Former Vodacom Group CEO Alan Knott-Craig’s biography, Second is Nothing, is a riveting — and sometimes explosive — account of the early days of cellular telecommunications in SA.

TechCentral is pleased to publish an exclusive extract from the book, detailing an incident between Vodacom and MTN that ended in a meeting in Nelson Mandela’s office.

Knott-Craig told TechCentral this week that the events were a “testimony to Madiba’s greatness and our pettiness”.

The 1990s witnessed a titanic struggle between Vodacom and MTN over which would emerge as the country’s preferred network provider. For the most part, the competition between the two companies was both open and amicable. Alan had repeatedly expressed his belief in the benefits of free-market competition and his MTN counterpart was of similar mind.

Alan said to the press tongue-in-cheek, “Competition is great. What we fear most is that we will beat MTN out of business and then we won’t have any competition.”

On one occasion, however, this good-spirited rivalry turned into something rather unpleasant. In July 1998, MTN’s Bob Chaphe challenged Alan to pit the quality of Vodacom’s network coverage against that of his own.

“We’ll organise the whole event,” Bob said. ‘The idea is to gather an entourage of technical experts and journalists, including consumer guru, Isobel Jones, to drive through Johannesburg to see which network performs the best. Of course, it will be audited by KPMG to ensure the veracity of the results.”

“No way,” said Alan. “I’m not playing it by your rules. I would rather not be part of a one-sided game. You go and play by yourself. We’ll sit this one out.”

“Scared of the competition, Alan?” Bob laughed.

“Not even a little, boet,” Alan assured him.

Alan wanted nothing to do with the event, which to him appeared little more than a cheap publicity stunt that MTN wanted to engineer to its own advantage. But the event went ahead anyway. With two heavyweights in the ring, the media couldn’t wait for the contest to get started and reported the event in the newspapers at length. Alan was not surprised to hear soon after that MTN had come out on top, but still resolved to think about the matter no further.

Then, a few days later, a serious-looking stranger was ushered into his office. The man was a private investigator and carried with him a series of documents and photographs that he wanted to show Alan. Bemused, Alan studied the material that lay before him. He was particularly intrigued by several photographs showing the inside of a helicopter packed with sophisticated electronic equipment in the place where the rear seats would usually be.

“What’s all this?” he asked the investigator.

“A jamming device,” the man replied. “It can be used to interfere with a network’s radio waves — all high-tech stuff.”

“I can see that, but why show me? What have I got to do with this?” Alan queried.

Before replying, the man walked across the floor and shut the door to the office. He returned to Alan’s desk and then, in a low, even tone said, “MTN hired that helicopter, stripped the insides and installed the jamming equipment before the trial with those journos began. Your network never had a chance; they completely messed it up.”

Alan was astonished. He knew that he and MTN were playing for high stakes, but this was ridiculous.

“How do you know it was MTN?’ Alan demanded, reluctant to think that this might be so.

The investigator handed Alan the proof of payment record for the hiring of the helicopter. He had also obtained the helicopter’s logbook that recorded the details of its flight path that day. It had traversed exactly the same route the car filled with journalists had taken through the streets of Johannesburg.

Alan was angry and disappointed to discover that MTN might have taken such unprincipled, not to mention illegal, action. But he did not believe for a moment that Bob would have allowed himself to get caught up in such deviousness. He would never have agreed to go along with such underhand tactics. Alan had to pay a seven-figure sum for the evidence, which he then took to Bob.

Bob was incredulous, just as Alan had expected him to be. On investigating the matter, Bob admitted that MTN had used a helicopter on the day of the trial, but assured Alan that the equipment on board had been used for monitoring the networks only, even though it had the capability of jamming a network.

But Alan was not going to let the issue go away quietly. If Bob was right, why had it been kept quiet from KPMG and the media? He presented his evidence to the press. He felt they had a duty to report the behind-the-scenes behaviour that had compromised the authenticity of their MTN versus Vodacom story.

He received apologies and it was clear that the affair had caused the press a great deal of embarrassment, but no major exposé of the affair was forthcoming. There was only one extensive story published by The Star on 28 July 1998, accompanied by an amusing black-spy versus white-spy cartoon. A senior director at KPMG also called Alan to apologise and to tell him that the company had withdrawn its “clean” audit. Alan had a further opportunity to reveal what had happened when Joan Joffe, Vodacom’s marketing manager at the time, told him that she was due to be interviewed on Radio 702 along with her MTN counterpart, Jacques Sellschop. The helicopter saga had left relations between the two network giants delicately poised, and Joan wanted Alan’s advice on how she should approach the interview.

“Give them hell,” he told her. And she did. Joan was not a street fighter, but she was not about to retreat into a corner. The interview was vicious. Sellschop denied all the allegations; Joan called him a scheming liar. She wasn’t comfortable with the interview, but she kept her poise. And the interview could not be judged a failure because of this, since the general consensus was that Vodacom had emerged as the moral victor. “The media played the story like a well-tuned fiddle,” says Joan. “We got so much mileage out of a situation that we hadn’t wanted to be part of in the first place.”

Still Alan was not satisfied. No-one was taking responsibility for the mess that had damaged Vodacom’s reputation. He decided to take MTN to court for defamation. He didn’t give a damn about the repercussions; MTN had to be held accountable for what it had done to his company.

Not long after, before court proceedings had begun, Alan received a call from then President Nelson Mandela inviting him for tea at the Union Buildings in Pretoria. Alan knew him well enough at this stage for the president to call him by his first name. He had first met Mandela in 1995 through a well-connected entrepreneur and mutual friend, Yusuf Surtee.

Alan thought at the time that the meeting with the president would be a case of shaking hands and leaving. However, when Alan arrived, Mandela graciously greeted him as if they had been friends for years. Alan was initially tongue-tied and hovered in awe. He remembered the afternoon he’d watched the old man leave Victor Verster prison on TV without an inkling of their meeting just five years later. From the minute Mandela shook his hand, he could have asked Alan anything and he would have gone to the ends of the Earth to do it for him — and he often did. Madiba, the clan name by which Mandela is affectionately known, built schools and clinics with private sector money because the government didn’t deliver as fast as he would have liked. Alan often used his shareholders’ money to fund these initiatives.

However, it was not a common occurrence that the president invited him for tea so he must have something important to discuss, thought Alan. Alan surmised that he wanted to discuss a potential project for Vodacom to take on. When he arrived, he bumped into Bob Chaphe in the foyer.

The two men were not on speaking terms and were clearly unhappy to be meeting under such circumstances.

“What are you doing here?” asked Alan, as politely as he could.

“I’ve been invited for tea,” replied Bob. “And you?”

“Same,” said Alan.

They exchanged puzzled glances. But before they had time to discuss the matter further, they were taken to see Madiba. After a minute or two of general conversation, Madiba outlined the reason why he had invited them.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I believe there is a court case pending between MTN and Vodacom. I am sure that you both have good reasons for the court case, but I don’t want to know what they are. However, it doesn’t look good for the country to have our top mobile network operators at loggerheads. There has to be another way. Why don’t you go into my private study and see if you can come up with a solution to all this. Come back and let me know what you decide.”

Alan and Bob left the room gulping like guppies. When they got to the study, neither knew what to say. They were both mortified to have been rapped over the knuckles. In utterly gracious terms, the president had told them to stop their petty squabbling, to remember their civic responsibilities, and to resolve their differences in a dignified, reasonable manner.

Neither wanted to disappoint Mandela, but since there was a court case pending, both were wondering how to go about resolving the matter in the absence of their lawyers. They sat in silence in the presidential study for a while, contemplating a way forward. They were offered drinks. Alan felt he needed a gin and tonic considering the situation, but settled for a glass of water instead.

Eventually Alan said, “I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to go back in there and tell the old man that we couldn’t come to an agreement.”

“Well, let’s get this sorted then,” Bob responded.

And so Alan withdrew the court action and all claims for damages. In return, Bob agreed to offer an apology to Vodacom, since he too was eager to put an end to any further damage to MTN’s already beleaguered reputation. In less than half an hour the matter was settled and Alan and Bob sought out the president.

Madiba smiled broadly, but before they could tell him that they had resolved the situation, he said, “I knew you wouldn’t disappoint me; thank you for sorting out your disagreement.”

Alan wondered how many other crises Mandela had solved by simply allowing his presence to be the catalyst for resolution. When Mandela asked you to do him a favour, Alan contemplated, you would rather disown your own mother than disappoint him.

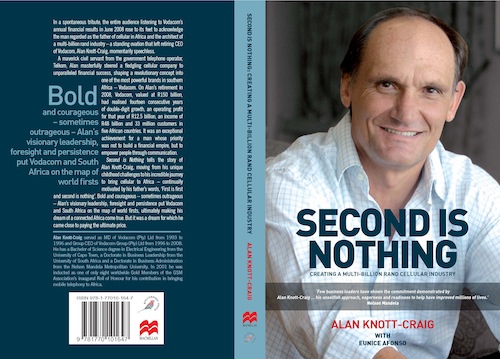

- Knott-Craig’s book, published by Pan Macmillan and Rollerbird Press, is on sale now for R185. This exclusive extract is published with the permission of the author

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter