual bank can single-handedly develop infrastructure like the Gautrain and the DBSA is seen globally as a good partner for other institutions to come in and be part of the infrastructure projects in South Africa.

He admitted that Covid-19 has been “a spanner in the works” and money generally has become more expensive, with some projects delayed. But Marowa said it is important “to keep your eye on the ball and take a long term view”. If the number of cash flows that could be generated from different aspects of the Gautrain expansion project are aggregated “you find that this would turn out to be a very good project for any investor”.

Transport analyst and economist Ofentse Hlulani Mokwena said there is a need for the government and other funders to be very conscious of the kind of risks they expose themselves to from a funding perspective because this will change the dynamics of their returns.

Mokwena said there will certainly be some controversial funding options and some options that are more attractive and more acceptable to the public. He said this is something the government will have to balance, especially in order to negotiate a good allocation risk. Mokwena added that the key issue is whether there are viable alternatives and whether this service will be attached to the existing system.

“That is going to be crucial because what you want is to be able … to ring-fence financing … and to justify that you have to have public buy-in. That is going to be crucial because with a project of this scale, the last thing you will want is risk on the infrastructure, on the programme, or even at a political level. So, whatever the financing options that are decided on or pursued, the key here is to contain and manage the risk,” he said.

Mokwena said there is also the risk of modal exclusion or parallelism and questioned why there was not a deeper relationship with, for example, bike sharing schemes, minibus taxis and the existing bus services.

New stations, rail

He said these modes of transport are essentially part of the discussion to justify digging into the public financing environment. “It’s not just about the project but being able to manage the public perception, the allocation risk and making sure the project retains its social, economic and political viability. The numbers count but there is a lot more to it,” he said.

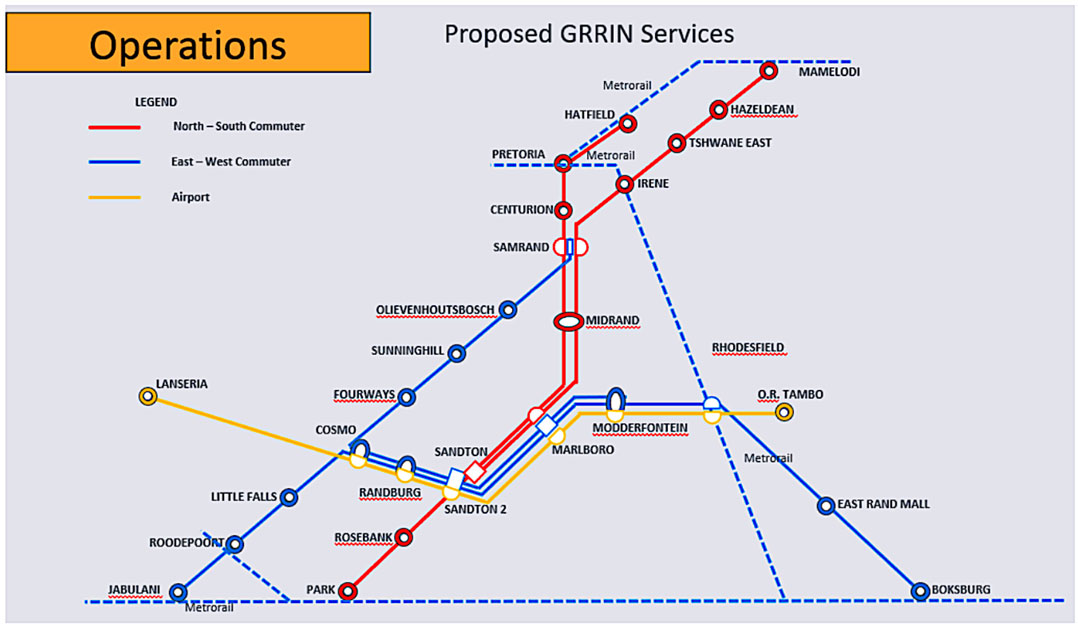

The current Gautrain network comprises 80km of rail along two route links: a link between Tshwane and Johannesburg and a link between OR Tambo International Airport and Sandton. The expansion comprises another 150km of rail and a further 19 stations.

Dachs said the single conclusion the Gauteng provincial government came to in 2014 when it started working on its 25-year integrated transport master plan is that moving people to and from jobs in perpetuity on the roads is not going to work and rail has to be the backbone of a public transport system.

He said the five-phase Gautrain expansion plan was a very ambitious long term plan and this massive build programme will take 20 to 30 years to complete.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission