It may sound far-fetched at first, but there’s a growing fear of the damage a newly aggressive Russia might inflict in a time of tension or conflict simply by damaging or cutting the undersea cables that carry almost all of the West’s Internet traffic.

The New York Times reported that Russian submarines and spy ships were aggressively operating near the vital undersea cables. Could they be preparing for a new form of warfare?

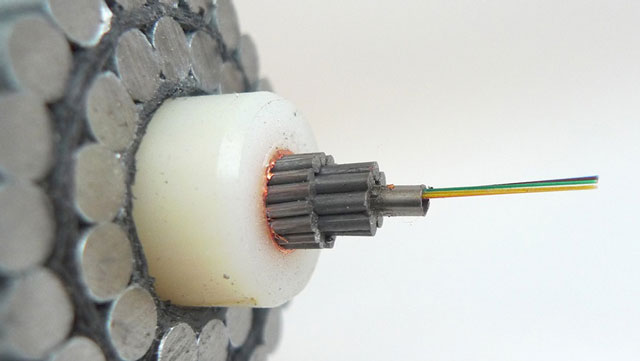

The perfect global cyberattack could involve severing the fibre-optic cables at some of their hardest-to-access locations in order to halt the instant communications on which the West’s governments, military, economies and citizens have grown dependent.

Effectively, this would cripple world commerce and communications, destabilise government business and introduce uncertainty into military operations. A significant volume of military data is routed via the Internet backbone.

The fibre-optic cables that carry the majority of the planet’s Internet traffic follow designated paths under the oceans. To cause global chaos, all that is needed is some “wire cutters” (realistically a submarine with a depth charge would do). This is not rocket science and there will be no need for clever hackers.

While there is no evidence yet of any “cable snipping”, there is concern among senior US and allied military and intelligence officials over the accelerated activity by Russian armed forces around the globe. At the same time, the internal debate in Washington illustrates how the US is viewing Russian moves with distrust. Surveillance activity shows a significant increase in Russian activity along the known routes of the cables and more than a dozen officials confirmed in broad terms that it had become the source of significant attention in the Pentagon.

Talking to the BBC’s Gordon Corera, the deputy director of the US National Security Agency, Richard Ledgett, warned of the increasing danger of destructive cyberattacks by nation states in addition to criminal organisations. A concerted cyberattack against another nation state can result in the breaking down of society and the loss in ability to defend itself. Information warfare (IW) is an extension of electronic warfare, but importantly it embraces cyberwarfare.

More than 50% of effort in future conflicts will be in both cyberspace and electromagnetically in the ether — this will be known as “information warfare”. It will disrupt radio communications, radar and intelligence surveillance, military command and control, weapon systems control, aircraft navigation, national infrastructures, emergency services, and all Internet communication. Severing Internet backbone networks will cause major worldwide disruption causing widespread suffering without firing a single shot in anger.

In March 2003, allied forces led by the US began Operation Iraqi Freedom. In the first few days of that conflict, an information war took place that completely neutralised the ability of Iraq to use the electromagnetic spectrum and the Internet. Its armed forces and its civilian infrastructure was virtually paralysed. The conflict lasted just 43 days and Iraq had a formidable and well-equipped military.

Russia has long realised that this “soft” warfare is the equal partner to the familiar hard-weapons side and is planning to spend billions perfecting techniques required. Cyberwarfare has become an important weapon in the military arsenal.

Attack on Estonia

In April 2007, denial-of-service (DOS) attacks targeted Estonian websites including the Estonian parliament, banks, ministries, newspapers and broadcasters, amid the country’s disagreement with Russia on the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn (a Soviet war grave monument) together with Soviet war graves in Tallinn.

Cyber analysts concluded that the cyberattack on Estonia was well planned and sophisticated, with no precedent. Although Russia vehemently denied involvement the foundations for future IW were becoming established. Military strategists worldwide study the attack to for its inclusion into an order of battle, and to develop mitigating measures.

Military and government strategists did not have to wait long for another example of IW. On 20 July 2008, just prior to the Russian military invasion of Georgia to support the self-proclaimed republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, a massive Russian-based Internet DOS attack against Georgia began. Targets for the distributed DOS attack included websites of the Georgian president, Mikheil Saakashvili, the OSInform news agency and OS radio station. It was also reported that key sections of Georgia’s Internet traffic had been rerouted through servers based in Russia and Turkey, where the traffic was either blocked or diverted — effectively closing the Internet in Georgia for the duration of hostilities.

There was also circumstantial evidence that the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline control system was targeted by a sophisticated computer virus similar to Stuxnet, which led to an uncontrolled pressure incident. The Russian government again distanced itself from any involvement and blamed the Russian criminal fraternity. However, observers have acknowledged that the resources needed for this level of attack point to a nation-state involvement.

The escalating military conflict in Ukraine has featured a mirrored cyberwar between the two sides with distributed DOS and malware attacks against public websites, banks, radio and television channels and public utilities. At the same time, Ukrainian forces have grappled with formidable Russian electronic warfare capabilities.

Russia has deployed its new multi-functional Krasukha-4 electronic warfare systems to support Ukrainian separatists and “volunteer” Russian combat troops. It is the Krasukha-4 that has been deployed to Syria. Russia has again denied any involvement in the cyberattack and blames criminal organisations. But this is the first time a fully integrated IW has been witnessed.

Lieutenant-General Ben Hodges, the commander of the US army in Europe, has described the Russian capability as “eye watering” and confirmed that US army personnel from Nato are working alongside their counterparts in the Ukrainian army to gain first-hand experience of information warfare from a state-based adversary.

Is Russia is developing the capability to repeat Operation Iraqi Freedom on a global scale? If its investment in IW is any measure, we should be concerned — this investment is not being matched by the US and Europe combined.

Western leaders should be made aware of the need to accelerate development of IW capability and train more people to deal with it. They should stop isolating Russia in the world and putting it in a position where it feels the need to cash in on this investment.![]()

- David Stupples is professor of electrical and electronic engineering and director of electronic warfare at City University London

- This article was originally published on The Conversation