Facebook shares fell the most in two months on Monday as American and European officials demanded answers to reports that a political advertising firm retained information on millions of Facebook users without their consent.

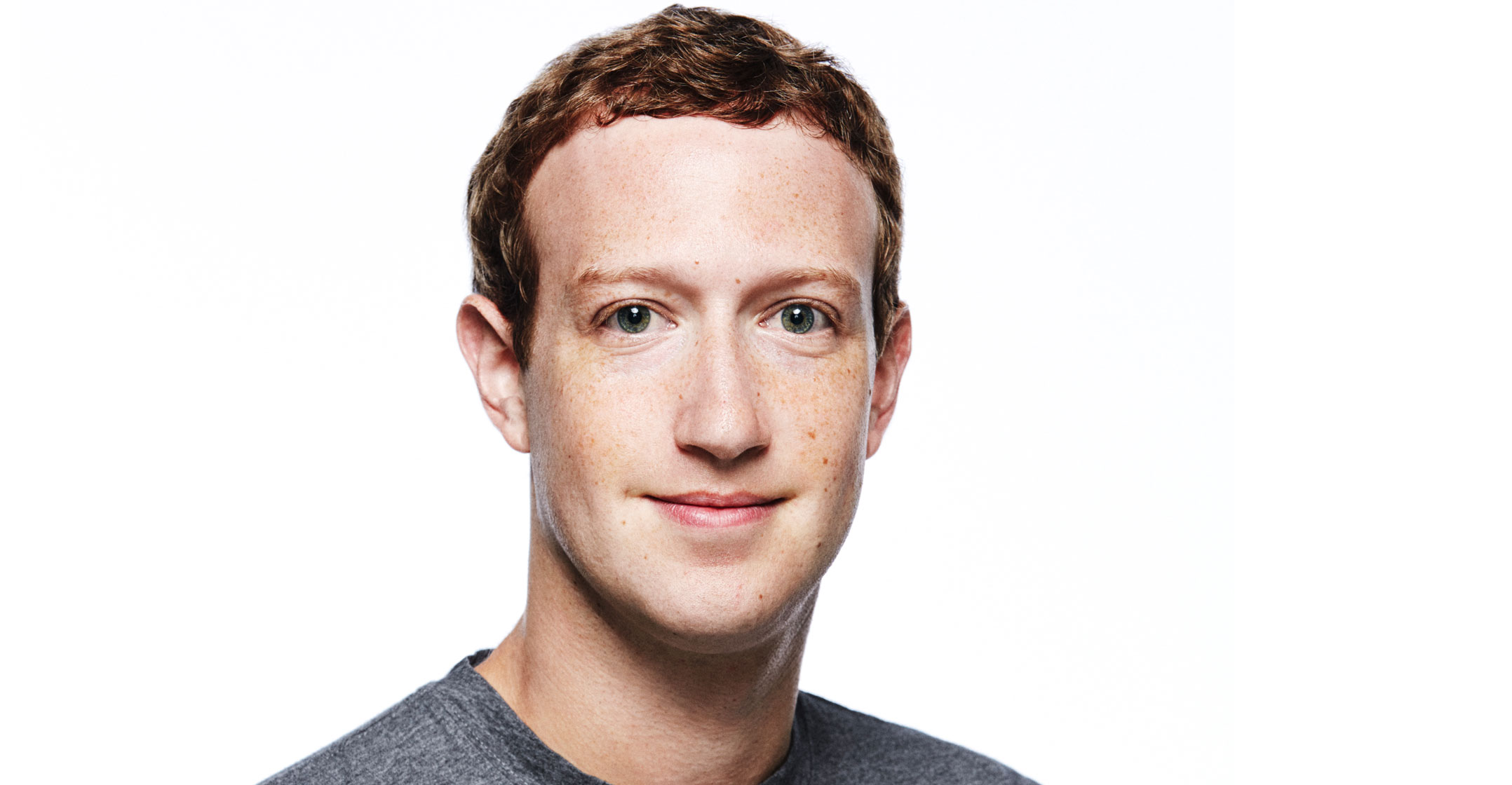

Politicians on both sides of the Atlantic are calling on CEO Mark Zuckerberg to appear before lawmakers to explain how UK-based Cambridge Analytica, the advertising-data firm that helped Donald Trump win the US presidency, was able to harvest the personal data.

Facebook has already testified about how its platform was used by Russian propagandists ahead of the 2016 election, but the company never put Zuckerberg himself in the spotlight with government leaders. The pressure may also foreshadow tougher regulation for the social network.

A top UK lawmaker on Monday backed sweeping new powers for the nation’s privacy watchdog.

“The time has now come for us to look at giving more powers to the information commission in the UK,” Damian Collins, a Conservative and chair of the UK digital, culture, media & sports committee, told LBC radio in an interview on Monday.

Facebook on Friday said that a professor used Facebook’s login tools to get people to sign up for what he claimed was a personality analysis app he had designed for academic purposes. To take the quiz, 270 000 people gave the app permission to access data via Facebook on themselves and their friends, exposing a network of 50m people, according to the New York Times. That kind of access was allowed per Facebook’s rules at the time. Afterward, the professor violated Facebook’s terms when he passed along that data to Cambridge Analytica.

Facebook fell as much as 5.2% to US$175.41 on Monday in New York, wiping out all of the year’s gains so far. It was the biggest intraday drop since 12 January.

Facebook found out about the breach in 2015, shut down the professor’s access and asked Cambridge Analytica to certify that it had deleted the user data. Yet the social network on Friday suspended Cambridge from its system, explaining that it had learnt the information wasn’t erased. Cambridge, originally funded by conservative political donor Robert Mercer, on Saturday denied that it still had access to the user data, and said it was working with Facebook on a solution.

Criticism

A researcher who worked with the professor on the app is now currently an employee at Facebook, which is reviewing whether he knew about the data leak.

The denials and refutations did little to ease the criticism. Damian Collins, a British lawmaker, said on Sunday that Zuckerberg or another senior executive should appear in front of his committee because previous witnesses have avoided difficult questions, creating “a false reassurance that Facebook’s stated policies are always robust and effectively policed”. He added in an interview on British radio on Monday that Zuckerberg should “stop hiding behind his Facebook page and actually come out and answer questions about his company”.

The next few weeks represent a critical time for Facebook to reassure users and regulators about its content standards and platform security, to prevent rules that could impact its main advertising business, according to Daniel Ives, an analyst at GBH Insights.

“Changes to their business model around advertising and news feeds/content could be in store over the next 12-18 months,” Ives wrote in a note to investors.

Facebook, meanwhile, has sought to explain that the mishandling of user data was out of its hands and doesn’t constitute a “breach” — a definition that would require the company to alert users about whether their information was taken, per US Federal Trade Commission rules.

Menlo Park, California-based Facebook no longer allows app developers to ask for access to data on users’ friends. But the improper handling of the data raises systemic questions about how much companies can be trusted to protect personal information, said Nuala O’Connor, president and CEO of the Center for Democracy & Technology.

“While the misuse of data is not new, what we now see is how seemingly insignificant information about individuals can be used to decide what information they see and influence viewpoints in profound ways,” O’Connor said in a statement. “Communications technologies have become an essential part of our daily lives, but if we are unable to have control of our data, these technologies control us. For our democracy to thrive, this cannot continue.” — (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP