New Zealand’s official privacy watchdog has described Facebook as “morally bankrupt” and suggested his country follow Australia’s lead by making laws that could jail executives over streamed violence such as the Christchurch mosque shootings.

New Zealand’s official privacy watchdog has described Facebook as “morally bankrupt” and suggested his country follow Australia’s lead by making laws that could jail executives over streamed violence such as the Christchurch mosque shootings.

Privacy commissioner John Edwards has been critical of Facebook’s response to a gunman using the platform to live-stream some of the slaughter of 50 worshippers and the wounding of 50 more at two mosques on 15 March.

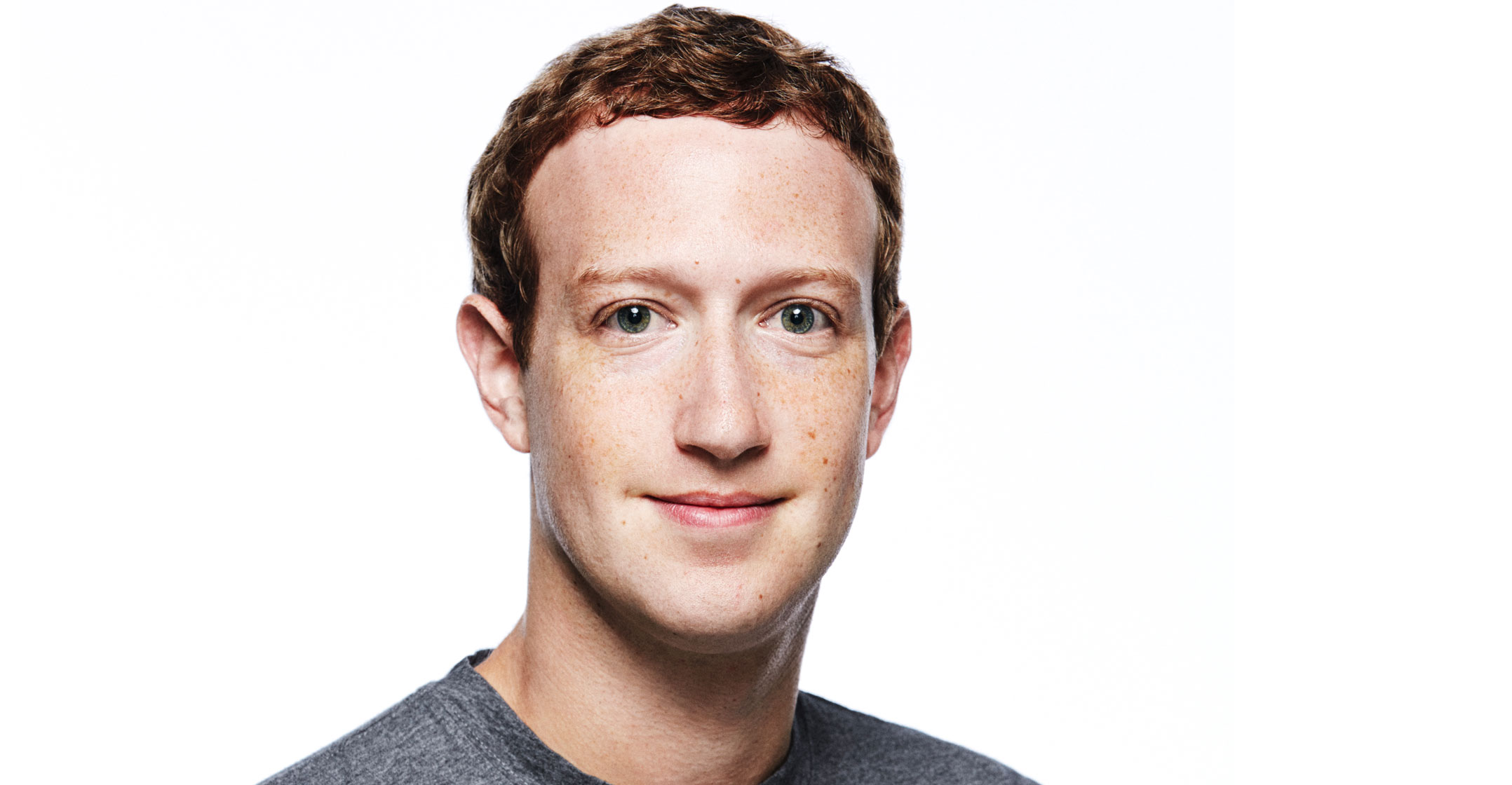

Edwards made his comments after Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently rejected calls to introduce a delay in his live-streaming service Facebook Live, saying it would interfere with the interactivity of live-streaming.

“Facebook cannot be trusted. They are morally bankrupt pathological liars who enable genocide (Myanmar), facilitate foreign undermining of democratic institutions,” Edwards posted on Twitter.

Facebook has been criticised for not doing enough to police hate speech in Burma (Myanmar), where a government campaign against minority Rohingya Muslims has been described by the United Nations as ethnic cleansing.

The platform has also been at the centre of claims that Russia meddled in the 2016 US presidential election.

‘Deeply committed’

Facebook responded to Edwards’ post with a statement that said its chief operating officer, Sheryl Sandberg, had recently shared the policy and technical steps the company was taking to strengthen the rules for using Facebook Live, address hate on Facebook platforms and support the New Zealand community.

“We are deeply committed to strengthening our policies, improving our technology and working with experts to keep Facebook safe,” the statement said.

Edwards, who is tasked with protecting New Zealanders’ personal information according to the country’s Privacy Act, said that governments needed to come together and “force the platforms to find a solution” to the problem of live-streaming of atrocities such as the Christchurch killings, as well as suicides and rapes.

“It may be that regulating, as Australia has done just in the last week, would be a good interim way to get their attention and say, ‘Unless you can demonstrate the safety of these services, you simply can’t use them’,” Edwards told Radio NZ.

“It may be that regulating, as Australia has done just in the last week, would be a good interim way to get their attention and say, ‘Unless you can demonstrate the safety of these services, you simply can’t use them’,” Edwards told Radio NZ.

Edwards regards himself as an advocate for Christchurch victims who had their right to privacy violated by having their deaths broadcast via Facebook to the world in real time.

His office said the privacy commissioner had taken to making his criticism of Facebook about its lack of live-streaming safeguards public “because he has few other options”.

“Under the current Privacy Act, his office has no penalties it can impose on global tech companies like Facebook,” the commissioner’s office said in a statement.

“His only resort is to publicly name Facebook for not ensuring its live-streaming service is a safe platform which does not compound the original harm caused by the Christchurch killings,” the statement added.

The Australian parliament on Thursday passed some of the most restrictive laws about online communication in the democratic world.

It is now a crime in Australia for social media platforms not to quickly remove “abhorrent violent material”.

Prison and fines

The crime would be punishable by three years in prison and a fine of A$10.5-million, or 10% of the platform’s annual turnover, whichever is larger.

The Digital Industry Group — an association representing the digital industry in Australia including Facebook, Google and Twitter — said taking down abhorrent content was a “highly complex problem” that required consultation with a range of experts, which the government had not done.

Australia wants to take its law to a Group of 20 countries forum in Japan as a template for holding social media companies to account.

New Zealand’s justice minister, Andrew Little, said last week his government had also made a commitment to review the role of social media and the obligations of the companies that provide the platforms.

He said he had asked officials to look at the effectiveness of current hate speech laws and whether there were gaps that need to be filled.

Facebook last year disregarded Edwards’ ruling that it had breached the Privacy Act by not releasing information to a New Zealand man who wanted to know what others were saying about him on the social network.

Facebook argued that it was not bound by New Zealand’s Privacy Act because it was based overseas, but later agreed to comply with the local law.

New Zealand’s parliament is amending the act to give the privacy commissioner more powers and to clarify that offshore companies that hold information about New Zealanders must comply with the legislation.