South Africa has yet again sided with repressive regimes such as Russia, China and Saudi Arabia against progressive efforts by the United Nations. This is counter to the spirit of the country’s enlightened constitution.

This month, the UN voted on a resolution for the “promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet”. This was in response to a UN Special Rapporteur report on the promotion of freedom of expression online.

The rapporteur examined various threats to free expression online, including the use of technological surveillance and the excessive use of defamation laws.

About 70 countries signed the resolution. They included Australia, Brazil, Haiti, Mexico, Nigeria, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey and the US. South Africa was one of 15 states that voted against it. Others in this camp included Russia, China, India, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Venezuela, Cuba and the United Arab Emirates.

Since the advent of democracy in South Africa and the country’s adoption of a globally celebrated constitution, its votes on human rights have been of particular significance, especially in the developing world. That the government would vote against rights enshrined in its own constitution — rights that were strenuously fought for — reflects a troubling cynicism and indifference to its human rights commitments.

The resolution is designed to safeguard access to the Internet as an important human right. It exhorts countries to provide and expand access to the Internet. It also urges them not to disable Internet access, even for political and security reasons.

The report recognises the vital role the Internet plays in supporting the right to education. As such, it stresses the “need to address digital literacy and the digital divide” between and within countries. Specifically, it notes that enhancing access to the Internet for women and girls will help reduce gender disparities.

The resolution encompassed several goals. These include:

- Protecting the same rights online that people have offline, especially freedom of expression and privacy;

- Recognising the Internet as “a driving force in accelerating progress”, including economic development;

- Preventing government harassment, including torture and imprisonment, for those who post controversial political opinions online;

- Requesting governments to investigate extrajudicial killings, attacks, intimidation, gender-based violence and other forms of abuse against those who post controversial material online;

- Condemning government measures that intentionally prevent or disrupt access to, or dissemination of, information online; and

- Requesting governments to address Internet security concerns in line with their international human rights obligations.

South Africa’s objections

South Africa’s reluctance to support the resolution was based on a few factors, including that:

- South Africans are already guaranteed the right to freedom of opinion and expression in the constitution;

- The exercise of this right is not absolute, specifically in a context in which South Africa is trying to overcome a flood of racist hate speech on the Internet; and

- The resolution fails to adequately address acts of hatred on the Internet, including cyber bullying.

There are, of course, legitimate reasons for limiting freedom of expression.

These speak to South Africa’s traumatic history of apartheid and its legacies.

In an attempt to address these problems, the country has, for example, passed legislation against hate speech. Its Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Discrimination Act specifically prohibits hate speech. Other laws with a bearing on free speech include those against child pornography or defamation.

Such restrictions are not unusual. Even the US, the bastion of the right to freedom of expression, limits the right in the face of “fighting words” that may lead to violence.

The question is whether there should be any limitations on the right to freedom of expression online. If so, what considerations ought to be employed?

In other words, in balancing competing rights, which rights should prevail?

Current events in South Africa highlight the difficulty of balancing the right of freedom of expression with other rights. Examples include the much publicised case of former KwaZulu-Natal realtor Penny Sparrow, who described black beach goers as monkeys on Facebook. Another involves Cape Town attorney Matthew Theunissen. He posted racist views in response to a decision by the sports minister to ban certain sports from hosting major events due to their lack of racial transformation.

In such cases, there is a need to balance people’s rights to equality, dignity and not to be subjected to racist hate speech against other people’s right to freedom of expression. In racially bruised South Africa, the former rights outweigh the latter.

Similarly, legitimate security concerns might pressure governments to curb certain kinds of Internet speech if they threaten public safety. And the rights of children and their need for protection provide legitimate reasons for outlawing child pornography.

Where South Africa got it wrong

South Africa erred in voting against the resolution because its concerns are actually addressed by the resolution.

The resolution takes cognisance of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. These provide for the consideration of other rights in promoting the right to freedom of expression.

Significantly, South Africa’s constitution provides that free speech is not protected when it advocates hatred based on race, ethnicity, gender and religion. These limitations adequately address the government’s fears in relation to the UN resolution.

What is most disappointing about the South African response is the message it sends about its attitude to its human rights obligations. It also reflects negatively on the country’s standing as being committed to human rights.

South Africans should be concerned with the illiberal positions the government has taken at the UN over the past few years. These include its recent abstention from voting on the appointment of a UN Rapporteur for the protection of sexual minorities. Such actions diminish the aspirations espoused in the country’s bill of rights. South Africans deserve better.![]()

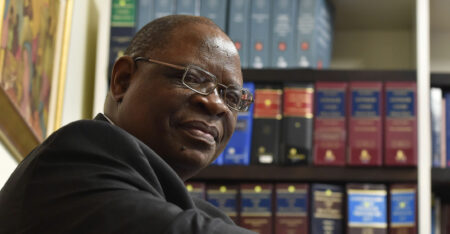

- Penelope Andrews is dean of law and professor, University of Cape Town

- This article was originally published on The Conversation