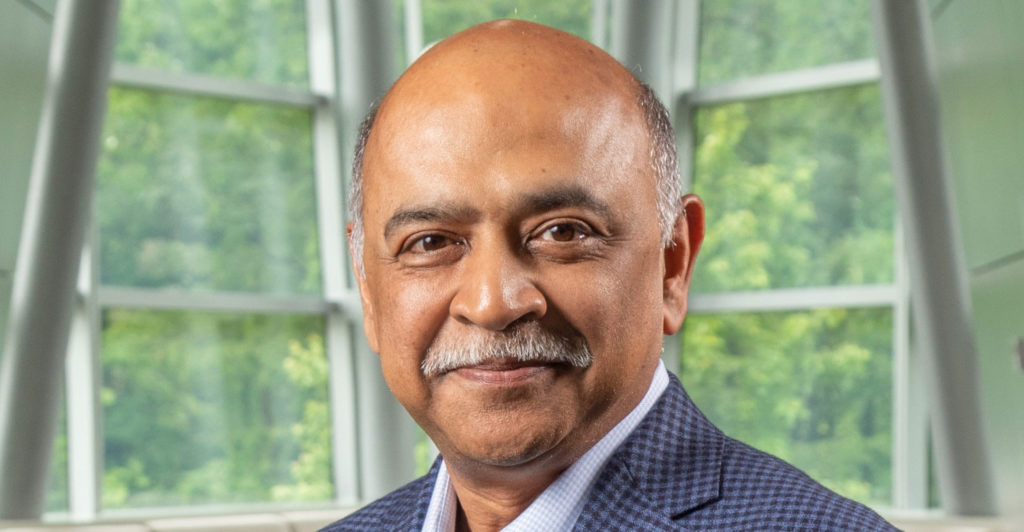

In July 2017, IBM executive Arvind Krishna walked into a routine meeting with senior leaders and delivered a surprise pitch that changed the course of the iconic 108-year-old company’s future.

For months Krishna, the head of IBM’s cloud computing division, had been thinking about a way to connect clients’ most important data, which was often held on private servers, to public cloud servers run by others including IBM, Amazon.com and Microsoft. Finally he proposed a way, creating IBM’s so-called hybrid multi-cloud strategy.

The company was coming off 19 consecutive quarters of shrinking revenue and lagging far behind rivals in cloud computing, the lucrative new field in business technology, when Krishna stood in front of a crowd of executives, including CEO Ginni Rometty, at the company’s Armonk, New York headquarters. He ran a live demonstration of some of the hybrid cloud products from his Mac laptop.

“I showed an early version, not yet complete, of what we could do to about 60 or 70 senior leaders from inside IBM,” Krishna said in an interview last year. “I think the light bulb went off for everybody.” The first question he received from the group was: when will it be ready to go to market?

IBM launched its hybrid cloud product three months later. Rometty called it a “game changer” for the company. Last year, at Krishna’s suggestion, IBM acquired open-source software provider Red Hat for US$34-billion to further that vision — a strategy some Wall Street pundits believe will finally breathe life back into Big Blue.

On Thursday, IBM announced that Rometty would be stepping down after almost 40 years at the company and Krishna would be taking over. Though generally respected by her peers, Rometty, 62, inherited many challenges that she was ultimately unable to overcome. During her tenure, revenue and IBM’s valuation shrank by 25%, in opposition to other tech companies and the broader market, which have seen spectacular gains. Rometty, who will step down as CEO effective 6 April, will stay on as executive chairman to the end of the year.

Radical transformation

Restoring IBM even part way back to its glory days will require a radical transformation, steering the company away from its slow-growing unprofitable legacy businesses and toward the future of modern computing. Analysts say Krishna is up for the task.

Krishna, 57, has spent his entire career at IBM and witnessed the company’s ups and downs as it went from the world leader in computing and IT services to missing the cloud revolution and falling behind nimbler, younger rivals like Amazon.

Krishna’s elevation is reminiscent of the appointment of Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s cloud chief, into the CEO role in 2014. Like Krishna, Nadella also bet big on the cloud and won, boosting Microsoft’s market valuation to more than $1-trillion. IBM shares gained 4.5% on Friday after the announcement of the leadership change, valuing the company at about $126-billion.

As the new CEO of IBM, Krishna would be a “Nadella-like” leader — calm but deep, firm but unaggressive, said Rishikesha Krishnan, a professor of strategy at the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore. “If a company intends to make a serious shift or change, he’d be the man.”

Krishnan studied with Krishna at India’s premier engineering school, the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur. “IQ levels on the campus are high, but even then he stood out as smart and articulate,” Krishnan said.

Soft-spoken, relaxed and accessible, Krishna represents a new leadership style for IBM, which has an entrenched culture of bureaucracy and formalities. On a recent trip to India, he spent hours in the IBM cafeteria chatting to whomever approached him, according to a person who observed the interaction but didn’t want to be named describing a private event. He socialised with team members until the early hours of the morning, answering questions and offering market insights.

Krishna joined IBM in 1990 after studying in Kanpur and obtaining a PhD in electrical engineering from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. With vast industry knowledge and a tendency to speak at a rapid pace, Krishna can be hard to keep up with but is known for a willingness to simplify complex terms.

In an interview last February, Krishna was asked to describe hybrid-cloud computing in two sentences. He gave a thorough and speedy analysis of the intersection between public cloud, private cloud, data centres, applications, existing infrastructure and other technical terms. At the end of his answer, Krishna said: “Now that wasn’t quite two sentences, but it was no more than two minutes.” He then laughed, adding: “Was that all intelligible?”

IBM’s hybrid cloud strategy was “a long time coming”, Krishna said. “Maybe we should have done it a year or two earlier, but then there’s this question of would the world be ready? I think if we’d done it in 2015 it might’ve been too early.”

Not fast enough

Others disagree, saying one of the main criticisms against Rometty was not launching IBM’s transition soon enough. IBM has a lot of catching up to do in the trillion-dollar cloud market where Amazon and Microsoft are far out in front, followed by Google. They are all developing similar software in the hybrid-cloud market, too. While IBM gained ground with the Red Hat purchase, the fierce competition with such formidable rivals won’t leave much room for error.

Former longtime IBM employee and historian James Cortada, a senior research fellow at the University of Minnesota, said hybrid cloud represents the company’s third radical transformation in its history. In the 1950s, IBM moved from tabulating equipment to computers; in the 1990s, it shifted to software and services; and now hybrid is the future. “Rometty initiated that next fundamental transition or transformation for the company, but that went too slowly for a lot of people,” Cortada said.

Krishna will also benefit from a strong partner in Jim Whitehurst, the 52-year-old CEO of Red Hat who was elevated to IBM president, the first time the company has given an executive that title on its own.

Krishna will also benefit from a strong partner in Jim Whitehurst, the 52-year-old CEO of Red Hat who was elevated to IBM president, the first time the company has given an executive that title on its own.

Whitehurst has been running a smaller but much faster growing company at the cutting edge of cloud migration, said Stifel Nicolaus & Co analyst David Grossman. The combination of the two of them sets up a “very interesting and complimentary team”.

Together, Krishna and Whitehurst bring software to the core of the company.

“Now the two top dogs running IBM are cloud purists,” said Steve Duplessie, founder of Enterprise Strategy Group. “The old IBM died a while ago and they had to change. This lets them remake themselves before it’s too late.” — Reported by Olivia Carville, with assistance from Saritha Rai, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP