Founded in 1911, IBM is 100 years old on 16 June. TechCentral senior journalist Craig Wilson traces the rise and fall and rise of Big Blue.

IBM was the result of a merger of four companies, engineered by a prominent financier, Charles Flint. Until 1924, the company traded as the Computer Tabulating Recording (CTR) Corp, one of the four companies that had merged in 1911. As the name suggests, the company’s primary business then was the design and manufacture of punch cards and associated machinery.

Punch cards not only allowed employers to keep a close eye on their staff, and become a workplace stereotype in the process, but they were the first automated method of collecting data.

IBM’s advances in punch cards would lead to more accurate census taking, better inventory keeping during World War 2, and eventually the related developments in automation that would lead to the mainframe and personal computers.

Today, IBM employs more than 400 000 people, its branding is universally recognisable and it continues to hold more patents than any other US-based technology company. IBM has eight research laboratories worldwide, and between them, its employees have earned five Nobel prizes, four Turing awards, five National Medals of Technology, and five National Medals of Science.

Sam Palmisano is the current CEO, but he’s only the most recent in a string of illustrious leaders. Perhaps the most famous was Thomas Watson Sr. Aside from being at the helm for 42 years, he turned the term “THINK” into the company’s mantra-cum-slogan, pioneered the “open-door policy” that saw the value in keeping management approachable, and pioneered the previously unheard of notions of employee benefits like paid leave.

Watson Sr is also credited with initiating the corporate culture and values that IBM continues to profess. Aside from looking after his own employees, Watson also emphasised the importance of corporate social responsibility.

During the Great Depression, rather than downsize, Watson invested heavily in technical development and education, actually growing IBM’s workforce. It was a gamble, but one that paid off. IBM has proved to be a company not averse to large gambles and, as with all gamblers, it hasn’t always won.

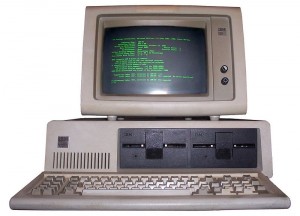

The move from mechanical to electronic means of handling data was a gamble that paid off. By the end of the 1950s, 4 000 of the 6 000 computers in operation in the US were IBM machines.

IBM was the first company to employ a black salesman in 1946, the first with an equal opportunities policy letter in 1953 (a year before Brown vs The Board of Education), the first to offer partner benefits to same-sex couples, and one of the first to self-legislate against corporate racial or sexual discrimination.

On the technical front, IBM has been responsible for a long list of firsts. It built the first Chinese ideographic character typewriter. In 1956, Arthur Samuel of IBM’s Poughkeepsie, New York laboratory programmed an IBM 704 to play checkers and “learn” from the games it played.

By 1964, IBM produced approximately 70% of all computers. Its System/360 products of the same year were the first with interchangeable software and peripherals. Its Selectric typewriters included “memory” and were the forerunners of contemporary word processing and desktop publishing.

IBM’s mainframes ran American Airlines’ reservation system in the first system of its kind first to work over phone lines. IBM invented DRAM, arguably one of the most important aspects of personal computing.

An IBM researcher, Benoit Mandelbrot, discovered fractal geometry. Its systems and people helped Nasa’s first moon landing, for 40 years the company was one of the most prominent sponsors of the Olympic Games, and in 1981 IBM’s PC won Time magazine’s person of the year award.

Some of these successes can be attributed to decisions that must have seemed minor at the time. In 1969, the company split its hardware from its software and services. Before that, hardware had simply been bundled with software. Thus, essentially, IBM created the software industry.

Of course, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing and innovations. IBM has survived antitrust cases, a failed foray into the copier market, and the almost fatal decision to outsource component manufacture to Microsoft and Intel in the early 1980s. IBM also survived the embarrassment of system problems at 1996 Olympic games and the 2001 controversy surrounding Edwin Black’s book that claimed links between the company and the Holocaust.

By 1989, IBM’s earnings had dropped by a third. Four years later, it announced the largest single-year corporate loss in US history of US$8,1bn. IBM had become an overweight dinosaur that couldn’t compete with more agile, smaller companies. Furthermore, it had outsourced the very elements that could have kept it dominant, resulting in the Microsoft megalith.

In 1993, for the first time in its history, IBM hired an outsider to lead it as CEO. His name was Lou Gerstner. He’d been chairman and CEO of RJR Nabisco for four years, and had previously spent 11 years as an executive at American Express. Within a year of his appointment, IBM was back in the black.

Gerstner consolidated various arms of the company that had been split to fend off smaller, niche firms’ competitive advantage of small scale and the quick decision-making that comes with that. IBM’s software strategy also shifted focus to middleware – the vital software that connects operating systems to applications.

More recently, IBM sold its PC division to Lenovo in 2005, and has largely vanished from the realm of personal computing. Arguably, there is a generation of children to whom the once ubiquitous blue logo is now a mystery.

However, 100 years since it started, IBM continues to drive innovation and advancement, but that’s not what’s most impressive about it. What’s most impressive is that it survived, and continues today to thrive.

IBM designed magnetic strips that are now the standard for bankcards, invented the floppy disk and the first portable (albeit 24kg) computer, patented the barcode and created barcode scanners, designed the predecessor of the modern ATM, pioneered computer speech recognition, created the hardware necessary for laser eye surgery, and introduced the TrackPoint cursor control device found in the centre of the iconic ThinkPad’s early keyboards.

IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer famously beat Garry Kasparov at chess and the company coined the term “eBusiness”. Today, IBM-designed chips are used in PlayStation 3, Xbox 360 and Wii game consoles.

IBM also continues to regain ground in supercomputing with high-end machines based on scalable parallel processor technology. Most importantly, IBM continues to persevere and drive competition, even if it’s relinquished many crowns along the way.

To survive 30 years in the fast-moving and cutthroat world of technology is a great achievement. To be able to celebrate a centenary puts IBM in a league of its own. — Craig Wilson, TechCentral

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook