The SABC has been in the news for all the wrong reasons in recent times. The extent of its woes were laid bare in testimony at the judicial commission investigating allegations of corruption at various state institutions under former President Jacob Zuma.

Witnesses, including former and current SABC, painted a frightening picture of an institution hobbled by financial bankruptcy, corruption, political interference, erosion of editorial independence, and abuse of power and low staff morale.

The SABC has had a long a painful history. For years it was a mouthpiece of the apartheid government. But it was not destroyed after 1994 when South Africa became an inclusive democracy. Rather, the aim was to build it into a strong institution that would contribute to the new South Africa.

After an initial promising start, that project began to fall apart. There’s no question that the SABC has violated its public broadcasting service obligations. And that it continues to place a strain on taxpayers.

The question that needs answering is: what needs to be done to fix it?

It is in the very spirit of democracy and media diversity that the citizens must be exposed to a variety of media types. That’s why it’s perfectly reasonable that a public broadcasting service should co-exist alongside commercial and community media forms.

These should ideally be owned by a wide variety of proprietors, and widely divergent content.

Essential part of the mix

But a public broadcaster is an essential part of the mix. Unlike other media, a typical public service broadcaster has a legislated obligation to be universally geographically accessible; have universal appeal; pay attention to the needs of the minorities such as people living with disabilities; contribute to creation of national identity and sense of community; and, compete on the basis of good programming rather than in numbers or ratings.

Another reason for defending South Africa’s public broadcaster is that the problem lies with the way in which the institution has been run, rather than the underlying concept of a public broadcaster. The problems that afflict the institution affect only some parts of the SABC — and only some people.

It doesn’t make sense to discard the entire institution just because it has attracted people who have failed in their duties, and who have failed to make it the great broadcaster it could be.

One of these failures has been the inability to insulate the institution from vested political interests. Yet a public broadcaster’s primary responsibility — anywhere in the world — is to exclusively serve the interest of the public, and not any political (factional) and commercial interests.

One of these failures has been the inability to insulate the institution from vested political interests. Yet a public broadcaster’s primary responsibility — anywhere in the world — is to exclusively serve the interest of the public, and not any political (factional) and commercial interests.

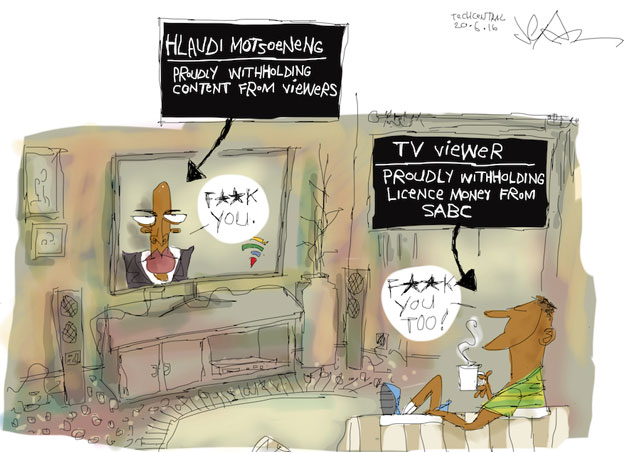

Yet the ruinous eras of both Hlaudi Motsoeneng, the former chief operating officer, and the former news and current affairs MD Snuki Zikalala are just two examples of the calamitous failure to insulate the institution from vested political interests.

Politically, the SABC had a good start in early post-apartheid South Africa under the leadership of Zwelekhe Sisulu, the CEO and Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri, the board chair. Nelson Mandela was the president at the time. His respect for public institutions is legendary.

Sisulu and Matsepe-Casaburri came from the ANC but understood the difference between a public and state broadcaster. Merit was also the primary consideration in choosing the CEO and board chairs.

Even though the Broadcasting Act was only passed in 1999, political will was enough to protect the broadcaster. In addition, the SABC was largely stable, and had money. It used this to commission good quality dramas such as Isidingo, Generations and Yizo Yizo. Its news and current affairs programmes, such as Special Assignment, were produced by seasoned journalists. And it had a solid investigative unit.

But the landscape began to change and the broadcaster’s market share and commercial fortunes began to shrink in the face of scores of community and regional commercial radio stations, a new free-to-air broadcaster, e.tv, and cheaper packages from DStv aimed at the growing black middle class. At the same time, the broadcaster was being politicised. CEOs left before the end of their terms, some with massive golden handshakes.

Political interference

President Thabo Mbeki began to rely on the SABC as the platform on which he could be defended. In 2006, the Sisulu Marcus Report revealed that the broadcaster blacklisted commentators critical of him. The SABC was to hide a clip showing the booing of the deputy president, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. This culture of censorship was continued with the banning of violent protects and insistence on the positive coverage of President Jacob Zuma.

The country needs to devise the legislative means to insulate the SABC — internally and externally — from people who are beholden to (political and commercial) interests other than the public interest. The country cannot afford to lose the SABC.

It is constituted in chapter IV of the Broadcasting Act in defence of the South African public. It is supposed to be a practical platform where people’s constitutional rights — freedom of speech and the right to information — are realised and equally protected.

This role has become increasingly important given the fact that we live in an era of shrinking commercial media newsrooms amid a rise in manipulative forms of political and commercial communications designed to cover up both government and private sector corruption and other malfeasance.

This role has become increasingly important given the fact that we live in an era of shrinking commercial media newsrooms amid a rise in manipulative forms of political and commercial communications designed to cover up both government and private sector corruption and other malfeasance.

We also live in an era known for its preponderance of leisure and entertainment. As a public broadcaster, the SABC has the potential to critically engage South African citizens on serious matters for the common good, and not exploit them in pursuit of profit. The SABC can execute this task comparatively better than any other media. It also has the distinct advantage of reach.

The state broadcaster reaches millions of South Africans, in their own languages. Its physical infrastructure makes it almost universally accessible in a country beset by inequality.

With its 19 radio stations and four television channels, it is better suited to defend the interests of the public than other media. The SABC’s biggest radio station, Ukhozi FM, alone touches the lives of 7.7 million South Africans daily.

In a developing country like South Africa, it is public broadcasting, particularly radio, that provides valuable information that matters in the lives of ordinary people. It can meet the information needs of South Africans, while also providing for the needs of the minorities, whose programmes may not be profitable. As such, an SABC that lives up to the ethos of a public service broadcaster can contribute to national identity and coherence, and a sense of community in a fragile country.

The SABC, like South Africa itself, is a symbol of contradictions. While there are bad people who work for it, there are also many good ones. It’s because of the good people that the broadcaster has survived.

For their sakes, and the country’s democracy, it’s imperative that the government provides the SABC with the necessary financial backing it needs to weather its current financial storms.![]()

- Written by Musawenkosi Ndlovu, associate professor, Centre for Film and Media Studies, University of Cape Town

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence