[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a conference call last October, Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos described the hip-hop drama The Get Down as a success, like the booming streaming service’s other popular shows.

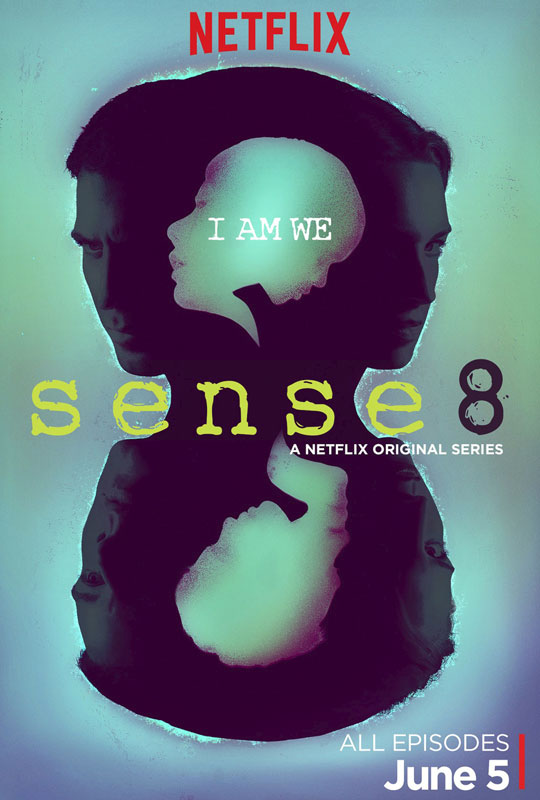

Eight months and 11 episodes later, The Get Down is history, a flop after one season on the world’s largest paid video service. The sci-fi thriller Sense8, another of the company’s lavish productions, was scrapped after two seasons.

The back-to-back cancellations caught Hollywood by surprise. Netflix has defied convention by offering no inkling of how many people watch its shows and claiming just about everything is a hit. That’s vexed competitors worried about Netflix’s growing customer base and influence in Hollywood. The streaming company will spend more than US$6bn on programming this year, a good chunk of that on about a thousand hours of original shows.

“It’s a competitive advantage,” said Anthony DiClemente, an Instinet analyst. “They know more about who and how many people are watching than content creators know.”

Cancellations are common for all TV networks — even for Netflix, which has wrapped up most of its first crop of original shows. Without the need to attract advertisers, the company is shielded from the weekly audience ratings that determine the fate of most dramas and sitcoms. While an estimated 18m people in the US watch CBS’s NCIS on Tuesday nights, no one knows how many see Netflix’s House of Cards — especially the Hollywood insiders vying for a chunk of the company’s $6bn yearly programming budget.

“One of the great things about Netflix is we don’t have to release ratings,” CEO Reed Hastings said in an interview this week on CNBC. “Each show gets to have its own audience because it is very personalised.”

That’s great for Netflix and its 100m customers, who pay up to $12/month for the service. Without pressure to deliver weekly ratings, the company can give shows time to develop a following. House of Cards, the thriller starring Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, just started its fifth season.

In the dark

It’s not so great for competitors — or producers who must grope for ways to measure the success of a given programme and wonder if they’re getting paid enough by the streaming service. With no data, they must rely on the positive remarks Netflix executives make for all their shows.

John Landgraf, CEO of 21st Century Fox’s cable network FX, has routinely criticised the lack of verifiable viewer data from his competitor.

Analysts estimate the Los Gatos, California-based company spends more than $1bn/year on original shows, with the rest going toward reruns and older films from others. To be fair, Netflix has had other flops, including some it has acknowledged, like the sequel to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. A couple cancellations late last year also show Netflix is as fallible as anyone.

And the online network isn’t the only player that doesn’t have to worry about ratings. Time Warner’s HBO, like Netflix, relies on subscribers to finance its programming and earned $2bn last year. Amazon.com has also emerged as a force in streaming, spending about $4,5bn annually on movies and TV shows, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co estimates, including award winners like Manchester by the Sea and Transparent.

Some of Netflix’s recent cancellations were expensive. The Get Down cost at least $120m for one season, according to Variety, while the first season of Marco Polo, which was cancelled last year, cost $90m, The New York Times said.

Even when Netflix throws in the towel, as it did with Sense8 after 23 episodes, the company professes success: “It is everything we and the fans dreamed it would be: bold, emotional, stunning, kick-ass and outright unforgettable,” Cindy Holland, vice president of original content, said on the Netflix website.

Netflix has said in the past cancellations occur when shows don’t attract enough viewers to justify their costs. On TV this week, Hastings said Netflix needs to pull the plug more often. If it doesn’t, it isn’t taking any risks.

Netflix has vowed to deliver material profit in 2017 after years of operating near break even, and earnings did reach a new high in the first quarter. Yet cash flow continues to be negative and the company is still borrowing money to fund production.

That suggests the company will be quicker to end shows that aren’t working.

“It’s grown-up to admit failure; it highlights to people on the creative side and Wall Street that it doesn’t work,” said Laura Martin, an analyst with Needham & Co who was recommending the stock until April. “If it’s not working, they should save the money and put it into something that might work.” — Reported by Lucas Shaw, (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP