From Seattle to Silicon Valley to Austin, a grim new reality is setting in across the US tech landscape: a heady, decades-long era of rapid sales gains, boundless jobs growth and ever-soaring share prices is coming to an end.

From Seattle to Silicon Valley to Austin, a grim new reality is setting in across the US tech landscape: a heady, decades-long era of rapid sales gains, boundless jobs growth and ever-soaring share prices is coming to an end.

What’s emerging in its place is an age of diminished expectations marked by job cuts and hiring slowdowns, slashed growth projections, and shelved expansion plans. The malaise is damaging employee morale, affecting the industry’s ability to attract talent, and has wide-ranging implications for US economic growth and innovation.

Illustrations of a dour new business climate surface daily against the backdrop of a prolonged economic slowdown, a grinding war in Europe, rising interest rates and inflation, and a global pandemic dragging into its third year. In the past two weeks, a parade of big names joined the crowd. Social media app Snap on 23 May pruned sales and profit forecasts and said it would slow hiring. The next day, Lyft said it would bring on fewer people and look for other cost cuts. Days later, Microsoft tapped the brakes on hiring in several key divisions, and Instacart said it would dial back hiring plans to nip costs ahead of a planned listing.

The drumbeat continued last week, as Tesla CEO Elon Musk told employees the electric vehicle maker needed to reduce its salaried workforce by 10% and pause hiring worldwide. Cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase Global also said it would extend a hiring freeze and rescind a number of accepted job offers, citing market conditions.

Similarly gloomy pronouncements had already been dribbling out for weeks. Amazon.com has too many workers and too much warehouse space, and its business is hurting from rapidly rising inflation costs. Facebook parent Meta Platforms is easing hiring and paring expenses, and Twitter instituted a hiring freeze and withdrew some job offers ahead of a planned takeover by Musk. Apple warned in April that restrictions related to Covid-19 lockdowns in China would shave as much as US$8-billion from revenue in the current quarter.

The humbled corporate ambitions signify a vibe shift for an industry that had seemed invulnerable, once offering workers and investors protection from the instability of the larger economy.

‘Fundamental things’

“They are no longer sure bets,” said Tom Forte, a tech analyst at D.A. Davidson, of the technology industry’s behemoths. “They aren’t sure bets because there are a number of fundamental things working against them.”

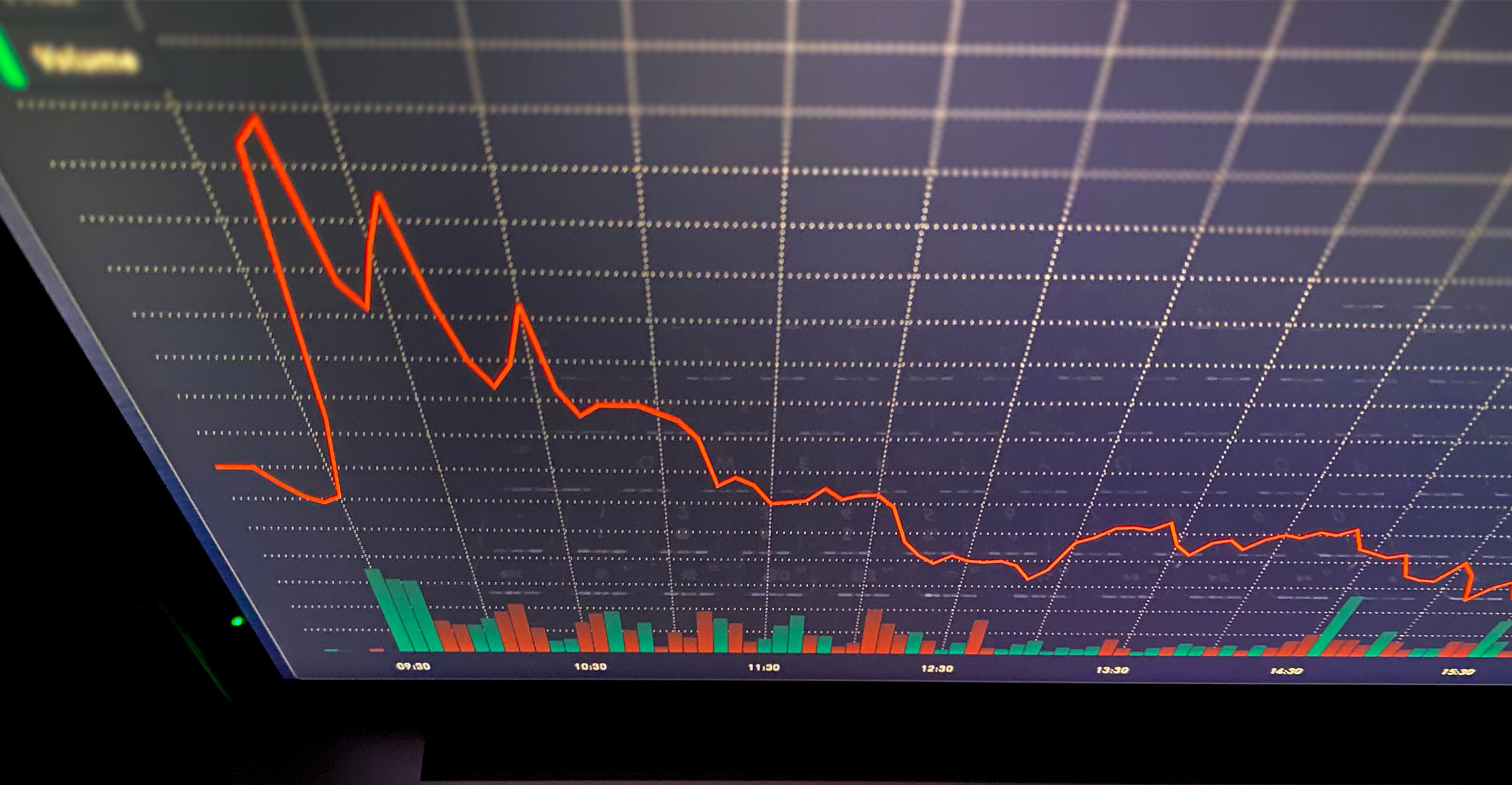

The Nasdaq Composite Index has lost a quarter of its value since 19 November, when it reached an all-time high. That’s even taking into account the index’s 5.8% rebound in the past two weeks.

The spectre of job cuts has begun to haunt the Silicon Valley psyche. On Blind, an app that employees can use to talk anonymously about their employers, discussions about hiring freezes increased by 13 times from 19 April to 19 May compared to a year earlier. Layoff discussions increased by five times, and talk about a recession is up by 50 times. Unfounded speculation that Meta was gearing up for a round of firings ripped through social media in May, resulting in the creation of the hashtag #metalayoff, which began trending on LinkedIn. Dozens of recruiters and employers began using the hashtag to offer alternative job openings. A Meta spokesman said the company has no current plans for staff reductions.

Still, what was once an engine of growth for the US economy has sputtered of late. More than 126 000 tech workers have lost their jobs since the beginning of the pandemic, according to Layoffs.fyi. Netflix said last month it’s laying off about 150 workers after reporting an unexpected subscriber loss; the streaming giant’s shares have tumbled 71% since mid-November. At Meta, managers are slowing hiring for many mid-to-senior-level positions companywide, and in April cut back on adding engineers with limited experience.

Twitter employees, meanwhile, are bracing for potential layoffs as the company awaits the arrival of new owner Musk, whose pitch to bankers included cost cuts. CEO Parag Agrawal jumped ahead in early May, sending Twitter’s 7 500-plus employees a note explaining the social network would start with reductions in travel, marketing and event costs, with leaders told to “manage tightly to your budgets, prioritising what matters most”.

Likewise, Uber’s Dara Khosrowshahi said in a memo to staff that the ride-hailing giant would “treat hiring as a privilege and be deliberate about when and where we add headcount”. The sentiment is taking a toll on morale internally, said an Uber employee who asked not to be identified.

The shock is probably the biggest at companies like Meta, Twitter and Uber, which were still in relative infancy the last time the tech industry was hit, during the financial crisis in 2008. Things were worse still when the dot-com bubble burst at the turn of the century. The difference this time is that the pandemic reinforced how important and necessary many of these tech products are, giving them some cushion against the initial economic ravages of the Covid-19 shutdowns.

“Everybody discovered that tech was not only nice, it was indispensable,” said Russell Hancock, CEO of Joint Venture Silicon Valley, a nonprofit that studies Silicon Valley and its economy. What’s happening now appears to be a market correction, Hancock added, though he also worries that some of the shine and innovation of the tech industry is going away as products like streaming services and social networking become more of a utility.

The aura of invincibility might be wearing off, but Silicon Valley is far from dead. Unemployment in the California region is just 2%

It’s possible “we’ll start to think about [tech] sort of like the gas lines going into our homes, or electricity”, he said. “That’s kind of a new thing for Silicon Valley. It’s sort of a Detroit kind of existence where cars just became the backdrop, the furniture of the region.”

With the companies preparing for a long season of uncertainty about their businesses, they’re having to make hard choices about investments beyond hiring and marketing. Amazon.com, which in 2020 invested heavily in the staffing and warehouse space it needed to meet a pandemic-related surge in delivery demand, now finds itself with too many warehouses and too many workers.

The Seattle-based company’s announcement that it has more space than it needs spooked hundreds of employees in its real-estate division, according to a person familiar with the situation. Employees who previously juggled multiple construction projects suddenly have little to do, and have been advised by their managers to use extra time to focus on “learning and development”, which hasn’t been reassuring, the person said.

Scaling back

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, said in February that the company was prioritising some product efforts like its TikTok competitor Reels, private messaging and the metaverse. “We’re shifting the bulk of the energy inside the company towards those high-priority areas,” Zuckerberg said in April. The company said it was scaling back expenses by $3-billion for 2022, the first signal that it’s becoming more judicious with its investments.

The aura of invincibility might be wearing off, but Silicon Valley is far from dead. Unemployment in the California region is just 2% — the lowest it’s been since 1999, according to Joint Venture. Additional data from the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy found Bay Area job growth over the past year of 5.8%, brisker than the national and state averages.

Any slowdown in hiring needs to be framed within the context of tech’s meteoric rise, says Stephen Levy, director and senior economist at CCSCE. “Does the world want more of the goods and services that tech produces, and is that a growth sector over time?” Levy said. “The answer is yes.” — (c) 2022 Bloomberg LP