At the Frankfurt Auto Show next month, Lamborghini will unveil a hybrid version of the Aventador. The Bologna, Italy-based brand will make 63 of them, all already spoken for.

At the Frankfurt Auto Show next month, Lamborghini will unveil a hybrid version of the Aventador. The Bologna, Italy-based brand will make 63 of them, all already spoken for.

That is the rumour, at least. Lamborghini has declined to comment on any plans to debut an electric-motor supercar, though it has hinted at it publicly in recent months and described in past detail how such special projects form an integral part of the business.

“The Reventon prompted the big discussion about the dimensions of this segment,” Maurizio Reggiani, Lamborgini’s chief engineer, told Bloomberg Pursuits during an interview in his office at company headquarters, noting that Lamborghini “started” the segment with its Lamborghini Reventon in 2007.

“We were the first to do it like this. As we scouted more and more during that time, we started to see how, in this market, you can stretch in terms of price and in terms of demand. The Reventon coupe was US$3-million; the Reventon roadster was $3.2-million; the Centenario was $2-million. So in this segment, we know there is a marvelous market.”

The mid-engine V12, all-wheel-drive Reventon famously hit 354km/h on a test in Dubai, an astounding figure for a production car at that time. Only 20 were made, plus one marked for the Lamborghini museum.

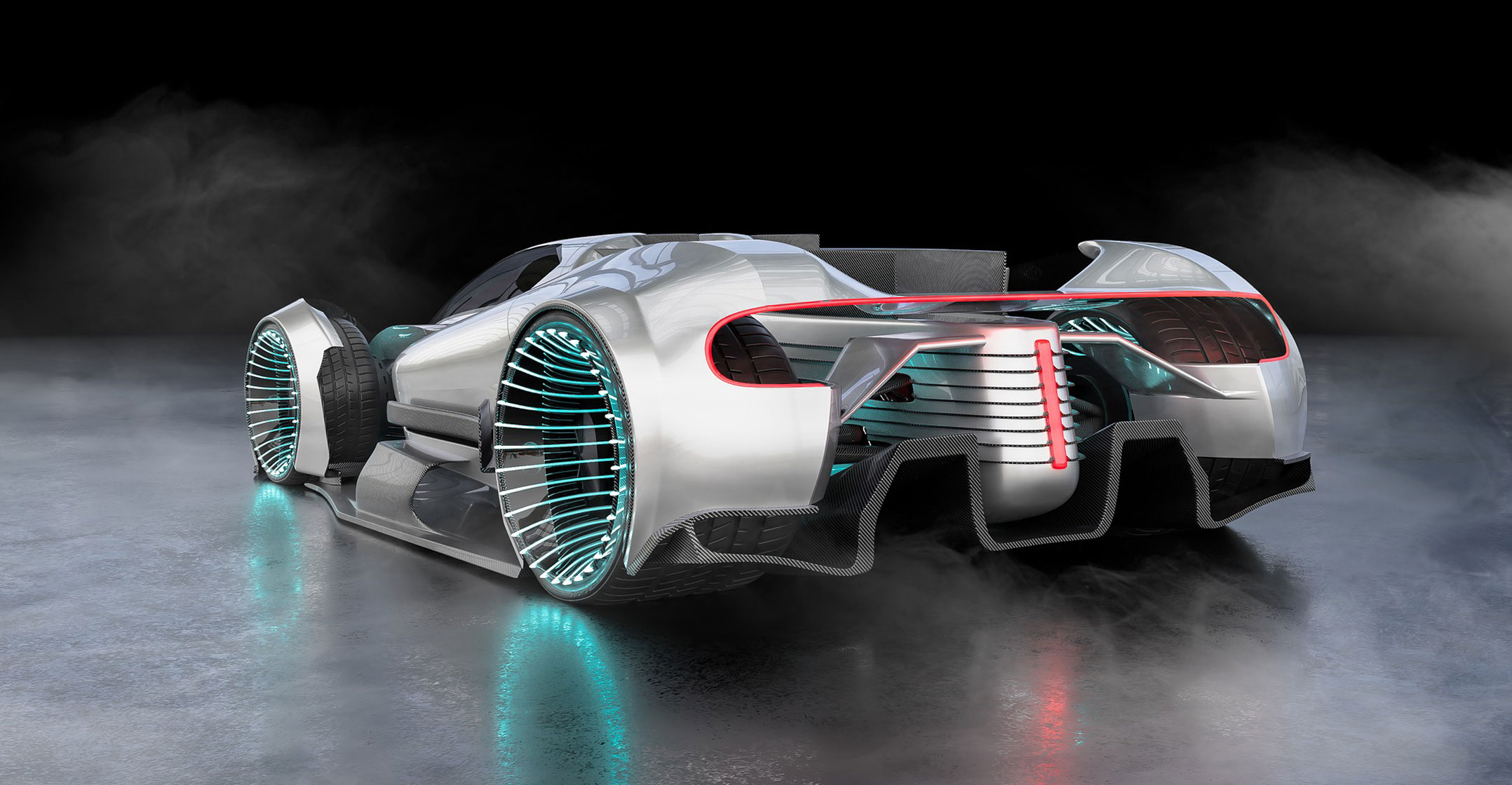

Should it happen, the new hybrid will join a burgeoning field of extremely limited-edition hybrid and electric supercars from such luxury powerhouses as Aston Martin, Ferrari, Koenigsegg, Lotus, Mercedes-Benz and Pininfarina. They have been flaunted recently in dazzling hues on golf courses and during private parties at seaside villas, heralded on Instagram fanboy accounts and Rodeo Drive parades orchestrated for YouTube.

In spades

Where it used to be that a company would have only one ever, or at most, one per year, now it seems they’re whipping them up as fast as possible. In the past year, Aston Martin alone has debuted and promised supercars in spades: the super-lightweight 1 160-horsepower Valkyrie and the 986hp Valhalla hybrids, plus a Vanquish Vision concept and Valkyrie AMR Pro concept, not to mention the electric offerings from its Lagonda department. They follow the precedent from the One-77 and Vulcan supercars that came in the years before. It’s quite a different mood for what used to be a staid, small automaker tucked into the verdant hills of England’s Cotswolds region.

Many supercars, such as the $2.72-million Mercedes-AMG Project One limited-to-275 hybrid supercar based on Mercedes’s Formula 1 car, are sold as concepts, or very rough prototypes, and require six- or seven-figure deposits years in advance to ensure delivery. Others are sold with even less — a few sketches, a rendering, a foam-filled shell at an auto show. That’s if you can even get on the list to buy one. The official party line for most, like the Lambo, is that they have sold out before they’re even seen.

Some collectors are starting to find the rigmarole rather tedious.

“We need an awakening and cleansing soon to get everyone back into reality,” says Dan Kang, the well-known car collector based in southern California, who owns a McLaren Senna, a Guntherwerks Porsche 911, and Lamborghini Centenario in similar carbon-fibre livery, among other supercars. “It’s not even the new companies, but the current heritage brands as well, who feel they can demand the new price points without much substance. They need to support what they have already sold — not what car they can shovel up next.”

When manufacturers are unveiling cars that can’t be driven for years to come, and the very people able to afford them are over the hype anyway, it raises the question: have we reached peak supercar?

Modern supercars, and their higher-end cousins, hypercars — both relative terms defined largely by who you ask — are latecomers to the thread of automotive history. First, there were the rockets of their time, such as the Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrows of the 1930s and 300SL Gullwings of the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Ferrari 250 GTOs dominated countless races and reached automotive immortality as the ultimate auction house blue-chip buys. But the supercar as we know it really came into its own in the late 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, when hedonism reigned supreme. Such early examples as the Lamborghini Countach and Ferrari F40 set major precedents for design and performance. They were like space ships compared to the mundane and affordable metal boxes of the day. Everyone has a favourite; just ask the guys down at the weekend coffee klatch about the Vector, the Ferrari Enzo or the Porsche Carrera GT. You’ll get a reaction.

They were duly expensive. A Countach sold for $72 000 at the time, or the equivalent of $375 000 today; the F40 cost $400 000, or the equivalent of $884 000 today.

Age well

Supercars tend to age well if you have the patience, luck and financing to get your hands on one. On 16 August in Monterey, California, a 1994 McLaren F1 sold for $19.8-million, obliterating the previous high-price paid for a McLaren: $13.75-million in 2015. (Its original MSRP was around $1-million.) You won’t be surprised to learn that the man who designed that car, Gordon Murray, is now designing a round of 100 new supercars tentatively called the T50 and priced near $3-million.

The role of the supercar used to be to act as the halo for the brand, to attract media attention and consumer hype to a marque. Even if only a few people could afford to actually buy the exciting, sexy car, they’d know about the brand because of it and then buy something more affordable. Automakers figured that if you loved, or at least knew about, the Acura NSX that Formula 1 champion Aryton Senna helped develop, you’d be more likely to buy an Accord. It seems a stretch — but the basic awareness of a brand is half the battle, marketers say. And an NSX is a lot more likely to grab headlines than an Accord is.

Supercars also carried the advanced driving technologies consumers could expect to see seep into the rest of the product line-up in succeeding years. The SF90 Stradale that Ferrari debuted in May is the first plug-in hybrid in Ferrari’s history, while its 679hp twin-turbocharged 4l V8 is also the first time a V8 has ever been under a Ferrari bonnet. Its petrol engine and trio of electric motors combined make it the most powerful Ferrari ever, totaling 968hp.

In fact, the SF90 is the latest in an onslaught of supercars that has taken a slightly different tone.

Supercars are increasingly electric, rather than powered by the galloping V12 and W16 engines of old. The Aston Martin Valkyrie, Koenigsegg Jesko, Lotus Evija, Mercedes-Benz Project One and Pininfarina Battista, among others, all use electric motors to help boost them to ever-higher (at least in theory) feats of speed and strength. They all have yet to hit the market in production form.

They’re coming from all sides of the market, too: such big, old heritage brands as Lamborghini and Ferrari, of course, but also from namesake novelty brands such as Gordon Murray Automotive and just-minted start-ups dotting the US, Europe, the Middle East, Korea, Japan and China. These boutiques tend to have obscure names and opaque origins, blending the lines among automotive companies, tech companies and software start-ups. Witness the British Dendrobium D1 and Ariel P40, the Chinese XING Mobility Miss E, the Croatian Rimac Concept_One and the Japanese Aspark Owl. They come and go in the automotive consciousness, many making a splash at a car show with a foam mould or rendering, trotting that same car around for a year or two, then quietly merging with a larger auto or tech company, or shutting down altogether.

Rather than loss-leaders for the brand, they’re now a big part of the business model — or the business model.

‘Seed money’

“Basically, (the deposits to the supercar start-ups are) seed money to get operations up and running — applied to the cost of the car,” says Kevin Tynan, senior automotive analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “Think of it as venture capital, with the return being a supercar instead of a percentage.”

In November, Lamborghini announced the one-off Lamborghini SC18 Alston, created for a single customer at a multimillion-dollar cost.

It was a strategy that took cues from the Lamborghini Reventon: when it debuted, its almost immediate sell-out success of all 20 models to Middle Eastern sheiks and Russian billionaires proved to Lamborghini brass that the market could handle the extravagant price and exclusivity of vehicles heretofore considered too wild for it to bear. This paved the way for the $4.5-million Veneno and the aforementioned, 759hp Centenario, rare-as-plutonium supercars that came several years later.

Reggiani characterised the one-offs as a not-insignificant part of Lamborghini’s bottom line, though he declined to give a percentage.

Elsewhere, Ferrari, which announced a Special Projects Division 10 years ago, has built one-off cars such as the Superamerica 45 and the P540 Superfast Aperta. Aston Martin has quietly made such one-offs as the CC100 and Valkyrie hybrid; McLaren made the 1 035hp hybrid Speedtail.

“The sky is the limit,” Bugatti chief Stephan Winkelmann said this summer at the Villa d’Este Concours d’Elegance. The company had just unveiled the La Voiture Noir car purchased by Ferdinand Piëch, the notorious Volksagen boss who died on 25 August. The car cost nearly $19-million, after taxes and fees.

Proponents, and corporate press materials, rave about the shocking designs and extensive technologies of these extreme supercars, but their proliferation has simultaneously spurred the customary cadre of critics. Those sceptics — or, maybe, prophets — point to a whole lot of empty promises from the automakers and question their connection to reality, whether now or later.

There’s no question that in the future the world is going to have to change. Consumers will have to find sustainable transportation, says Jim Glickenhaus, who makes road-legal hypercars and supercars of his own. But he notes that his wife’s Tesla S is already much faster than she could ever drive it on public roads, both legally and logistically.

“Where are you going to drive a 2 000hp electric supercar? You’ll run out of road,” he says. “I already get a headache in the Tesla! And now we’re getting 2 000hp hyper-electric cars? Seriously. Why you would ever need a 2 000hp electric hypercar? I just don’t understand. You’re never going to drive a hypercar to pick up groceries.”

Very small market

Not that any of the people who currently own the few electric hypercars that have actually come to market ever go grocery shopping; the idea is that there is a finite and very small market for that type of car at all, and we are near reaching the saturation point. Call it hypercar fatigue, contagious only among those who have been buying the hypercars in the first place.

Many of the new supercars are not legal to bring into the US under normal permitting, anyway. They’re legal only to “show and display,” not to drive on public roads, because they don’t meet federal safety and emissions regulations. The Ferrari Icona Series Monza SP1 and SP2 cars, for instance, are legal for track use only.

Not that it matters. Follow Kang on Instagram or Mattress King collector Michael Fux for any length of time, and you’ll see they drive their more practical Porsches and Rolls-Royces more than the hypercars they hoard. (Fux recently pulled up to Manhattan’s Cipriani restaurant in his white Rolls, for instance, rather than his green Senna.) Peruse the auction catalogues of any major sale, browse through the feed of wealthy YouTube go-getters or ask the young scions of Saudi families: they’re all bragging about how few miles their supercar has on the odometer, not about the great drive they took up the coast, say.

The popular thing for younger, newer collectors seems to be not driving your car, instead of driving it — a drastic change from the longstanding tradition of the best, most hallowed cars earning their stripes by taking epic drives, winning adventure races and parading through Paris.

“This whole modern supercar-hypercar market is destined to collapse under its own weight and implode on itself,” says Winston Goodfellow, an automotive author and analyst who judged the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance last month. “After all, if the things aren’t being utilised for their original purpose, there are only so many suckers and cult members out there who will agree that this weird Kool Aid actually tastes good and makes sense to drink.”

There are other cracks in the proverbial armour. Mercedes-AMG has yet to deliver any of the Project One cars it promised nearly three years ago. (Deliveries are set for 2021, according to a Mercedes spokesman.) So does Ariel, with the P40 it announced in 2017; Aspark, with the undelivered Owls it announced in 2018; and XING, with the Miss R it announced in 2017. Dendrobium, which announced the D1 last year and has said it would be ready by 2022, is already pointing to Brexit as a reason why it may not be able to deliver on its promises.

“So many investors have said to us that they’re keen but need some resolution one way or another,” Dendrobium boss Nigel Gordon-Stewart told Top Gear.

Indeed. Read through the fine lines of press releases about the new supercars and you’ll see phrases like “working toward being fully funded” and “working to develop a technology partner”, verbal cues that the company is far from anywhere near being able to make production cars. Faraday Future unveiled an electric hypercar concept called the FFZERO1 in 2016 without even having a factory — or the money to build one. It has yet to produce any cars.

Values slumping

Then there’s the fact that the values of the first supercars are slumping. The McLaren F1 that sold in Monterey set a record — but failed to match even the low end of its estimated value before the sale. At the Gooding & Co auctions in Arizona earlier this year, a 1990 Countach failed to reach even its low value estimate of $275 000; so did a Ferrari Testarossa listed for $250 000-$300 000 that sold for (just) $221 200.

The automakers themselves remain notoriously cagey about exactly how supercar sales have been faring. Many blast instant- or near-immediate sell-out numbers in press releases, while others — when asked privately and perhaps more transparently — say that roughly half sold very early, and the rest are expected to sell in the coming weeks. Bugatti, one of the more forthcoming of the lot, has said that this applies to its Centodieci. It famously had to sell only one of the La Voiture Noire cars, anyway the one that went to Piech.

It’s telling, if anecdotal, that public sentiment may be shifting. Locals near one of the biggest annual supercar gatherings in the world — on Cannery Row in Monterrey during car week — even succeeded in getting it cancelled this year amid complaints of noise and general disruption. Please don’t “hoon” around in your Lamborghini, one Instagram user requested.

It was a blow to the automotive “influencers” who are the prime targets for the hypercars — to their egos, at least. After all, if you can’t show off your supercar on social media, is it even really yours, bro?

“The pendulum has already started to swing. It’s just that people don’t notice it because all these manufacturers are flooding the market with new product and obfuscating the view,” says Goodfellow. “When you have companies selling things that can’t even be driven on the street — and no one thinks this is weird — there is real distortion.” — Reported by Hannah Elliott, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP