“He awoke — and wanted Mars.”

That’s the first line of Philip K Dick’s classic novella, We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, the inspiration for the Total Recall films. I first came across the story in a sci-fi anthology back in high school, and I can remember the force of the yearning the words roused in me: I wanted Mars, too. After all, men had just walked on the moon and everybody knew Mars would be next.

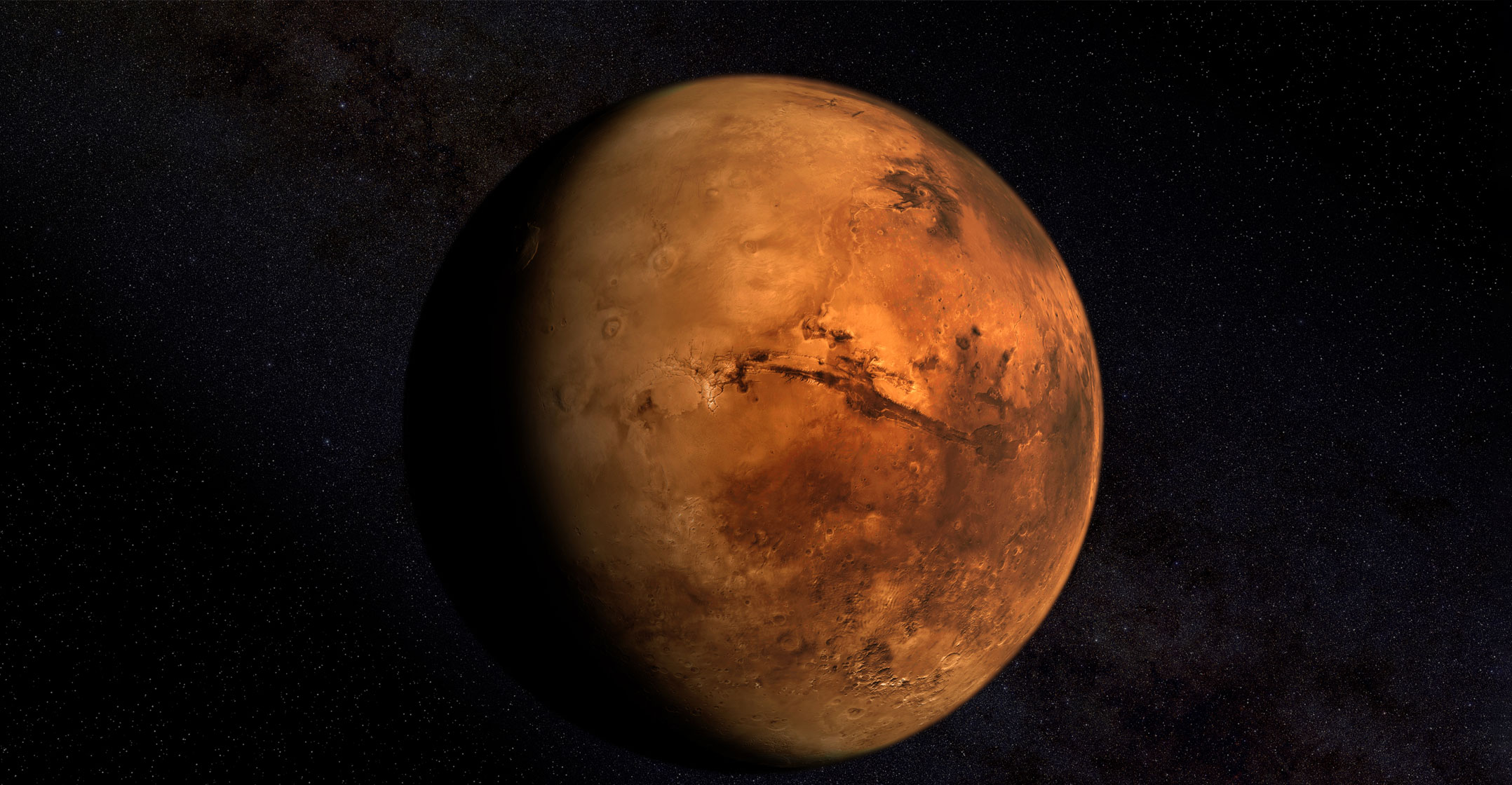

Well, the moon landing will be celebrating its 50th anniversary in two years, and human beings haven’t even tried to walk anywhere else. So when Elon Musk announced on Friday that he hopes to send a manned mission to the red planet by 2022 — just five years from now — I felt my heart leap.

The 1969 moon landing capped an era of enormous optimism about what humanity could achieve. Norman Borlaug was saving hundreds of millions from starvation. Integrated circuits heralded a digital revolution. The campy innocence of the original Star Trek dates from those years. So do the Jetsons. People actually believed that science was the endless frontier.

Since then our species has turned its vision inward; our image of human possibility has grown cramped and pessimistic. We dream less of reaching the stars than of winning the next election; less of maturing as a species than of shunning those who are different; less of the blessings of an advanced technological tomorrow than of an apocalyptic future marked by a desperate struggle to survive. Maybe a focus on the possibility of reaching our nearest planetary neighbor will help change all that.

Mars has long fascinated us. The ancients associated it with various gods. Venus shines brighter in the sky, but somehow we have always known that our destiny lies with Mars. Filmmakers have been taking us there for decades. The planet has intrigued novelists for well over 100 years. Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles may be dated in its science, but as social commentary on the 1940s, it stands unrivalled in the sci-fi canon. In 1893, the astronomer Camille Flammarion penned Omega: the Last Days of the World, a novel by turns hilarious and sobering. Martian astronomers contact humanity out of the blue to warn of a comet soon to strike Earth. The message divides Earth’s scientists, political leaders, journalists and theologians, who argue over whether the message is a hoax, and what to do if it’s authentic. Then the comet strikes, disaster follows — and we cut to what the world is like centuries later. (For one thing, the survivors develop new senses; for another, the lower classes overthrow the elites. Hollywood, take notice.)

Musk first?

That’s all fiction. But maybe we’ll get there in reality. Nasa has been pushing the idea for years. The agency’s current timeline would put humans on the planet in the 2030s. China intends to get there first. Musk claims he can beat them both.

Every time someone proposes a mission to Mars, critics worry that the whole thing will be too expensive, that the money could be better spent elsewhere. Although I get their point, they’re only half right: the same complaint could easily be directed at every dollar we spend on rent or education or food. Besides, in Musk’s scheme the investment would come (mostly) from private sources. The point is to make the project self-sustaining.

For those of us who dream of the stars, reaching Mars has always been a preliminary step. Musk agrees. His bolder plan is for humanity to advance along the path of becoming “a space-bearing civilisation and a multi-planetary species” — an ambition he laid out earlier this year in a thoughtful paper. Musk argues that what he calls the “Apollo-style approach” would make the cost of colonising Mars prohibitive, something on the order of US$10bn a person in current dollars. But people would move in droves, he insists, if the cost can be brought down to somewhere near the median price of a US home, around $200 000. Most of Musk’s paper is devoted to laying out a theory on how, over time, we might bring down the cost. For instance, he proposes establishing propellant depots throughout the solar system, potentially as far away as Pluto. The most important factor, however, is the development of multiple-use vehicles — the advance that made commercial air travel cost-effective.

With frequent flights, you can take an aircraft that costs $90m and buy a ticket on Southwest right now from Los Angeles to Vegas for $43, including taxes. If it were single use, it would cost $500 000 per flight.

The booster rocket that he describes in the paper is enormous. Musk has since decided that his original vision was impractical. He now wants to build a much smaller version that will carry perhaps 100 people at a time. He posted a series of images on Instagram to show both the vehicle he envisions and the Mars colony he imagines it would help populate.

It’s a lovely and elegant idea. Can we do it? I have no idea. But Musk’s confidence rekindles in me the old excitement. Perhaps we need not be earthbound forever. Perhaps we as a species can once more look skyward with a shared sense of anticipation and excitement, confident that if we cannot reach the stars, our children will. So I hope we’ll try. I may not see Mars in my lifetime, but I’m thrilled that you might see it in yours. — Written by Stephen L Carter, (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP

- Stephen L Carter is professor of law at Yale University and was a clerk to US supreme court justice Thurgood Marshall. His novels include The Emperor of Ocean Park and Back Channel, and his nonfiction includes Civility and Integrity