Religion-fuelled conspiracy theories continue to pervade our culture.

Today, some claim energy drinks are Satanic plots. Others argue that shape-shifting reptiles secretly rule the world. And musicians from Kanye West to Katy Perry have been accused of conducting occult Illuminati rituals disguised as harmless stage performances.

But one of the strangest — and most persistent — conspiracy theories is the claim that the popular role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) is actually a recruiting tool for Satanism.

Last year, D&D celebrated its 40th anniversary, and the game’s publisher, Wizards of the Coast, has just announced a new transmedia storyline for the game called “Rage of Demons”.

Since many of these raging demons, such as Orcus, Baphomet and Demogorgon, are drawn from “actual” myths and legends, it’s a fitting time to explore the real fear that D&D is a crash course in evil occultism.

As a religion professor, I study the history and sociology of religious movements. While the opposition to D&D wasn’t always framed in religious terms, a particular strain of evangelical Christianity was the driving force behind the panic.

Why were these Christians so bothered by a game? And why did they claim the game was ungodly instead of merely unwholesome? Exploring these questions led me to conclude that fantasy role-playing games (RPGs) do, in fact, share traits in common with religious worldviews. Conversely, religious worldviews can resemble RPGs.

In 1974, Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax created Dungeons & Dragons, the first commercially viable fantasy role-playing game. Fantasy RPGs usually involve players assuming the role of characters in an imaginary world. Complicated rules (often involving multi-sided dice) are used to determine the outcome of a character’s actions. D&D quickly spread through college campuses and filtered down to secondary schools, where it was incorporated into programmes for gifted children.

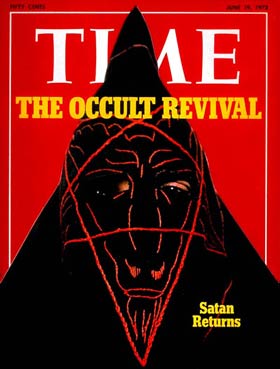

Beginning in the 1980s, rumours abounded that the game caused players to dissociate from reality and commit suicide. The decade also saw the apogee of “Satanic Panic”: when a coalition of evangelicals, talk show hosts and dubious “occult crime” experts claimed that Satanic cabals had infiltrated all aspects of society. According to psychiatrists like Lawrence Pazder, these groups conducted horrifying rituals in secret in order to corrupt innocent children and create brainwashed cultists.

Soon, church leaders, concerned parents, politicians and others began to claim that the Satanists had created D&D to indoctrinate children into the occult. They formed coalitions, petitioned federal agencies and worked to shut down school-based D&D clubs. Many of the self-proclaimed experts were invited to special police seminars on “occult crime”, where they claimed D&D led directly to involvement in criminal cults. They even drafted documents to help police interrogate adolescent players.

However, in many ways, RPGs and religious cultures aren’t so different: both involve a collective effort to construct and inhabit an alternative reality that is uniquely meaningful. Whereas gamers explore alternate realities using dice, character sheets and narrative, religious communities use sermons, hymns and rituals to create a sense of connection to another world.

The key difference is the frame through which this reality is understood. For role players, it’s purely fantasy. Religious cultures, on the other hand, generally regard otherworldly realities as real.

Watch: Satanic Panic: Christian broadcast network JCTV profiled a man who claimed to have been corrupted by Dungeons & Dragons:

Who led the charge?

One area in which this line of thinking can serve as an interpretive lens is the phenomenon of conspiracy theories.

In a 2000 interview, D& D creator Gary Gygax suggested that it is the claims-makers — rather than the gamers — whose grasp of reality is poor:

That a group playing a fantasy RPG will lose touch with reality or become “mind-controlled” is completely fatuous. This is obvious to any observer of or participant in RPG activity. Those who claim such an effect is possible are the ones who have lost touch with reality.

Indeed, when I traced the claims about the dangers of D&D back to their sources, I arrived at a handful of people who appear to have been either hopelessly uncritical, liars or mentally disturbed.

Figures who claimed D&D was a Satanic conspiracy included Patricia Pulling, founder of Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons (and author of The Devil’s Web: Who Is Stalking Your Children for Satan?), evangelist Mike Warnke, conspiracy theorist John Todd and author William Schnoebelen.

Warnke, Todd and Schnoebelen all claimed to have been powerful leaders of Satanic cults before converting to Christianity — claims that were eventually debunked in various Christian publications.

Cut from the same cloth

Interestingly, the Satanic conspiracies of the 1980s were constructed from many of the same elements as D&D — especially 1960s horror media. Some of D&D creator Dave Arneson’s early ideas for the game came from Creature Features — local TV programming featuring schlocky monster movies — and the vampire soap opera Dark Shadows.

But anti-D&D crusader Mike Warnke also confessed to loving Creature Features and other horror films as a child. Meanwhile, John Todd claimed to have been brought up in a family of witches named Collins who settled in the New England colonies — a plot line lifted from Dark Shadows.

As play worlds crafted from similar elements, Satanic conspiracy theories and D&D weirdly mirrored each other: both were replete with themes of fighting against demonic evil.

The difference, of course, is that while D&D is just a game, the conspiracy theorists refused to admit their play worlds were imaginary.

Play as inspiration and escape

Each of these figures described a parallel world in which they were opposed by Satanic forces. To them, their choices carried tremendous importance. But it doesn’t enhance our understanding to medicalise their behaviour or dismiss these figures as “insane”.

Generally, paranoid schizophrenics do not publish books, organise speaking tours at local churches or collaborate with like-minded people. Rather, the strange views of these conspiracy theorists seem to be the product of play not unlike an RPG. Their theories present an enchanted world in which they can assume heroic roles.

Play is a serious thing. It creates a situation in which real-world elements may be removed from their established order, reassessed and repurposed. A child at play can take a banana and imagine it is a phone, a pistol or a yellow rocket ship. In play, we have the power to reimagine the world.

Theorists such as Johan Huizinga — and, more recently, Robert Bellah — have argued that all human culture, including religion, was derived from play.

Bellah even called play “the first alternative reality” from which the frames of science, philosophy and religion are ultimately derived.

In a sense, conspiracy theories are a form of “corrupted play”, in which the frame of play is lost and the game passes for reality.

One factor contributing to this corruption of play may be the emphasis on Biblical inerrancy — the idea that Bible stories are “true” in the same sense that historical and scientific claims are “true”.

This frame of religious thinking accompanied the rise of Fundamentalism in the early 20th century.

And with this move comes a suspicion of discrete frames of meaning. Several of the anti-D&D crusaders claimed that when players “imagine” a demon, they are actually having a metaphysical encounter with a real demon. Others claimed that the imagination itself is an unbiblical and heretical faculty.

Because imagination and reality were confounded together, people from these religious cultures had no alternative reality onto which to project their natural, heroic fantasies. They could battle evil only if that evil was given a literal existence in the form of demonic paranoia and conspiracy theories.

In this sense, the impulse to spin conspiracy theories is a kind of spiritual malaise that arises from a sense of disenchantment, combined with a fear of the imagination.

The irony is that the conspiracy theorists who claimed D&D was Satanic were the ones who could have benefited the most from playing it.![]()

- Joseph P Laycock is assistant professor of religious Studies at Texas State University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation