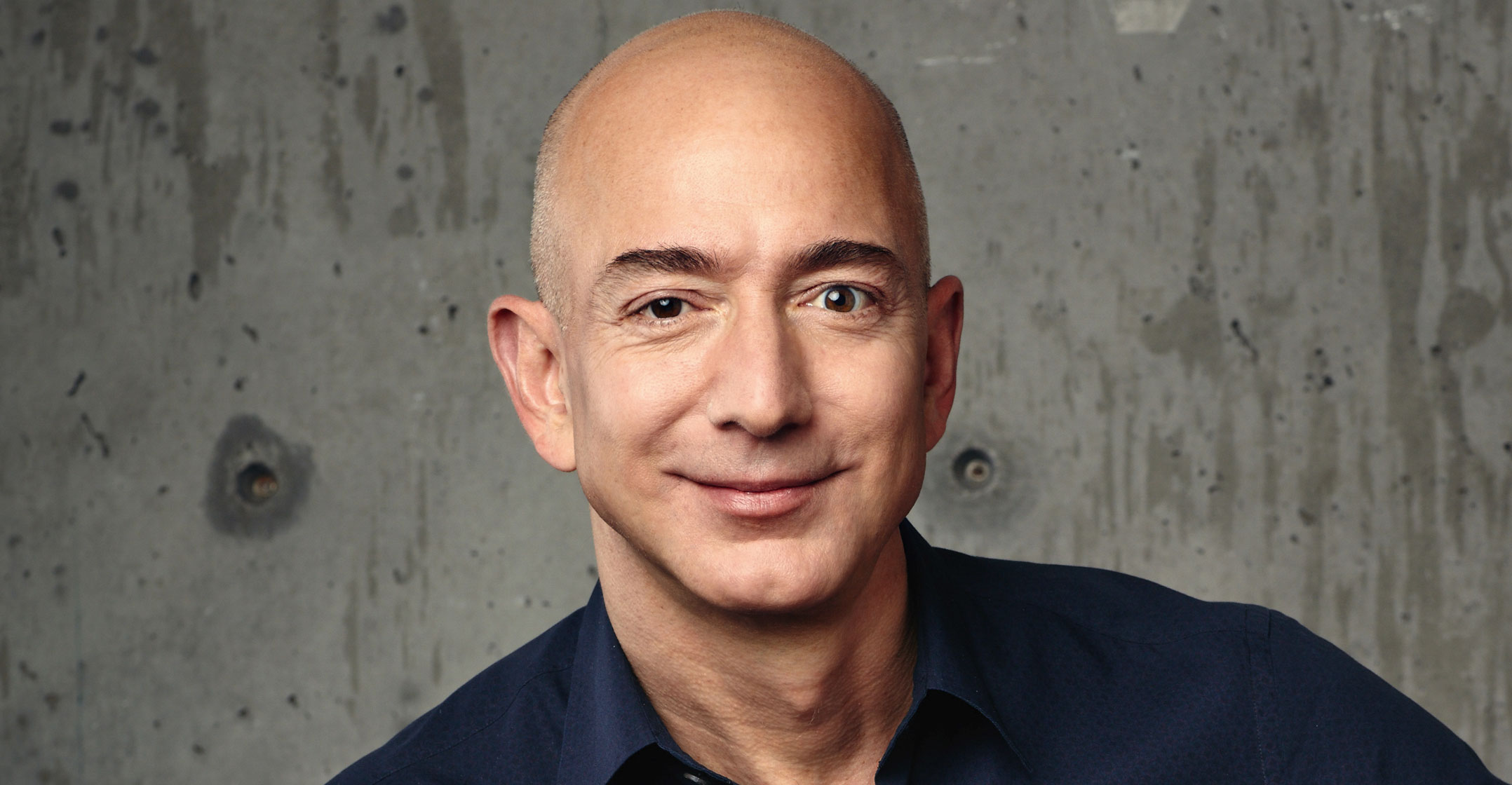

For more than two decades, Jeff Bezos has famously sacrificed profit for growth, persuading Wall Street that Amazon.com was best served pouring money into the logistical nuts and bolts that have turned his company into the Walmart of the Web. More recently, investors have found solace in the company’s profitable cloud services business, which has helped offset losses in e-commerce. Still, for the past five years, Amazon’s average profit margins have languished at about 1%.

Now along comes a business that could generate consistent and healthy returns: it’s called advertising. Over the past several years, Bezos & Co have quietly put together the pieces for a marketing platform that lets Amazon make money from the sheer size of its audience.

Having bet on Amazon cloud services and pushed the shares past US$1 300, investors are now salivating about the ad business, which doesn’t require big investments in new data centres or shipping hubs and generates fat margins. On Monday, BMO Capital Markets upped its Amazon price target to $1 600/share, based largely on the growth of the ad business. Some analysts are predicting Amazon will reach $2 000, making it the first company with a $1 trillion market value.

“Advertising is the most profitable business in the world,” says Jay Kahn, a partner at Light Street Capital, who notes that Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba Group gets more than half its revenue from ads. “For Amazon, advertising is going to be more profitable than its cloud business.”

On Thursday, Amazon once again reminded the world of its growing dominance, revealing a shortlist of North American cities vying to host the company’s second headquarters.

For years, Amazon kept advertising on the site subtle for fear of alienating shoppers who had become used to choosing what to buy based largely on customer reviews and price. Amazon has been slowly giving more prominent placement to sponsored products in search results, forcing brands to buy ads to win top billing. It’s easy to see why. By 2021, advertising on websites and mobile devices will account for half of all ad spending in the US, capturing greater share than television, radio, newspapers and billboards combined, according to EMarketer.

So far, that shift that has mostly benefited Google and Facebook. By contrast, Amazon has a tiny advertising business that last year generated $1.7bn in revenue, according to EMarketer, compared with Google’s $35bn and Facebook’s $17.4bn. But it’s growing quickly because companies like Procter & Gamble and Mondelez see Amazon as the place to win the “digital shelf” in the same way they fought to win the physical shelf in supermarkets.

Platform play

Amazon has an advertising platform no other company can match: a Web store selling hundreds of millions of products combined with a streaming entertainment service and a trove of data about customer preferences. Amazon attracts 180m US visitors each month — all or most with shopping on their mind. And as more people shop on smartphones, they’re skipping search engines like Google for Amazon’s mobile app.

Advertisers are paying attention. Just as big brands pressed their ad agencies a few years ago to devise plans to get the best bang for the ad buck with Google and Facebook, they’re now demanding an “Amazon strategy”. In November, ad giant Omnicom Group set up a specialised operation just to direct ad dollars to e-commerce, particularly Amazon, which has forced consumer brands to re-evaluate marketing decisions. “It’s wreaking havoc on traditional retail models,” says George Manas, president of Omnicom’s Resolution Performance Marketing.

In negotiations with advertisers, Amazon bills itself as a better advertising investment than Google’s search engine and Facebook’s social media platform since people on Amazon are looking to buy, according to three people familiar with the negotiations. Amazon declined to comment.

“Similar to the candy and magazine racks, which are the most valuable space in the store, Amazon is the most valuable space on the Web because you are at the very bottom of the funnel,” says Scott Galloway, a marketing professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business and author of The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. “Not only are people about to make a purchase, but you know what’s in their basket. It’s hard to imagine a more target-rich medium than Amazon or robust offering.”

Amazon advertisements also offer real-time insights into how a marketing campaign is performing, a process that typically takes weeks when using traditional methods like TV commercials or coupons. “You can put a sale on Amazon and see relatively quickly if there’s an uptick,” says Neil Ackerman, a former Amazon and Mondelez executive who leads innovation for Johnson & Johnson’s global supply chain. “Amazon realises it can use this to grow ad revenue and it can charge more because it provides instant results.”

Meanwhile, Amazon is pushing beyond the sponsored search results and display ads that are the bulk of its ad business. The company is more aggressively selling itself as a lifestyle media brand that influences purchasing decisions elsewhere, similar to magazine advertisements or billboards, the people said. It is increasing its investment in a data team tasked with measuring how advertisements on Amazon generate sales beyond Amazon, one of the people said, since that is more difficult to measure than advertisements on Amazon that directly result in sales.

Future advertising products could include buying products within Amazon Video programmes, using the “X-ray” feature that currently lets viewers learn more about a particular actor during a show, according to two people familiar with the matter. And while Amazon maintains it won’t sell advertising on its voice-activated Alexa platform, advertisers are inquiring given the buzz around its Echo digital assistants, two people said.

Money shifting

Big packaged goods companies are signing on. Executives see Amazon as the future way to reach shoppers and are shifting spending from traditional advertising channels to cement their place with Amazon. Even though Amazon has small grocery market share, brands think the next few years are critical because once shoppers establish regular shopping lists online, it will be hard to woo them back. Big grocery brands and manufacturers spend $225m on advertising and in-store promotions each year, with more money shifting to digital advertisements, according to Cadent Consulting Group. Big Food has been mired in a sales slump for years amid changes in how consumers shop and eat; having an Amazon strategy helps them signal to Wall Street they’re keeping pace with the changes.

“Grocery manufacturers and brands are shifting money because they don’t want to lose on Amazon,” says Guru Hariharan, a former Amazon executive and CEO of Boomerang Commerce, which makes software that help brands sell online. “You cannot lose the Amazon battle and hope to survive over the next 10 years.”

Ultimately Amazon could upend the entire advertising industry, although some analysts believe Google will withstand the threat, as it did when Facebook pushed into the market. The ad money going to Amazon isn’t necessarily being redirected from Google. Instead it is dollars once allotted for television or offline retail promotions, according to Resolution Performance Marketing’s Manas, who says: “I’m seeing it come from all sorts of nooks and crannies.” — Reported by Spencer Soper and Mark Bergen, with assistance from Mark Gurman and Craig Giammona, (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP